Garden State Sorcerer

In his new memoir, Springsteen reveals his inner life but is strangely silent on his music

Born to Run by Bruce Springsteen; Simon & Schuster, 510 pp., $32.50

The several dozen rock memoirs on my shelf range from Aerosmith to Jay-Z. Included among them are well-known literary works—Woody Guthrie’s Bound for Glory, Bob Dylan’s Chronicles, and Keith Richards’s Life—as well as numerous ghostwritten volumes that are little more than career summaries with some sex and scandal thrown in. Bruce Springsteen is nothing if not a writer, and his new memoir is sure to find its place in the pantheon of rock literature. He has previously examined his work in Songs (2001), and his lyrics have inspired novelists (see, for example, Bobbie Ann Mason’s In Country). In Born to Run, which took him seven years to complete, Springsteen, now 67, reflects on a life that has been listened to, focused upon, and written about since he was 23.

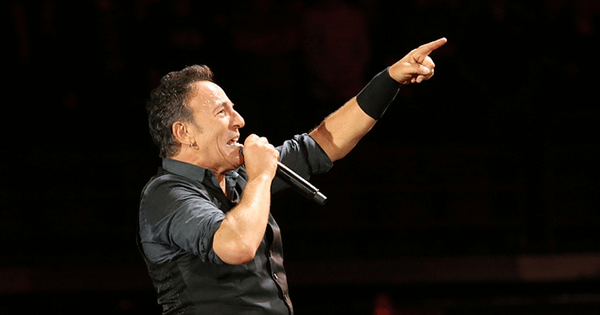

Springsteen is a rock ’n’ roll magician who mesmerizes audiences with long shows that leave them wondering how he does it. His songs have the power to levitate. One of his albums is even titled Magic. But like any great conjurer, he relies on misdirection, drawing attention not to how the tricks are done but to the man performing them on stage—in Springsteen’s case, a poor, working-class kid from Freehold (he had no heat in his bedroom), who was shaped by an abusive father, loving mother, and Catholic school education that left scars. From the start, music offered escape and salvation. He devoted himself to playing and performing, letting nothing impede his way, not his parents’ decision to leave Freehold for California when he was 19, not the difficulty of earning rent money and having to sleep at night on the beach, not the odds against making it, stacked higher than the wall of amps at the Upstage Club in Asbury Park where he played until dawn and met some of the E Street Band members who are still with him today.

Springsteen grants us extraordinary access to his inner life, revealing, for example, that he has seen a psychiatrist for more than 30 years and takes antidepressants. Mental illness runs in the family, his father having been diagnosed late in life as a paranoid schizophrenic. At some point during the phenomenal success of his 1984 album Born in the U.S.A., “the defenses I built to withstand the stress of my childhood, to save what I had of myself, outlived their usefulness.” In therapy, Springsteen came to understand that his relentless ambition and perfectionism had become substitutes for enjoying life. He had found wealth and fame, but not happiness. The results of the work he did with his psychiatrist, he tells us, “are at the heart of this book.” Still, the struggle remains; on several occasions since turning 60 he has fallen into severe depression and agitated anxiety.

Unfortunately, with so much attention being paid to the struggles of the artist, the art disappears. We learn far too little about the work itself: how he creates it and how his music has changed. When he turned in his first record, Clive Davis of Columbia said he needed a hit that could be played on the radio. “I went to the beach and wrote ‘Spirit in the Night,’” is all Springsteen says. And when producer Jon Landau thought Springsteen needed another song for his seventh album, he spent an evening composing “Dancing in the Dark.” Springsteen acknowledges having writer’s block at times, admits to us that he does not know how to read music, and insists he is not “a natural genius.” So how, then, has he done it?

Springsteen also seems uninterested in addressing his political awakening. He mentions only in passing playing at President Obama’s inauguration and ignores completely his campaigning for John Kerry and Vote for Change, the series of concerts he staged in 2004 to encourage young people to turn out on election day. While he discusses Ronald Reagan’s misidentification of “Born in the U.S.A.” as celebratory, and the surprising reaction to his song about the 1999 police shooting of Amadou Diallo, “American Skin (41 Shots),” he resists probing in depth what he has said elsewhere: “I have spent my life judging the distance between American reality and the American dream.”

Springsteen’s education likewise remains a mystery. How did this working-class kid who hated Catholic school, squeaked through high school, and dropped out of community college, and whose house was devoid of books, start devouring and deeply analyzing literature and film? Springsteen’s education may have begun with Elvis Presley and Bob Dylan, but it continued with Flannery O’Connor, John Steinbeck, John Ford, and Terrence Malick, all of whom he credits in the book, along with Willy Loman and Starbuck from Moby-Dick. He has little to say, however, about what led him down these cultural paths.

“The magician should not observe his trick too closely,” Springsteen writes, and so Born to Run is the story of the magician, not the trick, delivered with blistering honesty. He describes himself as controlling and single-minded, a perfectionist with a “huge ego” who runs his band as a “benevolent dictatorship.” He is undoubtedly the Boss, a nickname he chooses not to explain. “I needed disciples,” he confesses, and alludes to, but does not elaborate upon, his struggles with some of his closest collaborators.

Born to Run is ultimately a story about love, learning how to love and be loved, how to forgive and be forgiven. But if by reading this book you think you will discover how he has sustained his career for more than 40 years and entered the pantheon of legends, how his songs have served as the soundtrack for the lives of millions of fans worldwide, and how he continues to deliver shows that transcend time and place and lift audiences into feelings of life everlasting, you will be disappointed. That is a trick even Bruce Springsteen seems unable to explain.