In 1563 Michel de Montaigne wrote a long letter recounting the death of his best friend, Etienne de La Boétie—which he had witnessed from La Boétie’s bedside. After describing his friend’s nobly stoical behavior, the very exemplar of a “good death,” he noted this strange turn toward the end:

After his wife had gone, he said to me: “My brother, stay close to me, please.” And then, feeling either the pangs of death sharper and more pressing, or the force of some hot medicine that they had made him swallow, he spoke in a loud and stronger voice, and tossed in his bed with the greatest violence; so that all the company began to have some hope, for until then it was weakness alone that had made us fear to lose him. Then, among other things, he began to entreat me again and again with genuine affection to give him a place; so that I was afraid that his judgment was shaken. Even when I had remonstrated with him very gently that he was letting the illness carry him away and that these were not the words of a man in his sound mind, he did not give in at first and repeated more strongly: “My brother, my brother, do you refuse me a place?” This until he forced me to convince him that since he was breathing and speaking and had a body, consequently he had his place. “True, true,” he answered me then, “I have one, but it is not the one I need; and then when all is said, I have no being left.” “God will give you a better one very soon,” said I. “Would that I were there already,” he replied. “For three days now I have been straining to leave.” Shortly after, he breathed his last.

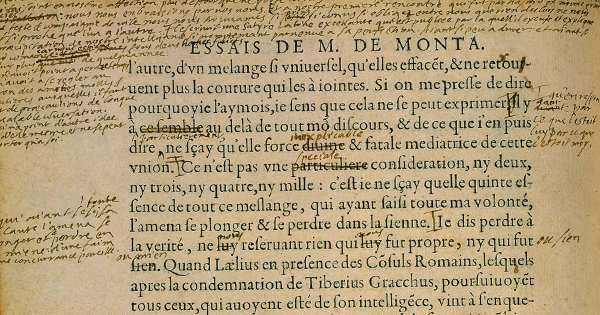

What are we to make of this dying plea to give him a place? More important, what did Montaigne make of it? Some commentators, like Alexander Nehamas in his book On Friendship, have argued that the collection of essays Montaigne began writing a decade later, which ensured his lasting fame, became the very “place” he hit upon to honor that request:

The Essays represent the kind of communication Montaigne might have had with La Boétie, regaling him with the sort of stories, incidents, and thoughts that one would share with one’s close friends—stories, feelings, and thoughts that range from the most trivial and mundane to the most serious and profound and that, in the process, express their author’s personality. But La Boétie was dead; each of the Essays’ readers assumes his role as the friend to whom Montaigne reveals himself. And in order to communicate the central place that La Boétie held in his life, Montaigne located his essay on friendship, whose hero is La Boétie, in the center of the first volume of the essays. Since what was to become the first volume was all he was planning to write at the time, the essay would have been the centerpiece of the whole book, and the Essays would have revolved around it. In addition, Montaigne also included in the essay the text of La Boétie’s political treatise, On Voluntary Solitude.

However, Montaigne subsequently decided to scrap his friend’s thesis, fearing that it was too controversial, and went on to write two more volumes of essays, thus relegating La Boétie to a much more peripheral place in the greater scheme.

I thought about La Boétie’s urgent entreaty the other day when I was sitting in the synagogue during Rosh Hashanah services. Several of the prayers contained the insistent plea to “inscribe us in the Book of Life.” Since Rosh Hashanah is the Jewish New Year, it made sense that one would ask the Deity permission to re-up for another 12 months. One was, in effect, asking like La Boétie for a place in a book. It came to me with a mild flush of shame that in my own life I had replaced the Torah with Montaigne’s Essays as the defining inspirational text.

My daughter used to ask me: “Why do you even go to the synagogue when you don’t believe in God?” True enough, I did not, probably from the time I was 13, but I hoped that there might still be room, or a place, in my birth-religion for atheists, skeptics, and agnostics such as myself. I went for the music and to revive nostalgic memories of my youth in a Hebrew choir. More recently, my daughter asked me: “We’re culturally Jewish, right, Daddy?” Her question pained me, since I would like to believe that there is more to my attachment to Judaism than matzo ball soup, Jackie Mason jokes, and Fiddler on the Roof revivals. What does that “more” consist of, exactly? I asked myself. Is it at all theological in nature? All I could come up with was a warm feeling toward the bookish, exegetical rabbinical tradition, and toward certain ethical principles, such as Judaism’s emphasis on social justice and generosity. I studiously swerved away from considering Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, saving that painful subject for another day. In the meantime, I was lulled into peace and repose by listening to the service in Hebrew, a language I could not understand, which therefore gave me more opportunity to remain in a dreamlike meditative space. Indeed, as I sat there, I started writing this very blog in my head.

Was Montaigne himself part Jewish? Some have found Jewish blood on his mother’s side. If so, that might go a small way toward resolving the guilt of my defection.