Gone Fishin’

Could two famous rivermen really have met their end while grappling giant fish in a Kansas river?

The monster cats are still down there.

In late 2021, repair work on the dam in Lawrence, Kansas, forced Bowersock Hydropower to drain part of the Kansas River to its bed, exposing deep scour holes and the enormous catfish that were nesting in them. For a few days, the company’s Instagram page was full of catfish relocation photos: gloved, gumbooted pairs of people carrying massive flatheads and blue cats overland like furniture and depositing them downstream. The following spring, a new round of photos showcased the open-ended culverts that were being installed to replicate the big cats’ habitat. “We hope this helps maintain the legendary status of Abe and Jake’s honey hole,” one caption announced.

In Lawrence, Abe Burns and Jake Washington need no introduction, although they haven’t been seen around town for a century. They belong to a bygone, largely Black community of fishermen who made their living off the Kansas River—known regionally as the Kaw. And they’ve come to represent that community, thanks to a famous photograph from 1896 in which they proudly flank a pair of 100-pound blue cats, freshly caught. At Abe & Jake’s Landing, a popular event space overlooking the river in downtown Lawrence, there’s a life-size bronze sculpture of the two men and their trophy fish.

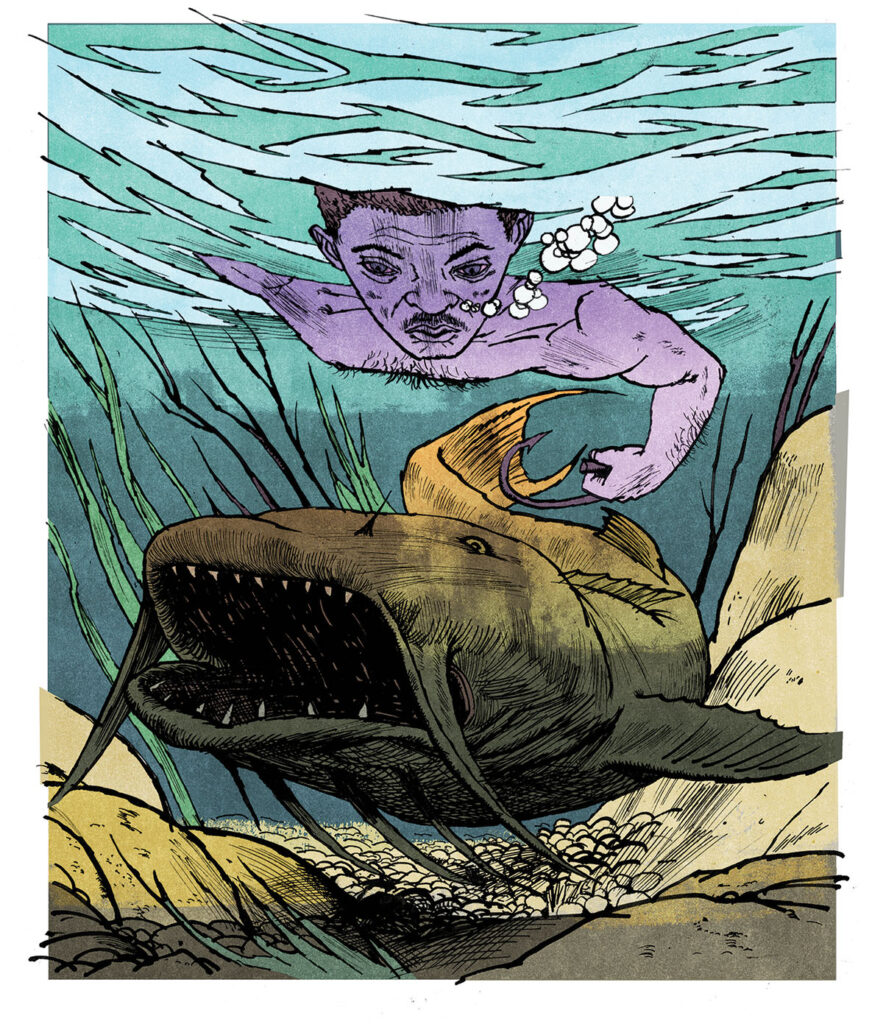

Commercial fishing on the Kaw was a viable profession not only because of the size and abundance of the fish but also because of the now-illegal methods used to harvest them: Abe and Jake were both known to drag giant nets, sometimes trapping 300 pounds’ worth of carp, buffalo, and catfish in a single outing. More daringly, they would dive for their quarry: They’d swim to the base of the dam, or under the wooden floor of an old flour mill, feel around for a big cat, snag it with a gaff hook, and wrestle it to the surface. One summer day in 1902, according to the Lawrence Weekly World, Abe hauled in catfish of 35, 60, and 104 pounds “by diving and stabbing them.”

If that sounds life-endangering, it was. Around Lawrence, it’s generally been understood that either Abe or Jake (or maybe both) died that way—drowned in pursuit of a bewhiskered leviathan. I’ve been hearing versions of this tale for years. Some folks say that the drowned man was never seen again; others, that he washed up on a sandbar downriver, still locked in a death embrace with the big one that didn’t get away. Fascinated by this story and bemused by its fishiness, I decided to take my own deep dive.

As far as I can tell, the legend first appeared in print in a 1973 edition of the Kansas City Star. Phil Ernst Sr., owner of a multigenerational family hardware store in downtown Lawrence, was asked to share local fish stories with writer David Dary. Ernst told of how “Abe Burns … attached the grab-hook to his wrist, waded into the river and went under the mill … but he never came up. No one knows what happened to him, but according to the oldtimers, Burns apparently hooked a big cat he couldn’t handle.” Dary repeated the story in his book Seeking Pleasure in the Old West in 1995. That same year, a museum exhibition at the University of Kansas on regional fishing history featured the iconic Abe and Jake photo. According to its caption, it was Jake Washington who had drowned while diving for catfish with a gaff hook strapped to his arm. The source of that information was probably Tom Burns (no relation to Abe), one of the last commercial fishermen on the Kaw, who had provided stories and artifacts for the show. Burkhard Bilger twice quoted Burns telling the same tale, once in a 1997 article in The Atlantic Monthly and again in his 2000 book Noodling for Flatheads: Jake had “hooked him a giant fish and couldn’t get loose,” Burns told Bilger. “They found them side by side on a sandbar.”

Since the 1990s, the description of side-by-side bodies has resurfaced in almost every version of the story, completing its perhaps inevitable transformation into the Moby-Dick of Douglas County. In 2007, Waterkeeper magazine reported that Abe and the fish were “found downstream—still hooked together.” By 2014, it was once again Jake who had been dragged to his death, and the fish had acquired some serious dimension: “They found his body washed ashore a short time later,” Chad Lawhorn wrote in the Journal-World. “Attached to his hook was a fish said to be 7 feet long.”

None of these accounts claims to be definitive, of course; the authors treat the story like the oral history that it is, hedging with phrases like “said to be,” “so far as is known,” “according to tradition,” and “the story goes.” Most of the accounts were published before old newspapers were digitized and the written record became so much easier to comb through. So what can digital archives now tell us about the fates of the two fishermen?

One of the first things I noticed when running searches on “Abe Burns” was that he liked to supplement his fishing income with bootlegging, or perhaps vice versa. In 1911, he was fined $100 and sentenced to 60 days in jail for “violating the prohibitory law”; the Journal-World reported that he couldn’t pay and would have to join a work crew breaking rocks. Four years later, he skipped town after a drunken customer ratted him out to the cops. He left behind a brief farewell note: “Tell those punkin-heads on the police force that I have $1,500 that I made in this town selling whiskey.” I learned from a 1912 Daily Gazette article that Abe’s brother Watson was the “head trainer of Jack Johnson,” the former world heavyweight boxing champion. With this information and a hunch, I located Abe in the 1920 census, now living with Watson in Los Angeles and apparently working in the motion picture industry. According to the California death index, Abe passed away in May of that year, at the age of 53.

For quite a while, I couldn’t figure out what became of Jake Washington. But at some point, I ran a search on his street address, and a brief obituary popped up. According to the Journal-World, Jake was 78 when he died at his longtime Lawrence home on March 4, 1929. No cause of death was given, but I’m confident that a catfish didn’t kill him in his bathtub.

So it was all just a big fish story, right? Yes and no.

Fishermen did drown with some regularity on the Kaw, and monster catfish may have been the culprits on at least a couple of occasions. On June 17, 1884, a man named George Potts drowned while diving at the base of the dam: “It is supposed that he hooked onto a fish larger than he could handle,” The Western Recorder observed. After his body was recovered, another journalist noted a bruise on the side of his head, “probably caused by striking the rocks on the bottom. The strap had been pulled off from the wrist, which seems to corroborate the theory that he had hooked a large fish.”

Twenty years later, Archie “Sky” Mitchell disappeared while diving for catfish under the Bowersock mill’s disused wheel house. That was an especially high-risk, high-reward pursuit, since huge cats loved to congregate beneath the old structure, but going after them required the diver to resurface through a hole in the heavy oak floor. “Whether he hooked a fish that whipped him off his guard or he went in too far to return to the opening before his breath gave out, will never be known,” The Daily Gazette reported on August 2, 1904, the day of the drowning. “The latter theory is the more probable one, and his companions think that he merely lost his direction and became exhausted.” Abe Burns was actually one of Mitchell’s companions, and one of the divers who helped search for his body. Another riverman found him that evening, and the next day’s paper reported that “it is now known that his death was caused by getting tangled in the brush and bushes in the bottom of the river.”

In neither of these cases was it conclusively established that a big fish had done the drowning. Nevertheless, after a few years had passed, a killer catfish had clearly entered the local lore. In 1910, KU professor and famed naturalist Lewis Lindsay Dyche told a reporter that “one diver did lose his life by being carried away by a big fish at the dam some time ago. I’ve forgotten the details of it, though.” Two years later, the Journal-World referred to “the monster cat fish that once pulled a negro fisherman under the Bowersock mill race structure and drowned him.” It seems that the people of Lawrence forgot the names of the lost fishermen but vaguely remembered, or vividly misremembered, the stories of their deaths. Over time, those stories attached themselves to the two fishermen the city did remember: Abe and Jake.

In 1905, 14-year-old Floyd Miller fell into the river while angling from the dam and drowned. The Daily Gazette reported that he “was seen to come to [the] surface of the water two times struggling with a line on which he had hooked a large fish.” Both Abe and Jake dragged the river for Miller’s body. The two were often called in for such recovery efforts because of their skill as divers and their knowledge of the river. They helped prevent at least a few people from becoming bodies, as well. In 1901, a boy named Herbert Carroll, the son of a famous brigadier general, waded out too far and was washed downstream. “Jake Washington, a fisherman, appeared on the scene at this time and rescued Carroll from the bottom of the river by diving,” The Daily World reported. During a catastrophic flood in 1908, Abe Burns swam to the aid of a family in a horse-drawn buggy that had been swept into high water. He “pulled the little girl out and then went to the assistance of the man and woman,” according to The Jeffersonian Gazette, “helping the woman out while the man cut the tugs which held the horse, permitting it to swim ashore.” These occasional acts of heroism may or may not have helped to cement Abe and Jake’s place in the city’s memory. In any case, they struck me as worth remembering here.

Since 2019, a documentary about the rivermen of northeastern Kansas called When Kings Reigned has aired on the local PBS station from time to time. The filmmaker, Barbara Higgins-Dover, is the granddaughter of a lifelong river fisherman and knows more about the subject than anyone else in town. It turns out she noticed Abe Burns’s relocation to California several years before I did. But her film also includes the claim that Jake Washington “drowned trying to bring in a fish much stronger than himself.” I emailed her, drawing her attention to Washington’s 1929 death announcement and asking whether she knew of any hard evidence that he had died in a fishing accident.

She replied that she had boxed up and stored all of that research nearly a decade ago. She remembered seeing “some kind of documentation that he was carried out of the water and did not survive afterward,” but she wasn’t sure where. “I’m also from a fishing family,” she added, “and most of those men passed on the story of Jake drowning including my grandfather’s recollection.”

I was skeptical, and I told her so in my response: Jake died on March 4, “and there was an article just a few days earlier about all of the ice on the river. That seems like an unlikely time for a man who was almost 80 to be diving for big cats, even a man as river-hardened as Jake Washington.”

From her reply, I was reminded of the fact that her film didn’t say he’d been diving, only that he’d been “trying to bring in a fish much stronger than himself.” “A lot of these men fished through the ice in winter, hunted, trapped and cut ice blocks for income,” she wrote. “His age would have been a factor whether he was diving or just fishing through the ice and went into the river.”

I remain skeptical. The film does assert that he “drowned,” whereas the obituary states that he “died last night at his home.” And whereas the oral tradition Higgins-Dover invokes is a wonderful source of facts, including facts missed in the documentary record, it’s also a source of stories about dead men on sandbars hooked to seven-foot flatheads.

Still, Jake Washington was absolutely the kind of guy who would’ve gone fishing on the iced-over Kaw at age 78. And falling into water that cold could’ve been fatal even for a much younger man. Is it possible that he hooked a big fish, slipped into the river, and died at his home soon after, and that the story of his death eventually merged with the stories of earlier drownings? Am I being too deferential to the legend, or not deferential enough? This is how fish stories are supposed to end, I guess—you decide what to believe.