I first crossed an international border while on spring break during my sophomore year of college. I was staying with friends in California, and we decided to go down to Tijuana and then on to some beach towns farther south for a few days. I was generally inexperienced with travel and nervous as we approached the border agents. Sensing my discomfort, one of my friends turned to me and said, as though it were the most obvious thing in the world, “It’s no big deal, we’re all gringos.” I knew the term but had never thought it could apply to me. I protested, I was American, but I was first and foremost black, and any Mexican would be able to make the distinction. My friends let it go, though they were unconvinced.

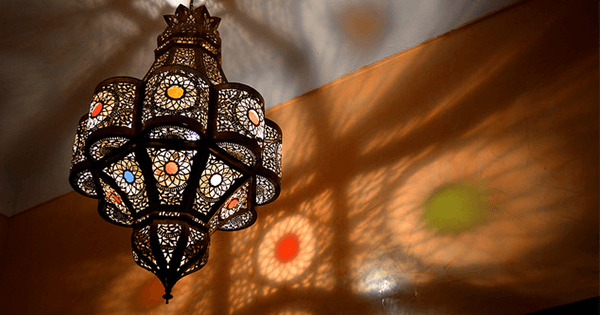

On a recent trip to the seaside town of Essaouira, in Morocco, I kept thinking about this exchange and my own lifelong incredulity and resistance to the idea of being lumped into the realm of the privileged—and in cases of tourism—the objectified and undifferentiated “white” masses. On a previous stay in Marrakech a few years back, my white father-in-law was like a polarized magnet in the souk, but this time, without him there to absorb the attention, things felt different. Outside the door to our guesthouse was the stall of an incredibly persistent Berber merchant in whose daily back-and-forth I realized how futile it was to imagine he could parse—or care to parse—the differences between my gringa wife and me. He couldn’t see that I was black; all he could see was that I had more than him. It is a strange feeling when your internal identity doesn’t register, but it’s healthy to be reminded that our own narcissistic and arbitrary systems of distinction hardly contain universal truth. They’re constructions—real enough to kill on their own turf but frivolous and possibly even insulting in a foreign land.