This week you were asked to write a two-stanza poem, in which both stanzas conclude “But I could be wrong.” A second option was to write a poem entitled “the top 10”—or to combine this task with the other.

The “I could be wrong” strategy appealed to many NLP regulars and a couple of newcomers. If there is a first prize this week, it is divided among five (just as last week we illustrated how a top-10 list could contain 15 entries). The five are Diane Laboda, Patricia Wallace, Millicent Caliban, Ravindra Rao, Emily Winakur, and Elizabeth Solsburg. That, to make a zeugma, makes six—and my point.

Necessary digression: a zeugma is the rhetorical figure in which one verb governs two nouns from different paradigms. For example, “I lost my keys and illusions last night.” “Five plus one makes six and my point.”

Diane Laboda’s “Sabbath” introduces its narrative subtext in its title:

It was your idea to speed-stack hay

on this blistering July Sabbath, high-noon sun

already dripping off corrugated roofs and bodies,

to hose down behind the barn, wash away

evidence of sinful industry. But I could be wrong.It was your idea to pile our clothes

far away on the last wagon, so when

Aunt Clara came by to bring pastor’s condolences

we were as God created us, red-faced

and headed for hell. But I could be wrong.

The great phrase here is the “sinful industry” that has been performed by “you” and “I”—referring either to work on the Sabbath day or to the enjoyment that follows nudity. The way the second stanza advances and twists the narrative in a sexual direction, as if impelled by the word “sinful,” is marvelous.

Patricia Wallace’s conversational poem begins with an echo of Wallace Stevens and makes artful use of the space between the two stanzas:

It’s snowing or it’s going to snow.

Lately the clouds have been passers-by

on a big blue curtain slung over a ridge line

completely empty of snow bones. Scary, right?

But I could be wrongabout the snow. All that clear blue

heaven doesn’t seem promising. No icicles

in the windows and this weird warm weather dispels

hopes for a wintry dazzle rightfully ours

though I could be wrong

The understated last line enacts an exemplary paradox: it comes as a surprise and yet is fully in line with our expectations. The alliteration in line eight—“in the windows and this weird warm weather dispels/ hopes for a wintry drizzle”—is darn wonderful. Well done.

Well done, too, but also rare, Millicent Caliban’s “Relative Certainty” cleverly applies the ambivalent sentiment of “I could be wrong” to a cast that includes teenage girls, Hamlet, Adam and Eve, the Trojans, and Columbus:

She’s only 14; this infatuation won’t last.

Don’t worry, Claudius, he’ll soon snap out of it.

My faith in her is absolute. Nothing could shake it.

Don’t be silly, there’s no such thing as witches.

Of course, I could be wrong.He surely won’t mind if we take just one bite.

They’re obviously seeking reconciliation by sending us a gift.

No doubt we’ve reached an island off the coast of India.

The sea is calm, the sky cloudless. No reason to be anxious.

Although I could be wrong.

It’s a keeper, Millicent, with a terrific penultimate line.

Ravindra Rao’s “Effacement, feat. Insomnia” discovers its lyricism via repetition and rhyme. This is one that could be set to music (but with maybe a more colloquial title e.g. “I Couldn’t Sleep”?):

I could be wrong, I could be

wrong. I haven’t gone to sleep in so long.

All black-blue night, I swallow the parrot-

song. My ears, I mean my fears, are almost

gone. But, of course, I could be wrong.The lake makes a mirror of the sky.

The eyes make mirrors of what lurks

in plain sight. I believe that light is a kind

of music, especially when it dances

in your eyes. But, of course, I could be wrong.

Emily Winakur’s well-titled “Second Guess” uses “the white” and “the blues” to excellent effect:

All the white roofs

remind me of you.

The quiet roads are you now;

the blues what you used to be.

I could be wrongabout you, but I’m not a poet

anymore. I speak to silence

day in—out—the seas

of it you steep in. Still,

I could be wrong.

Elizabeth Solsburg’s “It’s fate—but I could be wrong” has a knockout second stanza:

When my eyelids block the moon tonight,

I believe they will open to the soft edge of dawn

and see you beside me drawing quiet

draughts of tender new light—

but, of course, I could be wrong.I trust Clotho will spin us a tomorrow,

attenuating our thread fine, but long;

Lachesis will write our names in the day’s last hour

and Atropos’ shears will cut another’s sorrow.

But, of course, someday, I will be wrong.

Eric Fretz proffered more than one ingenious cento under the heading “The Top 10.” I particularly admired this:

It will just hang on, in its own infamy, humility. No one

Whose heart would break in two,

who lost their loveboys to the three old shrews of fate

And if it rains, a closed car at four

And you have been gone for five months.

The light behind us fades: the six are two:

Telling it five, six, seven times a day

We waited for the stroke of eight:

She lies in bed till eight or nine,

The hot water at 10.

Here are the sources as identified by Eric:

1. John Ashbery, “Rain Moving In” (A Wave, p. 2)

2. W. B. Yeats, “The Happy Townland”

3. Allen Ginsberg, “Howl” I

4. T. S. Eliot, “The Waste Land” II

5. Ezra Pound, “The River Merchant’s Wife”

6. Dante, “Inferno,” Canto IV (trans. S. Fowler Wright)

7. John Ashbery, “Written in the Dark” (Shadow Train, p. 30)

8. Oscar Wilde, “The Ballad of Reading Gaol”

9. Mother Goose rhyme: “Nancy Dawson”

10. T. S. Eliot, “The Waste Land” II

Angela Ball’s admirable “On the Commercially Complicated Way to My Las Vegas Hotel Room” has the texture of a dream. The unconscious is a subtle genius, and I would call attention to the way the author’s name sneaks into the memory:

I dropped my key.

Someone picked it up,

delivered it with

the look I knew well

from junior high gym class

when I had again missed

the ball—not an ordinary

one, but a round canvas

framework the size

of an ottoman. Of course

I could be wrong, but I thinkthe look passed itself down,

supremely inhabiting the faces

of the self-assured

whom I have thanked

for the favor of disdain—

up to and including this

lovely girl, her evening face

visiting a city already

smitten with it, her eyes asking,

What’s wrong with you?

Against all bereft

better judgement

I thanked

her coldness.

Appropriately, I now think,

though I could be wrong

My thanks to all and apologies to Diana Ferraro, whose first name last week was spelled with a terminal “e” rather than “a.” (Diana, your differing first names in different locales would make an excellent subject for a poem.) Paul Michelsen is taking a furlough and will be welcomed back with open arms whenever he decides to drop in. Finally, I would like to commend Charise Hoge for the wonderful posts she has done on the Best American Poetry blog, which I hope you will visit.

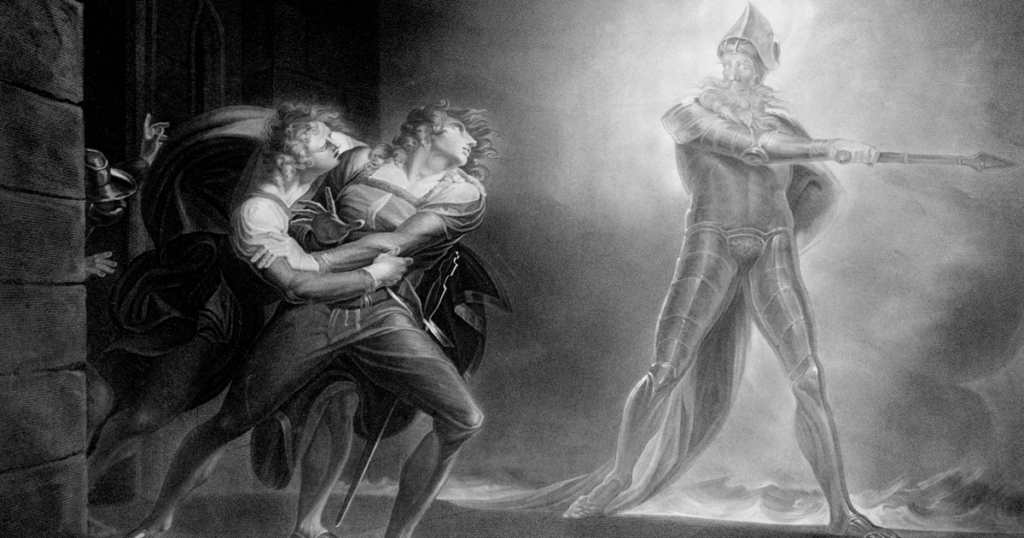

Hamlet may be the most fertile source of quotations this side of the Bible. In addition to the most famous quotations, there are, tucked in, here and there, phrases that have entered general use. If you say “get thee to a nunnery,” “to thine own self be true,” “to be or not to be,” “the play’s the thing,” or “the readiness is all,” many individuals may, and all English majors should, be able to identify the speaker. But here are five common phrases that turn up in the course of the play and in contemporary writing—without, in some cases, the writer knowing whom he or she is quoting:

More in sorrow than in anger

A hawk from a handsaw

Caviar to the general

To the manner born

Murder most foul

For next week, tell a story or make a statement in a poem (12 lines in two stanzas) or a brief prose poem that uses two or more of these phrases. (Familiarize yourself with Shakespeare’s meaning, but feel free to deviate from it.) Extra credit if you work in a zeugma—an example of which is “Ophelia lives in Elsinore and my heart.” To undertake the task you needn’t reread the first two acts of Hamlet, though this is always a good idea, but it essential that you put on an antic disposition and dress the part, for the apparel oft proclaimeth the man or woman who has that within which passes show.

Deadline: Saturday, January 27, 2018, midnight East Coast Time.