In an article published nearly five years ago, JoAnn Falletta, the music director of the Buffalo Philharmonic and Virginia Symphony orchestras, discussed that curious thing, the American symphony—curious because of the innately hybrid nature of the form. “We have taken,” Falletta wrote,

what began as an extraordinary European tradition and expanded that legacy on American soil. We have added our essential egalitarianism, our love of experimentation, our inclusiveness and our boldness to the very form of the symphony. Americans have not been bound by one definition of the symphony, and composers have applied that formal name to pieces of varying length, structure and content.

The search for the quintessential American symphony must acknowledge this: Perhaps there is no one perfect example of the form created on American soil. That very admission validates the essential underpinning of our heritage—it is a culture based upon a mosaic of different artistic expressions and perspectives.

One would be hard-pressed to name the preeminent English novel or the most representative Dutch painting; trying to do the same with the American symphony would be just as futile an exercise. We could, however, compile a list of the most essential American symphonies. As a starting point, Falletta mentioned works by Louis Moreau Gottschalk, John Knowles Paine, and Samuel Barber, as well as Duke Ellington’s symphonic Black, Brown, and Beige. To these I would add the Symphony No. 3 by Aaron Copland; the Second, Third, and Fourth Symphonies by Charles Ives; William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony; Roy Harris’s Symphony No. 3; Roger Sessions’s Symphony No. 8; and Howard Hanson’s Symphony No. 2. More recently, there have been outstanding essays in the genre by John Corigliano, Christopher Rouse, Christopher Theofanidis, and the late Steven Stucky, among others. But any list of this sort would be incomplete without a healthy dose of Walter Piston (1894–1976), whose eight symphonies are, alas, all too rarely heard in American concert halls today.

Born in Rockland, Maine, Piston grew up in Boston and attended the city’s Mechanical Arts High School, with an eye to becoming an engineer. But his inclination was toward music, and upon teaching himself the piano and violin, he began playing in dance bands and orchestras. He enrolled as a fine arts student at the Massachusetts Normal Art School, then joined the U.S. Navy during the First World War, teaching himself the saxophone and joining a Navy band. It was during this time that he became intimately acquainted with several other wind instruments, as well.

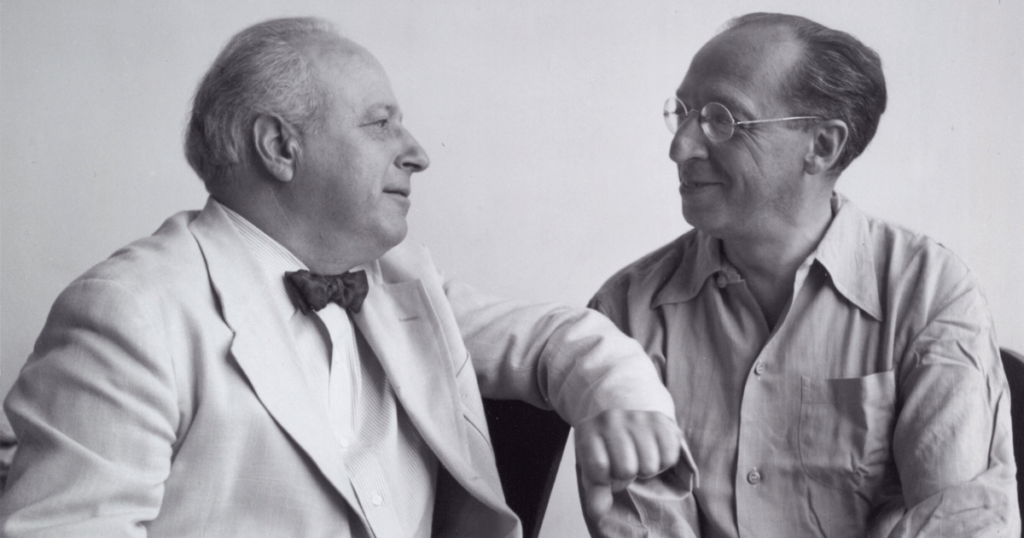

In 1920, Piston began music studies at Harvard. One of this classmates, Virgil Thomson, would later remember him, somewhat condescendingly, as a “slightly older student from the suburbs … [who] was by gift the best musician of us all. He had a good mind, too, and firm opinions. But, as for so many of Italian background [Piston’s family surname had once been Pistone], both life and art were grim, without free play.” This assessment notwithstanding, Piston flourished at Harvard, and upon graduating summa cum laude in 1924, he traveled to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger and Paul Dukas. In 1926, he returned to Harvard, where he commenced a long and influential teaching career: Piston would be a professor there, towering over the university’s music department, until his retirement in 1960. The four textbooks he wrote during those Harvard years—Principles of Harmonic Analysis, Counterpoint, Orchestration, and Harmony—are still among the most important works in the field of music theory.

Academic life gave Piston stability and the freedom to compose. His Sonata for Flute and Piano (1930) and Symphony No. 1 (1938) helped solidify his reputation. In addition to his symphonies, he composed chamber music, concertos, and the dance piece–turned–concert suite The Incredible Flutist. Stravinsky was an influence, as were Debussy and other French composers, and though he was interested in 12-tone music and incorporated the technique into many of his pieces—for example, the Chromatic Study on the Name of Bach for organ (1940), the Variations for Cello and Orchestra (1966), and the Flute Concerto (1971)—Piston’s fundamental aim was to write music that could be understood by large swathes of the concert-going public. (In this sense, he stood in stark opposition to Sessions and Elliott Carter.) Copland referred to Piston as “one of the most expert craftsmen American music can boast.” And the conductor Leon Botstein has written that the “range and quality” of Piston’s music “reveals a rare combination of elegance, wit, sparkle, craftsmanship, and a fluid and persuasive flexibility in its emotional range and authenticity.”

Although several conductors over the years, such as Leonard Bernstein, Michael Tilson Thomas, and Leonard Slatkin, have championed Piston’s works, the composer’s reputation seems to have dimmed because of his entrenchment in university life. “There is perhaps no more damning phrase among critics and in self-consciously artistic circles,” Botstein has noted, “than the word ‘academic.’” That Piston was averse to the spotlight, that there was nothing controversial about his personality, did not exactly win him popularity. He was not, in any sense, a star, nor did he have any desire to be one. For him, the music was everything, and so it should be for us.

We could begin an exploration of Piston’s symphonies almost anywhere—the Third and Seventh won Pulitzer Prizes; the Sixth may be the most accomplished of the eight. My own favorite is the Eighth (1965), a 12-tone work of power, depth, and mystery—a brooding and desolate piece of contrasting sonorities that is, to my ear, an idiomatic distant cousin of Shostakovich, its first two movements tragic and slow, its finale volatile and explosive. The Second Symphony, however, might be a better entry point, completely different from the Eighth from a harmonic standpoint, though similar in terms of architecture, length, and mood. Commissioned in 1943, it was premiered by the National Symphony Orchestra a year later. The symphony left its mark on the conductor that day, Hans Kindler, who sent a letter to Piston, telling him that the piece “sings forever in my heart and in my consciousness, and it does not want to leave me.”

It begins with a melancholic melody in the lower strings that seems at first directionless. When the violins enter, the theme unfolds almost like something out of late Sibelius, in direct contrast to the joyous, festive, and playful second subject—a bit of ragtime here, a bit of Darius Milhaud’s Brazilian fantasy Le boeuf sur le toit there. These two melodies—one solemn, the other impish—are developed and played against each other throughout this contrapuntal first movement. Just when the music is at its most ebullient, its character changes once again, with a lovely, subdued brass chorale leading to a hushed ending. The second movement Adagio continues along this somber path, though the theme here is more focused, with the clarinet singing a plangent melody above a gentle string accompaniment. The second half of this melody takes a bluesy turn—those blue notes remain throughout this elegiac movement. When the strings take over, the music becomes more dissonant, the line ascending, the intensity increasing, the anxiety building, until the trumpets pierce through the full complement of strings. Generally, the atmosphere is Romantic, the textures lush, with a wonderful spaciousness in the string writing. In the exhilarating and anguished journey toward the climax, I hear hints of Prokofiev, even Mahler—it’s easy to see why Bernstein chose this movement to memorialize Piston at a New York Philharmonic concert shortly after the composer’s death. Following the snare-drum gunshot that announces the brief third movement, we embark on a wild and rousing ride somewhat reminiscent of Shostakovich, the feeling of perpetual motion created largely by the ostinato figures in the violins. As the movement progresses, it feels more and more like a demonic dance, whirling toward a breathtaking finish.

How can one listen to this symphony (or to the Third, Sixth, Seventh, and Eighth Symphonies, for that matter) and conclude that Piston was in any way dull or academic? His idioms may not be as individual as Copland’s or Ives’s, yet his varied oeuvre is filled with imagination. In the way he made use of inherited forms, looking to the past and future at once, he was both egalitarian and experimental, and thus as American as anybody else.

Listen to the Adagio movement from Piston’s Symphony No. 2, with Michael Tilson Thomas leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra: