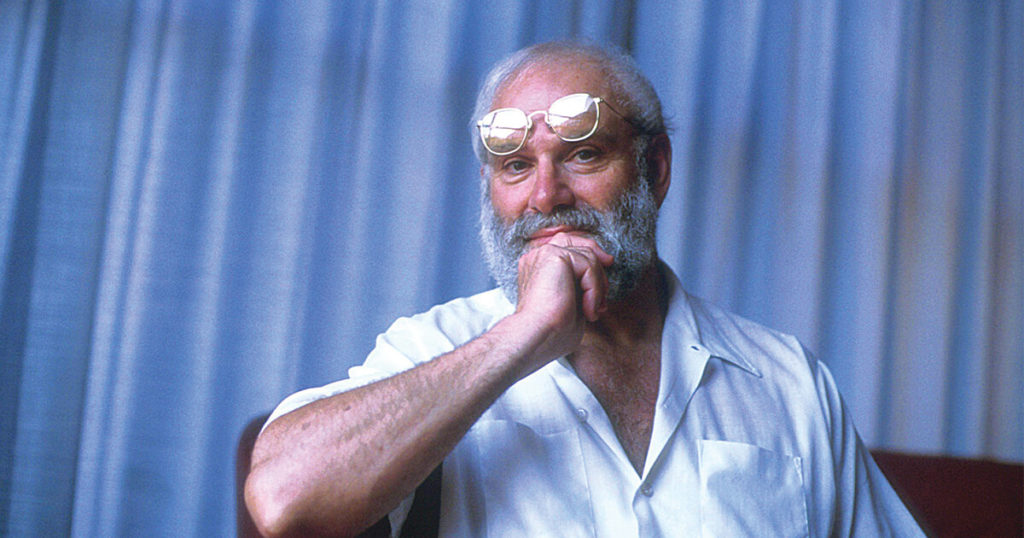

And How Are You, Dr. Sacks? A Biographical Memoir of Oliver Sacks by Lawrence Weschler; Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 400 pp., $28

Written by one brilliant writer about another, this remarkable book is, in part, about the craft of writing. But in the main, it’s an account of author Lawrence Weschler’s friendship with Oliver Sacks, a man whom he describes as “impressively erudite and impossibly cuddly.” Sacks comes across as singular. For many years, he lived by himself on City Island, not far from Manhattan, in a house he acquired when he swam out there, saw a house he liked, learned that it was for sale, and bought it that afternoon, his wet trunks dripping in the real estate agent’s office. He regularly swam for miles in the ocean, sometimes late at night. He loved cuttlefish and motorcycles, which he rode, drug-fueled, up and down the California coast when he was a neurology resident at UCLA. A friend of his from that time recalled, “Oliver wouldn’t behave, he wouldn’t follow rules, he’d eat the leftover food off the patients’ trays during rounds, and he drove them nuts.”

Sacks also had a prodigious gift for words, with which he displayed the same undisciplined intensity. Weschler calls him a graphomaniac, and indeed, Sacks wrote feverishly. He apparently completed the beautiful Migraine (1970) in just nine days, and the elegant essays that make up his Oaxaca Journal (2002), I realized with awe upon reading them, appear to be the notes he took at the breakfast table on a botanical field trip. Yet he struggled for nearly 10 years with a book about his recovery from a badly injured leg, a period during which he felt “blocked”—which meant that he wrote millions of words only to destroy them in disgust. When Sacks finally delivered the book, A Leg to Stand On (1984), Weschler went with him to his Maxwell Perkins–like editor. He recalls that she had “distilled the more than three hundred brilliant but somewhat chaotic pages of Oliver’s epilogue and addenda into a coherent thirty pages, of which the first twenty-five are quite good.” Weschler complimented the editor, and then explained to Sacks what he had to do—“five pages, not fifty, fifty will be worse than useless—five pages, Oliver!”

Weschler met Sacks for the first time in 1981, when he was casting about for a subject. Neither of them was yet famous. Weschler, still in his 20s, had just been hired by The New Yorker. Sacks had already written his masterpiece, Awakenings (1973), an account of a miracle drug that had brought people who were locked within their bodies into daylight, and then returned them, months later, to a kind of hell. Few people had paid any attention, but Weschler had read it. He wondered whether this “barely known, clearly quite idiosyncratic neurologist” might be his next subject.

Weschler spent four years chronicling Sacks’s life. There would be 15 densely written notebooks and many, many transcripts. When he sat down to write, he realized that Sacks’s hidden homosexuality lay at the heart of his remarkable capacity to hear the suffering that so many clinicians did not. “It’s not just brilliance,” a nurse had told him. But Sacks forbade him to reveal it, not until after he had died. “I have lived a life wrapped in concealment and wracked by inhibition,” he said, “and I can’t see that changing now.”

By then—around 1984—they had become close friends. Weschler had a child, and he and his wife asked Sacks to be the godfather. At one point, Sacks said that he was the kind of gay man who falls in love with straight men and then becomes god-father to their children. Later, when he knew he was dying, he asked Weschler to return to his story.

The memoir that Weschler delivers consists largely of his notes from the four-year period just before Sacks became famous, “when I was serving as a sort of Boswell to his Johnson, a beanpole Sancho to his capacious Quixote.” The chapters are the stitched-together contents of his source files: edited transcripts of his conversations with Sacks’s friends, family, and editors, along with chunks of notes from the period when Sacks’s writer’s block began to lift and accounts of rounding with him on hospital wards. There are pages on conversations over dinner, and backstories on Awakenings and other books. The chapters have the feel of notes shaken out of folders, but they are beautifully readable and detailed. You feel as if you were at dinner with him, and Oliver has just paused to take a sip of water.

Weschler is a wonderful reporter. At one point he gives us some five pages of notes from his first visit with Sacks. They are excellent, and I remember thinking: this is not the usual graduate student in anthropology. These pages are followed by an account of a day they spent on a rowboat—Sacks at the oars, Weschler with his notebook in his lap. Here is a sample:

“Over there,” he continues, indicating over his shoulder, “is the Throgs Neck Bridge. This is my favorite swim: from the island out to the pylons and back, about six miles altogether” (two beats) “although it can get a bit hazardous since the people in their motorboats don’t normally expect swimmers in these waters” (two beats) “especially late at night.” A brief pause as he turns around, reconnoitering our drift.

I love these sentences, but I am not persuaded that the words were delivered just like that or that Weschler, his notebook likely damp from the spray, captured the exact point in the story when Sacks turned the boat. The style reminds me of Joseph Mitchell, a writer’s writer, who wrote essays of stunningly precise detail and feeling, with pages and pages of quoted dialogue, although he did not use a tape recorder.

All nonfiction is factually imperfect. The most accurate text of a conversation—New Yorker writer Janet Malcolm calls it taperecorder-ese—is unreadable. All writers cast their subjects into story. The question is where you draw the line. Most people would put Weschler on the right side of the line. Where do we place Sacks, the most story-driven clinical writer of the age?

This question haunts Weschler. An old friend of Sacks’s told him, “Oliver, of course, confabulates enormously.” A negative review of A Leg to Stand On, published in June 1984 in the London Review of Books, accused Sacks of “making this stuff up.” Sacks himself said things like this: “I don’t tell lies, though I may invent the truth.” He was trying to describe subjective experiences most people cannot describe, experiences that demand he move beyond what people say with clumsy words. A neurologist friend reassured him about his 1985 book, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, “You’re describing Anton’s syndrome with considerably more intensity than Anton.” Weschler closes with a somewhat stiff defense of romantic science, writing that Sacks gave “articulation to the otherwise inarticulate through an act of active imaginative projection.”

I say this: as a reader, the more I feel I was there, the less, as a writer, I believe that things happened exactly that way. This is the conundrum of literary nonfiction. There is no simple answer, but Weschler’s is a fine book.