Bellevue: Three Centuries of Medicine and Mayhem at America’s Most Storied Hospital by David Oshinsky; Doubleday, 400 pp., $30

As a Columbia medical student, my father spent time at New York’s Bellevue Hospital in the 1960s. I grew up hearing stories of sick patients strapped to gurneys and left in the hallway because there was no space on the ward; of a rough emergency room filled with gunshot victims on the weekends; of a tubercular man in an iron lung, the metal device breathing in and out for him as he lay inside smoking.

Public hospitals such as Bellevue—the nation’s oldest, founded in 1736—are indeed unique social worlds. Funded primarily by tax dollars, they are required to accept patients other facilities might reject, and they are often overcrowded and grim, with an in-your-face human intensity that private hospitals tuck out of sight. Because public health crises tend to originate with the poor, these hospitals often see patients early in the course of a disease outbreak—and because the poor often have nowhere else to go, patients tend to stay longer. Diseases rare in the outside world are commonplace within their walls. As one doctor recalled of Bellevue, the facility at the center of New York University historian David Oshinsky’s new book, “I don’t think there was a disease in Osler’s Textbook of Medicine that I didn’t see.”

Bellevue is in part a tribute to its namesake’s role in the remarkable achievements of American medicine, but it is also a somewhat macabre history of the way medicine was practiced before anesthesia, before germ theory, and before the advent of a widely embraced moral will to help all those who suffer, regardless of their means. Take cholera, for instance, which came to a New York City slum in 1832. The disease kills its victims by inducing explosive vomiting and diarrhea, leading to massive, sudden dehydration. But in treating it, doctors at Bellevue employed bleeding and purging, which only worsened the suffering of their patients. According to Oshinsky, whose 2005 book Polio: An American Story earned a Pulitzer Prize, change came gradually, driven by immigration, war, and science, more or less in that order.

In the 19th century, epidemics raged through impoverished immigrant communities. Diseases like yellow fever and cholera found fertile breeding grounds in New York’s slums, particularly among Irish immigrants. One Bellevue physician explained that this was because the Irish were exceedingly dirty and exhausted by drink. Later, in the 1840s, Irish immigrants also came to be associated with typhus. Fleeing the potato famine at home, they were packed so tightly on boats that sickness killed one in 10 passengers during the crossing. As with yellow fever and cholera, victims of typhus ended up in Bellevue. The disease killed more than a few physicians and hospital employees, which led to a series of changes in the way the hospital was operated. Wards became cleaner and staff more professional, and in 1852, city officials ceded control over the facility to a new 10-member board of governors, consisting of social reformers and doctors.

But the effects of the typhus epidemic were felt far beyond the hospital grounds. In the 1860s, when Bellevue doctor Stephen Smith noticed that many of the victims came from one address, he went there. “The doors and windows were broken; the cellar was partly filled with filthy sewage … every available place … was crowded with immigrants—men, women, and children,” Smith wrote in his Sanitary Conditions of the City. One of the most influential public health documents ever produced, the report led to the Metropolitan Health Act (1866) and, in 1872, to the founding of the American Public Health Association. City officials moved slaughterhouses out of residential areas, placed hydrants for drinking water throughout the city, built a public urinal in crowded Lower Manhattan, and established a board of health to oversee basic living conditions. Mortality rates for residents of New York’s slums were five times those of “a better class”; among all New Yorkers, one in five died in the first year of life, and a quarter of those who reached adulthood died before reaching 30. Slowly, those rates began to fall.

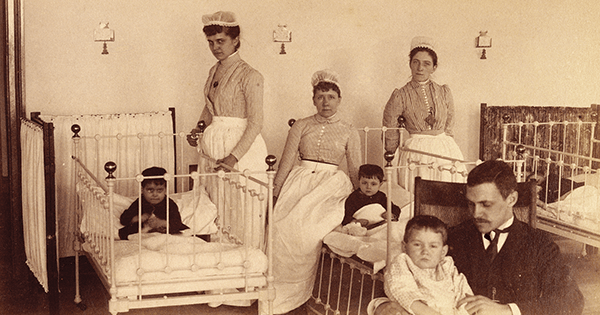

Perhaps no single event changed American medicine more than the Civil War. Despite the sometimes epic scale of the war’s battles, more soldiers died of infection than enemy fire. The need to improve care prompted the U.S. government to turn to the example set by English social reformer and nurse Florence Nightingale, whose treatment of British soldiers in the Crimea had vastly decreased mortality rates. As Oshinsky writes, Nightingale and her staff of nurses “scrubbed down the wards, emptied the waste buckets, bathed the patients, cleared their bodies of lice, laundered the bedding, and threw open the windows for fresh air.” Union hospitals followed her example, establishing light-filled, spacious “Pavilion hospitals” with improved ventilation and creating a women’s nursing corps. Bellevue was among the facilities that trained would-be nurses for duty. As Oshinsky writes, “their experiences would lay the groundwork for professional nursing in the United States.”

The improvements in hospital conditions were soon followed by two crucial scientific discoveries. During prior wars, most soldiers undergoing amputations were given some whiskey and a bullet to bite. After 1846, when the benefits of inhaled ether were first demonstrated, it was rapidly adopted (although not all soldiers were lucky enough to receive it). Germ theory proved more difficult to accept. The idea that invisible particles caused disease seemed laughable to many doctors, even though half of the patients receiving amputations at Bellevue in 1867 died within a month. Part of the problem was that many American doctors simply dismissed the idea because of its European provenance: it was a Frenchman, Louis Pasteur, who had demonstrated that decay depended on microbes, and an Englishman, Joseph Lister, who experimented with carbolic acid as a means to remove those microbes from his hands and instruments. But then, in 1881, President James A. Garfield died of an assassin’s bullet that ought not to have killed him. By the time President Grover Cleveland developed a cancerous mass on the top of his mouth in 1893, the Bellevue physicians who oversaw the secretive operation wore clean medical coats, washed their hands, and boiled their instruments. Cleveland lived for another 15 years.

Oshinsky’s story winds through more epidemics (the Great Influenza, AIDS), cures (penicillin), scandals (the exposé Ten Days in the Mad-House by Nellie Bly), and policies (Medicare, Medicaid). For the most part, we see people trying to do the right thing, although as Oshinsky points out, they often embrace change reluctantly and mostly when it serves their interests. What strikes a reader, though, is how much of our basic urban infrastructure evolved in direct response to human suffering. Today, we often take it for granted. We should not.