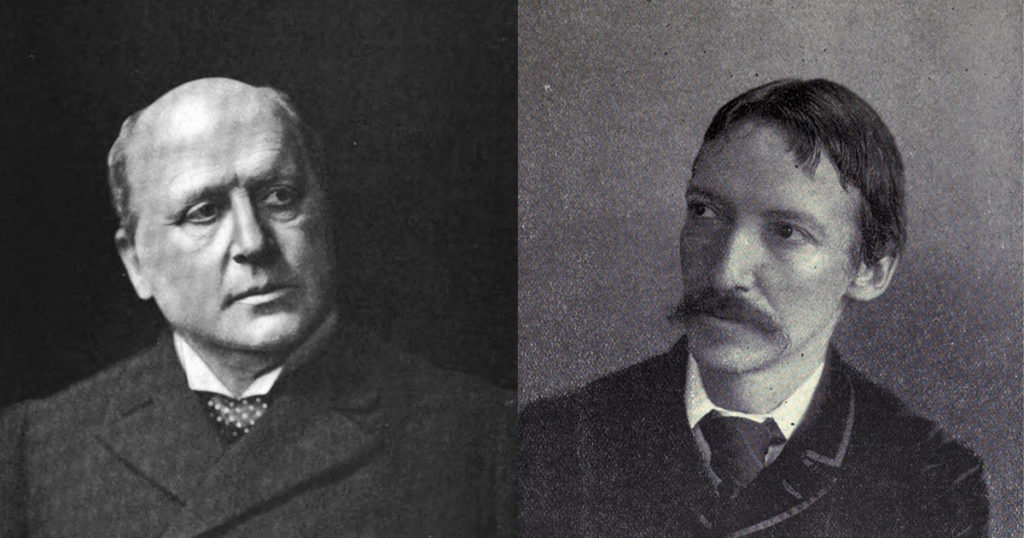

The long, warm friendship of Henry James and Robert Louis Stevenson is one of the enduring mysteries of 19th-century English literature. As different as Inside and Outside, as contrary in personality and presence as W. H. Auden and T. S. Eliot, these two giants of the late Victorian novel seem to have turned to each other as mysteriously as the needle of the compass finds the pole. From the start, readers and historians have asked what moved the great and genteel author of The Portrait of a Lady to seek out and pull so close to his heart the author of Treasure Island? What could the American novelist of drawing rooms and sensibility have to say to the sunburned Scots novelist of Hebridean landscapes and swinging cutlasses? How could they so famously hit it off?

Yet hit it off they did. When Stevenson lived in the English seaside resort of Bournemouth, from 1884 to 1887, seeking to heal his sickly lungs, James often came to the same city to visit his invalid sister, who was also convalescing there. Stevenson was 34 then, and James seven years older. Stevenson and his family had settled at a picturesque villa he named “Skerryvore” after a Scottish island, and soon enough James began to call on them. After a few weeks, he was visiting so often that a special chair—it had belonged to Stevenson’s grandfather—was formally designated “Henry James’s chair.” Stevenson wrote several poems to celebrate his elegant visitor, including one (spoken by the Venetian mirror James once gave him) that concludes: “I wait until the door / Opens, and the Prince of Men, / Henry James, shall come again.” Apart, they wrote each other often, and with a mutual affection far from common in the envy-shredded friendships of most authors.

The mirror suggests one facet of the attraction: James was nothing if not sexually ambiguous. And Stevenson, despite his lifelong battle with consumptive illness, appears to have possessed a remarkable physical beauty. The ambiguity was, however, all on one side. Stevenson was long and faithfully married to Fanny Osbourne, an American divorcée. There is no record of his having had a homosexual experience, and notwithstanding a modern (and wrongheaded) impression that Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is about homosexuality, nothing in Stevenson’s life and writings has even the faintest shading of homoeroticism.

And yet, as biographer Claire Harman writes, Stevenson’s “affect”—his way of dressing and speaking—struck people as “almost entirely ‘gay.’” Many men, whatever their orientation, found him “mesmerizingly attractive.” His friend Andrew Lang, the Scottish writer and folklorist, thought “Stevenson possessed, more than any man I ever met, the power of making men fall in love with him.” Mark Twain, of all people, described Stevenson’s “special distinction and commanding feature, his splendid eyes. They burned with a smoldering rich fire under the penthouse of his brows and they made him beautiful.” You need not be a Freudian to think of this seductive beauty when James urges Stevenson, then in far-away Samoa, to continue writing: “Roast yourself, I beseech you, on the sharp spit of perfection, that you may give out your aromas and essences!”

But this summons to write—to “perfection”—points to another, less speculative, explanation for the friendship. Almost alone among their contemporaries, James and Stevenson were deeply serious about the craft of writing.

Their friendship had begun when Stevenson replied to James’s article “The Art of Fiction,” published in late 1884. In the article, James argued that the novel, far from being simple “make-believe,” actually “competes with life.” It records experience and looks for truth in the same way that a historian does, though James’s idea of experience is impossibly gossamer—“an immense sensibility, a kind of huge spider-web, of the finest silken threads, suspended in the chamber of consciousness.” The novelist must be one of “those people on whom nothing is lost.” Here is a foreshadowing of Lambert Strether’s imperative in James’s The Ambassadors to “Live all you can!”

In a letter to James, Stevenson insisted that a novel could not really compete with life. It had to be “make-believe.” Life is “monstrous, infinite, illogical, abrupt and poignant.” But art makes it “neat, finite, self-contained, rational.” “Make believe” is no pejorative for him. Stevenson took a boy’s delight in pretending. Once, while playing with his stepson Lloyd, he drew a map on a sheet of paper and studied it for a long, pregnant moment. Then, with what we can only imagine was a shout of joy, he called it “Treasure Island” and began to write a story around it, his first novel. The writing work he did, he once explained, was “to play at home with paper like a child.” James, recognizing this élan, responded with generous tact: “The native gaiety of all that you write,” he told Stevenson, “is delightful to me.”

It is greatly to their credit that each of them saw the virtues of the other’s very different kind of fiction. James admired Stevenson’s “divine prose,” his “love of brave words as well as brave deeds.” Stevenson replied, “I recognize myself, compared with you, to be a lout and slouch of the first water.” As opposite as possible in technique and plotting, both imagined stories in “scenes” and worked tirelessly to make them, in James’s word, “transparent.” They understood the writer’s calling as a matter of high, intense, and painfully demanding Art—“perfection.”

There is one other explanation for their surprising friendship. At first Stevenson’s personal situation must have struck James like the donnée of one of his own stories—an artist of genius, a feverish invalid, determined to give full rein to his genius, yet bustled about and smothered by an entourage that could not possibly understand him or his transcendent art. James, although always gallantly polite to Fanny Stevenson, was often baffled by her role—“Poor lady, poor barbarous and merely instinctive lady.” But dimly he understood her importance to her husband, if not as muse, then as something like a mother (Fanny was nine years older than Louis). If the Stevenson household had not existed, James could have invented it.

But James, whose stories so often are about the pursuit of a larger life—the dread of timidity and reticence and dullness, the horror of missed chances—came to see that Stevenson lived such a larger life. Despite his hemorrhaging lungs, Stevenson played out in the open, fearlessly—he trekked alone through France, camped among the silver miners in California, canoed in Belgium, crossed North America by train, and spent his last years building a home in the jungle of Samoa. He was one of those people on whom nothing is lost, though not precisely in the sense that James meant.

Their correspondence is filled with discussions of books, the latest novels from France, ordinary chitchat—Stevenson sends James cloth from the South Seas, and James charmingly replies: “I have covered a blank wall of my bedroom with an acre of painted cloth and feel as if I lived in a Samoan tent.” Readers of their correspondence will find the gossip fascinating. They both mock literary lions in a way to make a pious English teacher gasp— James speaks of “the infant monster of a Kipling.” He and Stevenson take turns hacking at “the good little Tommy Hardy,” in James’s phrase; Stevenson considers Tess of the d’Urbervilles “one of the worst, weakest, least sane … books I have yet read.” Cheerfully, he remarks that he has “no use” for Anatole France.

But entertaining as these later letters are, I like the earliest ones best, the moments when the two writers discover in each other an unexpected mutual delight. I find myself thinking back to their first meetings in wet, dreary Bournemouth, before their great futures have yet fully opened up. James comes through the door, out of the cold, rubbing his hands together shyly as he approaches the fire. He has a beard and hair close-cropped in the Paris fashion. His manner, as English poet Edmund Gosse would say of him, choosing his last adjective with extraordinary insight, is “grave, extremely courteous, but a little formal and frightened.”

Stevenson rises to his feet, also rubbing his thin hands together against the cold, smiling, saying something in French with a Scots burr. There is Henry James’s chair. There are the books. There are the two friends, who, like most friends, complete each other: one definition, after all, of love.