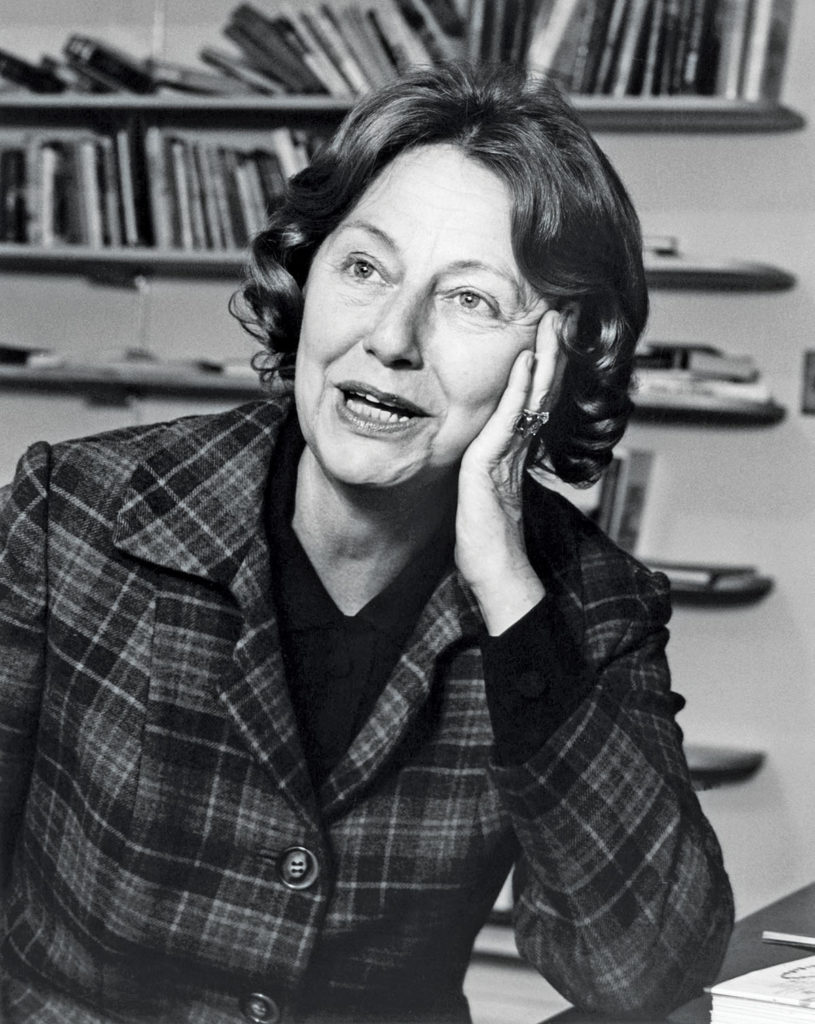

A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick by Cathy Curtis; Norton, 400 pp., $35

“A shilling life will give you all the facts,” declared W. H. Auden in his sonnet “Who’s Who.” Cathy Curtis’s A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick costs more than a shilling, but it is rich in facts. In view of her subject’s suspicion of biography as a genre, it must have taken courage for Curtis, who has also published books on artists Grace Hartigan, Nell Blaine, and Elaine de Kooning, to embark on this one. Hardwick, after all, smacked aside Carlos Baker’s biography of Ernest Hemingway, calling it “bad news” and “only an accumulation, a heap.” Of Joan Givner’s account of Katherine Anne Porter, Hardwick wrote, “the root biographical facts have the effect of a crushing army. Everything is under the foot.” Curtis’s book has, strangely enough, a similar feel. Massive amounts of information are hauled in freight cars that slam into the railroad siding, chapter by chapter, to be unloaded and stacked in the reader’s mind. A lifetime of personal calendars and bibliography is delivered. Hardwick’s style and intellect appear only when her own words are quoted.

One is grateful to learn about Hardwick’s background, education, and literary adventures. Facts can be fruitful—one doesn’t need to be Dickens’s Thomas Gradgrind to honor them—but it is hard to fathom a biography of a finely tuned writer composed in cliché-ridden prose. On the book’s first page, for example, we read that Hardwick, abandoned by her husband, the poet Robert Lowell, “remained deeply invested in his brilliant career”; that “her star continued to rise in the literary firmament”; that “her Southern charm cloaked a rapier wit.” And so we stagger on, meeting “her gimlet eye,” “resounding success,” social life “in full swing,” trying to catch the frequency of the writer who called Hart Crane’s parents “curdling and outrageous,” who praised Simone de Beauvoir’s “nervous, fluent, rare aliveness,” who described the main character of Christina Stead’s 1940 novel, The Man Who Loved Children, as “modern, sentimental, cruel, and as sturdy as a weed.” When Hardwick writes, the page catches fire. Her adjectives hum with electrical current. Argument crystallizes in image: a bland book review is shaped “into a small, fat ball of weekly butter”; Robert Frost “is two picture puzzles perversely dumped into one box”; Delmore Schwartz, at the end, sheds wives and friends, “angrily plucking them off like flies on the worn threads of his jacket.” She is the mistress of epigram: “Self-love is idolatry. Self-hatred is a tragedy.” It is because Hardwick wrote such sentences that readers should want to know about her life.

We turn, then, to the contents of those freight cars. Hardwick was born in 1916 in Lexington, Kentucky, one of 11 children. She later portrayed her shabbily genteel neighborhood in her first novel, The Ghostly Lover (1945). This was the segregated South: white and Black families lived close to one another but in different worlds. Hardwick’s mother was occupied with taking care of the house and the swarm of children, while her father seems to have been a charming, not entirely effectual or honest plumber. We follow Elizabeth (as Curtis calls her throughout the book) through the excellent Henry Clay High School to the University of Kentucky, where she made literary and left-wing political friends, read Partisan Review, and took a summer course in poetry with John Crowe Ransom. In 1939, she hopped a Greyhound bus to New York to enter the graduate program in English at Columbia.

Curtis traces the mystery and revelation of the central story: a writer giving birth to herself. We observe the ferocious talent and determination that led this young woman, after dropping out of Columbia, through hardscrabble years in New York. She published short stories in the New Mexico Quarterly, The Yale Review, and The Sewanee Review, as well as The Ghostly Lover, which brought her to the attention of Partisan Review. Curtis’s book gathers momentum with the stream of stories and reviews that Hardwick began contributing to Partisan and other magazines and her initial encounter with Lowell in 1947. They married two years later. The couple led a peripatetic life for a while, then settled in Boston and had a daughter. Later, they moved to New York City, where in 1963 Hardwick helped to found The New York Review of Books. Through the melodramas of Lowell’s fame, infidelities, and mental breakdowns, Hardwick held the family together until Lowell ran off with the Anglo-Irish writer Caroline Blackwood in 1970.

Miraculously, Hardwick not only persisted but grew in her art. In 1955 came her second novel, The Simple Truth, a slightly supercilious, crystalline social comedy about a murder trial she attended in Iowa City while Lowell was teaching there. In retrospect, the book seems like preparation for her late masterpiece, the fictive memoir Sleepless Nights, published in 1979 after Lowell’s death. Curtis dutifully documents the sad, sordid muddle of the Blackwood adventure but rightly resists reducing Hardwick to the role of supporting actor in the Robert Lowell blockbuster.

“Courage under ill-treatment is a woman’s theme,” Hardwick would write in an early version of Sleepless Nights. Courage she had in abundance, along with piercing insight, intelligence, independence, and a signal lack of self-pity. In her 1974 essay collection, Seduction and Betrayal, she saw deeply into the endeavors of women writers, pointing to “a steady experience of the catastrophic” of the Brontë sisters and Sylvia Plath’s “strength, ego, drive, endurance” (as well as her “ungenerous nature and unrelenting anger”). Perhaps most movingly, Hardwick celebrated Virginia Woolf’s “achievement in the face of the hideous distractions of madness.” It’s hard not to feel a double purpose in that phrase: a compassionate appreciation of Lowell’s achievement in the face of his madness, and Hardwick’s sense of her own fortitude in the face of it. With a tinge of sadness, she notes that Woolf’s “devotion and gratitude” for her husband Leonard’s care “are part of a larger, more courteous, and loyal time.”

Curtis marches steadfastly through the many facets of Hardwick’s life. Most helpfully, since one won’t find these remarks elsewhere, she cites descriptions of Hardwick’s teaching from her students at Barnard, including Elizabeth Benedict, Susan Minot, Mary Gordon, Anna Quindlen, Daphne Merkin, and Sigrid Nunez. Something of Hardwick’s spirit survives in the vision of art she imparted to these gifted women. But her essence is to be found in her own pages: in The Collected Essays, Seduction and Betrayal, The New York Stories, and Sleepless Nights, all handsomely reprinted by the New York Review Books Classics, the publishing venture that sprang from the formidable journal she helped bring into being.