Hey Siri, Call Webster

When it comes to learning new words, it’s not where you look them up that’s important

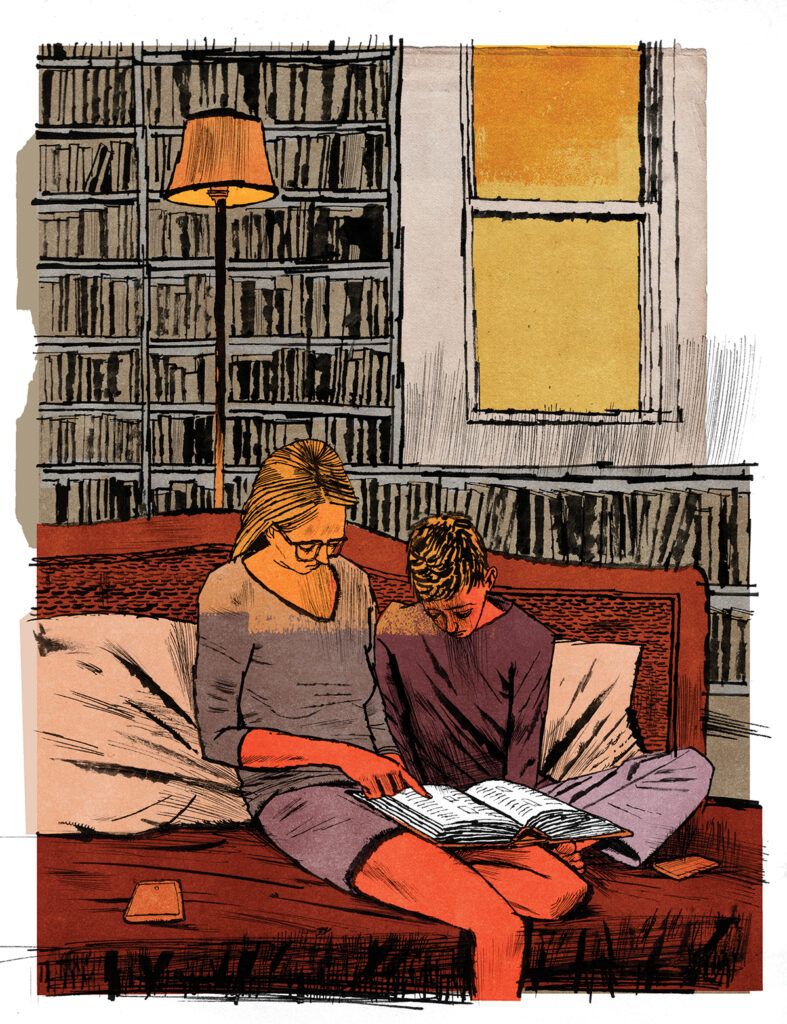

Not long ago, my son asked me about the meaning of a word in a novel he was reading for his fifth-grade book club.

“Look it up,” I responded, my automatic rejoinder when my children ask me the meaning of a word, which is often.

“But my screen time is off,” he whined. We were sitting next to a bookshelf that held at least three dictionaries, plus a thesaurus. I looked pointedly at the shelf, and my son sighed dramatically. “Can’t you just use your phone?” he asked.

A terrifying thought occurred to me. “Do you even know how to use a dictionary?” This was my second son, and it turned out that my sureness of having taught him something was often a transplanted memory of having taught that very thing to my firstborn.

“Of course,” he scoffed. “Every chapter is a different letter.”

I laughed out loud at this idea. I’d never thought of the dictionary as having chapters, as something that might be read sequentially from beginning to end.

We pored over a paperback dictionary together for a few minutes before I handed it to my son. It took him a few tries to find the word in question (peripheral), and he was overwhelmed by the idea that there could be an entire page—pages!—devoted to words that share the same three beginning letters. He kept saying: “How can there be this many words?” He asked this with alternating horror and awe.

I wanted him to land squarely in the awe category. But I knew from experience that if I pushed too hard, he’d just shut the book. So I concentrated on my own work as he continued to browse.

After a few frustrated minutes, he looked at me with surprise. “Do you know all these words, Mom?”

I am an English professor, and he often assigns strange functions to my job, imagining the classes I teach to be a mix of book club, Scratch class, and the soul-numbing five-paragraph essay. I rarely explain that these things don’t really exist in college. “I definitely do not know all these words,” I said. “But that’s why this is one of my favorite books.”

I was just a bit older than my son is now when I decided that I wanted to learn as many words as I could and started marking every entry I looked up in the dictionary with a small penciled dot. I don’t know where I got this idea. I remember feeling stolen from, my face burning in the dark, while watching the scene in Say Anything when Diane Court tells Lloyd Dobler that she used a pen to mark the words she looked up in her obscenely huge dictionary. My dictionary was also obscenely huge, the kind with onionskin paper and gold leaf on the cutaway thumb tab for each letter. Diane’s dictionary was covered in Xs; mine was filled with graphite—a strange, silvery Morse code dotting its pages.

The dictionary was a gift for my 13th birthday. Books, especially new books, were hallowed in my house. Although neither of my parents was able to go to college, they both made clear that my education was a family priority. This dictionary seemed like an embodiment of what I’d need to know to get into college one day. And so I took to measuring my progress. In her book Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance, the psychologist Angela Duckworth argues that this inclination toward self-challenge is far more important as a measure of success than talent or intelligence. I agree that my impulse to set goals and my tendency to work harder than the next person have been more helpful in my life than any score I ever received on an IQ test or the SAT. But mostly, I marked up my dictionary because I enjoyed the process, took pleasure in the visual tabulation. I didn’t set out to learn every word. I did it for the experience, for the pleasure of participation, not the result, a rare thing in those days. I continued to make these pencil marks for years, and when I did finally go off to college, I packed that dictionary in my suitcase.

After my son finished his homework that evening, I reshelved the paperback dictionary. He did not place a dot by his word, and since that day, I haven’t seen him take the dictionary down once. I have, however, heard him ask Siri to define many more words. I try not to let this scare me, and yet, I worry that things are too easy for my children, that asking Siri to define words instead of hunting for them on their own in a paper dictionary will soften and ultimately dull their brains. I want to keep them sharp, but I don’t know how to do this in today’s world, where every single definition of every single word is only a voice query away.

A few days later, my son asked me about my dictionary, the one I marked up. He wanted to see it. A small pain gripped my chest at the memory. “The book is gone,” I said.

The dictionary was stolen at the end of my freshman year of college. I had used the book to prop open my old double-hung dorm window, and someone walking by just plucked it from the sill when I wasn’t looking.

“That’s so sad,” he said. “I wish I could see all the words you know.”

I thought about this. When they were toddlers, I used to write the words my children could say in chalk on our bluestone patio. I loved seeing the list grow, extend to more and more of the pavers until we couldn’t squeeze any more words in. I thought about all of my own dictionary words climbing out of my childhood bedroom and down to the street, extending into the distance, making a bridge of letters to my college dorm room.

My son paused, thinking, then said, “But you still know all those words, even without the book.”

I realized that this was true. I imagined my dictionary with its little dots, moldering in a secondhand bookshop or turning to mulch at the dump. I still made it through the next three years of college, even without my book. And it wasn’t, ultimately, the dictionary that got me there—not really.

I remembered that although my children loved to watch me chalk out their words, what they loved even more was helping spray down the stones with the hose afterward, watching the color disappear until our patio resembled a computer screen gone blank. And I understood that although my son may be learning differently, he is still learning. It’s not about the words themselves or how we learn them, but the wanting to know them, the curiosity and the appetite.