How Many Words Does a Wordsmith Make?

On Aesop Rock, DMX, and the importance of a large vocabulary

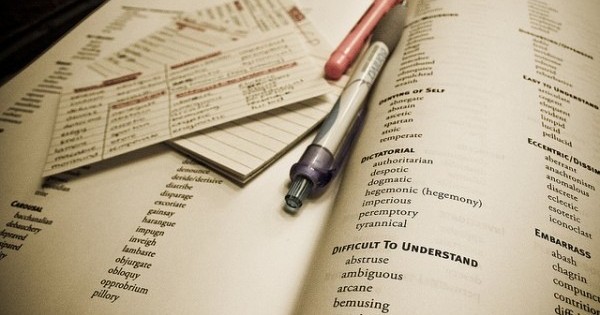

What does it mean to have a large vocabulary? To throw around hibernaculum and obstreperous, parsimony and rapscallion—or even rock-bottom-brow slang terms—in contexts you might not expect?

The question has been on my mind thanks to a recent analysis of the “largest vocabularies” in hip-hop that has monopolized my Facebook feed for the better part of a week now. Data scientist Matt Daniels grabbed 35,000-word lyric samples from a number of rappers, tallying up the number of unique words each contained. Aesop Rock wins the contest handily, exceeding even Shakespeare, whose renowned vocabulary is used as a benchmark for verbal creativity. At the other end of the spectrum are DMX and 50 Cent. And Daniels notes an interesting regional trend too: “The south has the lowest average (4,268) and the east-coast the highest (4,804),” he reports. “In fact, only 4 of the 17 southern-based artists in the dataset are above average.”

For his part, Daniels is careful not to suggest that vocabulary size is a good proxy for quality or originality or cleverness. (Regional differences are likely “a function of crunk music’s call-and-response style, resulting in more repetition of words”; DMX’s last-place finish “shouldn’t undermine an artist whose raw energy and honesty were the most memorable qualities of his music.”) And yet, the idea that a large vocabulary does equate to quality and originality and cleverness—that knowing and using more words allows us to express richer, more nuanced, better thoughts—is practically an article of faith in our society.

Is it true? As anyone learning a new language can attest, without a large and varied enough vocabulary, forget philosophizing about societal ills: it’s hard enough to simply order lunch. And having a handy term for an otherwise slippery, subtle, or uncomfortable concept—here the currently in-vogue “privilege” comes to mind—is no doubt helpful, both in the middle of a conversation and afterward, as we try to remember it.

But—and this is Linguistics 101 here—not having a specific word for a concept does not preclude someone from having a way of thinking or talking about that concept. Except in a smattering of minute (and not always replicable) ways, language doesn’t shape thought. It just doesn’t. And what we can think, we—as fluent speakers of a language, regardless of whether we’re literate or well-traveled or prefer DMX to Aesop Rock—can communicate.

Indeed, despite the common perception to the contrary, a typical writer today “uses far more words than Shakespeare,” linguist David Crystal explains in his book “Think on my Words.” Why? “There are simply far more words available to be used now, compared with Shakespeare’s time.” Most of us have larger vocabularies than our predecessors by virtue of speaking a language that has grown, and been painstakingly documented, for centuries.

So what is this really about then? What does acquiring a large vocabulary really mean, if not that we at last possess the requisite tools for engaging with big ideas? Intelligence seems to be the biggest stake. Given that vocabulary size is often used to determine IQ, their coupling in public consciousness should come as no surprise. And even nonverbal qualities associated with intelligence—being a swift learner, having a memory like a bank vault—can help someone acquire a hefty vocabulary.

But intelligence isn’t the only factor at play here. Vocabulary size is also highly correlated with socioeconomic status. Score high on a vocabulary test? You’re likely to be wealthier and more educated than a typical English speaker. Your parents, also wealthy and educated, spoke to you more as a child. Today you read more. You have access to a standard dialect of English—complete with appropriate cultural references—that helps you nab and keep jobs. You can navigate bureaucratic mazes. You may even be able to spell “bureaucratic.”

Further complicating things, identity also figures into vocabulary size. Vocabulary is a point of pride among bookworms and writers and amateur lexicographers, the word nerds and language geeks and word-of-the-day freaks for whom a rare term is a keepsake, a swelling vocabulary more delicious than a bodice ripper. In her essay “The Joy of Sesquipedalians,” Anne Fadiman writes of one such friend: “No man ever remembered the face, dress, and perfume of an old lover with fonder precision than Jon remembered that glorious day when he and monophysite first met.”

And then, as Daniels himself alludes to, there is the not-so-small matter of style. Using words is by no means the same thing as knowing them. Some artists cling tightly to a particular vernacular or register. Others let repetition pack wallop after wallop after wallop. And then there are the artists who, as Donald Davie once said of Gerard Manley Hopkins, “could have found a place for every word in the language if only he could have written enough poems.”