How to Read Dante in the 21st Century

Breaking the code of “The Divine Comedy” with patient reverence

già volgeva il mio disio e ’l velle,

sì come rota ch’igualmente è mossa,

l’amor che move ’l sole e l’altre stelle.now my will and my desire were turned,

like a wheel in perfect motion,

by the love that moves the sun and the other stars.

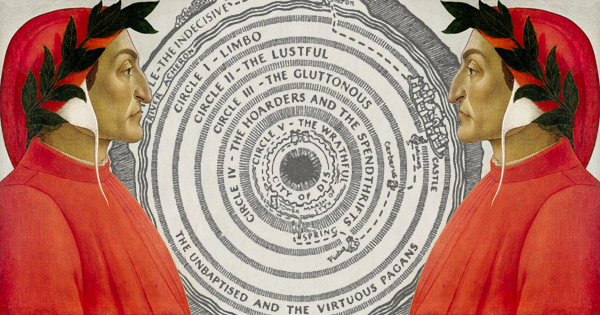

These breathtaking lines conclude Dante’s Divine Comedy, a 14,000-line epic written in 1321 on the state of the soul after death. T. S. Eliot called such poetry the most beautiful ever written—and yet so few of us have ever read it. Since the poem appeared, and especially in modern times, those readers intrepid enough to take on Dante have tended to focus on the first leg of his journey, through the burning fires of Inferno. As Victor Hugo wrote about The Divine Comedy’s blessed realms, “The human eye was not made to look upon so much light, and when the poem becomes happy, it becomes boring.”

In truth, some of the most sublime moments in The Divine Comedy, indeed in all of literature, occur after Dante makes his way out of the Inferno’s desolation. But Hugo’s attack suggests the particular challenge in reading Dante, whose writing can seem remote and impenetrable to modern tastes. Last year marked the 750th anniversary of Dante’s birth in 1265, and as expected for a writer so famous—Eliot claimed “Dante and Shakespeare divide the modern world between them; there is no third”—the solemn commemorations abounded, especially in Italy where many cities have streets and monuments dedicated to their Sommo Poeta, Supreme Poet. Yet Dante has the unenviable fate of having become more known than read: his name is immediately recognizable, his achievements justly acknowledged, but outside the classroom or graduate seminar, only the hardiest of literary enthusiasts pick up his Divine Comedy. Oddly enough, and at least in the United States, we seem to know more about Dante the man—his exile, his political struggles, his eternal love for Beatrice—than his poetry.

Part of the problem lies in the difficulty that Dante poses for English translation. He wrote in an intensely idiomatic, rhyme-rich Tuscan with a surging terza rima meter that gives the poem its galloping energy—a unique rhythm that’s difficult to reproduce in rhyme-poor English separated from Dante’s local vernacular by centuries. The content of Dante’s writing presents an even bigger problem. Unlike the other author he supposedly shared the world with, Shakespeare, Dante was self-consciously scholarly and intellectual, filling his verses with allusions to ancient, biblical, and contemporary medieval writing, and tackling a range of theological, philosophical, political, and historical issues. And then there are all those characters! From Inferno 1 to Paradiso 33, scores of different literary personae—some real, some invented, some famous, some obscure—take the stage to plead their case or expound on their joy before the autobiographical character Dante as he journeys from hell to heaven. So in order to “get” Dante, a translator has to be both a poet and a scholar, attuned to the poet’s vertiginous literary experimentalism as well as his superhuman grasp of cultural and intellectual history. This is why one of the few truly successful English translations comes from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, a professor of Italian at Harvard and an acclaimed poet. He produced one of the first complete, and in many respects still the best, English translations of The Divine Comedy in 1867. It did not hurt that Longfellow had also experienced the kind of traumatic loss—the death of his young wife after her dress caught fire—that brought him closer to the melancholy spirit of Dante’s writing, shaped by the lacerating exile from his beloved Florence in 1302. Longfellow succeeded in capturing the original brilliance of Dante’s lines with a close, sometimes awkwardly literal translation that allows the Tuscan to shine through the English, as though this “foreign” veneer were merely a protective layer added over the still-visible source. The critic Walter Benjamin wrote that a great translation calls our attention to a work’s original language even when we don’t speak that foreign tongue. Such extreme faithfulness can make the language of the translation feel unnatural—as though the source were shaping the translation into its own alien image. Longfellow’s English indeed comes across as Italianate: in surrendering to the letter and spirit of Dante’s Tuscan, he loses the quirks and perks of his mother tongue. For example, he translates Dante’s beautifully compact Paradiso 2.7

L’acqua ch’io prendo già mai non si corse;

with an equally concise and evocative

The sea I sail has never yet been passed:

Emulating Dante’s talent for internal rhymes laced with hypnotic sonic patterns, Longfellow expertly repeats the s’s to give his line a sinuous, propulsive feel, which is exactly what Dante aims for in his line, as he gestures toward the originality and joy of embarking on the final leg of a divinely sanctioned journey. Thus, Longfellow demonstrates the scholarly chops necessary to convey Dante’s encyclopedic learning, and the poetic talent needed to reproduce the sound and spirit—the respiro, breath—of the original Tuscan.

But Longfellow’s English can sound “flowery” to our contemporary ears. And it’s hard enough to read Dante without throwing in the additional challenge of 19th-century poetic diction.

So what’s the contemporary reader to do—how best to approach Dante 750 years after his birth?

Start by treating The Divine Comedy not as a book, with a coherent, beginning, middle, and end, but rather as a collection of poetry that you can dip into wherever you like. A collection of 100 poems to be exact, one for each canto, some more sublime than others. Breaking the poem down to its parts, getting to know the characters one or two at a time, learning the themes and language of these individual elements, can give you the traction to begin enjoying Dante and eventually take on his whole poem.

In other words: treat the poem as Dante the character treated his journey, something to be undertaken step by step.

For centuries, readers have been isolating “greatest hits” from The Divine Comedy and swooning over its most memorable characters: muse Beatrice, stalwart guide Virgil, tragic lovers Paolo and Francesca, unbearably eloquent Ulysses, cannibalistic Ugolino. The contemporary reader would do well to follow this ancient practice, for it leads to the most important aspect in approaching Dante: the need to read him closely.

Jorge Luis Borges said that a modern novel requires hundreds of pages for us to get to know a character, while Dante can lay bare a character’s soul in 20 or 30 lines. Perhaps nowhere is this economy of expression more evident than in the justly celebrated canto of the star-crossed lovers, Francesca da Rimini and Paolo Malatesta. These two lovers, condemned to an eternity in the Circle of the Lustful, pose a heart-wrenching question—one, as I wrote in my In a Dark Wood, that those of us who have lost our earthly loves know all too well: how do you love somebody without a body? Paolo and Francesca are technically “together,” as they whirl around “like doves summoned by desire” in Inferno’s punishing winds. But they are incorporeal shades, lacking the one thing that made their passionate earthly love possible: a physical being. Hence their eternal torment, with Paolo in a silent stream of tears, Francesca pouring out an ocean of self-defense. Dante asks her why such a courteous and well-spoken creature as she—a highborn lady who had fallen for Paolo innocently enough one day when they were alone together reading—could find herself among the damned.

“Love absolves no beloved from loving,” she explains, adding: “Love brought us to one death. The bottom of hell waits for him who extinguished our life”—referring to her husband, the nasty Gianciotto or John the Lame, who murdered Paolo and her on the spot when he discovered them in flagrante after their fateful reading.

Dante requires what Nietzsche called “slow reading”—attentive, profound, patient reading—because Francesca’s sparse, seemingly innocent-sounding words speak volumes about the kind of sinner she is. In the first place, she’s not “speaking” to Dante in a natural voice; she’s alluding to poetry. And it’s a very famous poem, Al cor gentil rempaira sempre amore, “Love always returns to the gentle heart,” a gorgeous medieval lyric by Guido Guinizelli, one of Dante’s poetic mentors in the Sweet New Style, a movement in the late 1200s that nurtured Dante’s emerging artistic sensibilities. Francesca, by citing the poem and the Sweet New Style, is saying: it wasn’t my fault, blame it on love. Despite her prettiness, her sweetness, and her eloquence, she is like every other sinner in hell: it’s never their fault, always someone else’s. They never confess their guilt, the one thing necessary for redemption from sin. With one deft allusion, one lyrical dance amid the ferocious winds in the Circle of the Lustful, Dante delivers a magnificent psychological portrait of Francesca’s path to damnation.

When he hears Francesca’s words, Dante faints—“caddi come corpo morto cade,” “I fell as a dead body falls.” A friend of mine once said of Shakespeare that everything you need to read him is right there on the surface, in the language of his plays. You don’t need to know the background, backstory, allusions, sources. I agree—but Dante is the opposite. So much depends on what’s outside his text: the mass of other books, other stories, other issues that lie submerged beneath the actual lines of The Divine Comedy. To understand why Dante faints in Inferno 5, you have to realize just how surreal it was for him to hear Francesca cite the poetry of his youth, the words that helped make him poet and that hastened Francesca’s demise.

It’s not easy to break the code of The Divine Comedy, a work steeped in a medieval Christian vision that can cause readers like Victor Hugo to avert their eyes from its more celestial passages. But the miracle of literature is that its insights can somehow remain fresh and relevant centuries after they were written and far from where they first appeared. And that’s the miracle of Dante: somehow his writing still makes sense seven centuries after it was conceived, so long as we manage to read slowly, between, behind, and around what he called his versi strani, strange verses.