The Body: A Guide for Occupants by Bill Bryson; Doubleday, 464 pp., $30

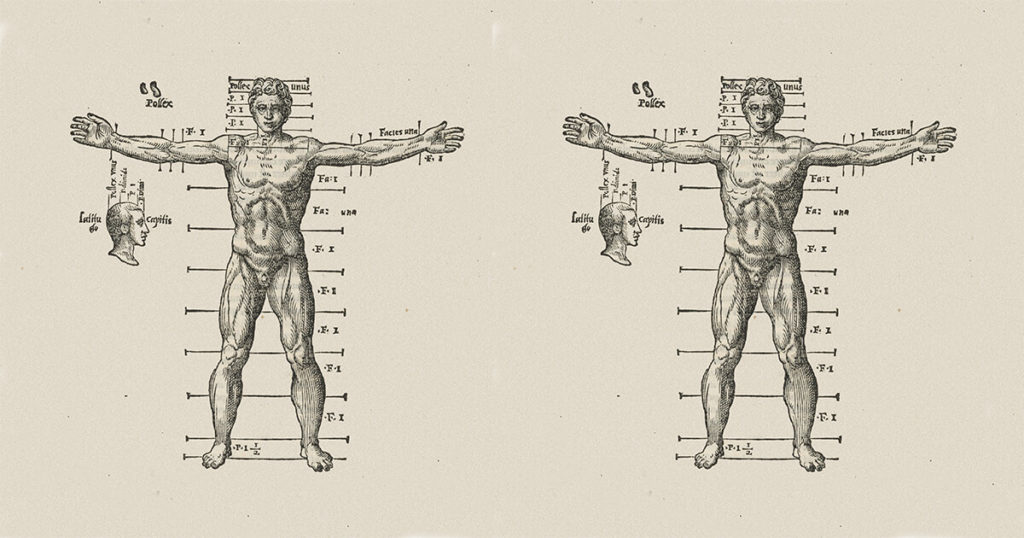

In The Body: A Guide for Occupants, his latest amble into the realm of natural science, Bill Bryson is not so much a discoverer of new lands as a charismatic cartographer of existing ones, smartly mapping points of entry into territory that might otherwise remain impenetrable to curious travelers. With light-footed prose, The Body winds its way through the dense terrain of anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry, elucidating for the reader how the human form functions. The result is an absorbing catalog of the human body in all its firmness and frailty. Bryson revels in the sublime intricacy of atoms, DNA, stem cells, cytokines, hormones, eyeballs, guts, neurons, joints, sweat glands, hair follicles, zygotes, and a great deal more. Along the way, he sprinkles existential asides about the body’s resistance to being fully known—even as it ultimately comes to know death.

The colossal roster of facts on display is dazzling: “[Y]our private load of microbes weighs roughly three pounds, about the same as your brain,” Bryson informs us. “Every time you breathe,” he goes on, “you exhale some 25 sextillion (that’s 2.5 × 1022) molecules of oxygen—so many that with a day’s breathing you will in all likelihood inhale at least one molecule from the breaths of every person who has ever lived.” There are “as many connections ‘in a single cubic centimeter of brain tissue as there are stars in the Milky Way,’ ” he adds, quoting the neuroscientist David Eagleman. “The average grave is visited for only about fifteen years,” he explains with wry pathos, “so most of us take a lot longer to vanish from the earth than from others’ memories.”

In the interstices between these facts emerge numerous penetrating observations. Describing the outermost surface of the epidermis, consisting entirely of dead skin cells, Bryson remarks: “all that makes you lovely is deceased. Where body meets air, we are all cadavers.” And though this volume doesn’t possess the celestial luster of Bryson’s book about the universe, A Short History of Nearly Everything (2003), it is often filled with imagery that transports the reader from the human to the cosmic with linguistic swerve. Enumerating the vast lengths of DNA packed into all our cells, he notes: “there is enough of you to leave the solar system. You are in the most literal sense cosmic.” More comically, Bryson describes spermatozoa as the heroic “astronauts of human biology, the only cells designed to leave our bodies and explore other worlds.” Adding: “But on the other hand, they are blundering idiots.”

When not launching himself into interstellar space, Bryson flirts with the vastness of time itself. “[T]he genes you carry,” he tells us, “are immensely ancient and possibly—so far anyway—eternal.” Other times he zeroes in on the limitations intrinsic to the body: cancer, Bryson writes, is “your own body doing its best to kill you. It is suicide without permission.” Turn by turn, our guide’s mind reveals itself.

Bryson also offers profiles in miniature of the nameless heroes, twisted quacks, unyielding innovators, and addled geniuses who have explored the body’s mysteries. Some characters swagger onto the page. Take William Halsted, the audacious surgeon who performed gallbladder surgery on his mother on a kitchen table in their family home, transfused two pints of blood from his arm into his sister as she lay near death after childbirth, became the first professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins Medical School, and invented the radical mastectomy on his way to becoming “the father of American surgery”—mostly while addicted to cocaine and morphine. Other figures, like Walter Freeman, the American doctor who wrecked countless patients (including John F. Kennedy’s sister) by lobotomizing them with “a standard household ice pick [inserted] into the brain through the eye socket,” make us recoil.

Tidbits of history are stitched into the narrative as well. We learn about the unlikely link between World War I mustard gas bombs—which, it was discovered, slowed the creation of white blood cells—and the birth of modern chemotherapy. In a section on the anatomy of the head, Bryson takes a brief detour into the history of decapitation, telling us that “Mary, Queen of Scots, needed three hearty whacks before her head hit the basket,” noting that “hers was a comparatively delicate neck.” In 1803, he writes, scientists looking for evidence of consciousness after decapitation, “pounced on the heads as they fell [from the guillotine] and examined them immediately for any sign of alertness, shouting, ‘Do you hear me?’ ” None responded.

Bryson has the admirable capacity to dwell comfortably with uncertainty, even to rejoice in it. “No one can say why” the seven octillion atoms that make us “have such an urgent desire to be you,” Bryson observes. “Yet somehow when all of these things are brought together, you have life. That is the part that eludes science. I kind of hope it always will.” In a world full of too many easy answers and unempirical shortcuts, Bryson’s merry agnosticism constitutes a welcome form of discipline.

But there’s a tension between the unified materialist vision presented in the book—“Your brain is you”—and the implicit promise of guidance in Bryson’s subtitle, which suggests a duality between the body and its inhabitant. It’s a duality as knotted as any in the history of philosophy, and its presence in Bryson’s title raises the subtle expectation that he might dispense some wisdom about how to live within this breach. But such wisdom is scarcely on offer, apart from Bryson’s jaunty observation about life at its end: “But it was good while it lasted, wasn’t it?”

“All bodies are compromises between strength and mobility,” Bryson tells us at one point. He is describing the musculoskeletal system, but the observation applies in a sense to his own authorial project as well. If Bryson favors agility here, it is for the benefit of the general reader who will find in The Body marvelously fact-saturated pages filtered through the sieve of an elegant and witty intellect. Experts will hunger for more, but Bryson’s distinctive voice will likely delight readers eager to go sightseeing around the world they embody.