Though he never won the Oscar for Best Director in his lifetime, Alfred Hitchcock enjoys an enviable posthumous existence. He may be the most revered of all film directors today. He is my own favorite. Time was, critics condescended to Hitchcock on the grounds that his movies were merely thrillers, and thus either less important or less serious than blockbusters like Ben Hur or message movies like To Kill a Mockingbird. But Hitchcock always used mystery genre conventions to explore themes of deeper significance; he relied on what he called “the MacGuffin,” the merest pretext, as the pivot for a plot involving crime or espionage and ultimately touching on the dialectic of guilt and innocence, good and evil.

Hitchcock was born in London on August 13, 1899 (and when the 13th of August falls on a Friday, freaky things do happen). He made films for nearly two decades in Britain before moving to Hollywood in 1939, on the eve of World War II. His love for his adopted country shines through in some of his grand settings: the cliffhanger scenes at the Statue of Liberty (Saboteur, 1942), at Mount Rushmore (North by Northwest, 1959), or on the Golden Gate Bridge (Vertigo, 1958). But we also have small-town America at its most innocent (Shadow of a Doubt, 1943), the intimate courtyard shared by Greenwich Village bohemians (Rear Window, 1954), a posh London flat (Dial M for Murder, 1954), and a lonely motel on a dark country road in the rain (Psycho, 1960).

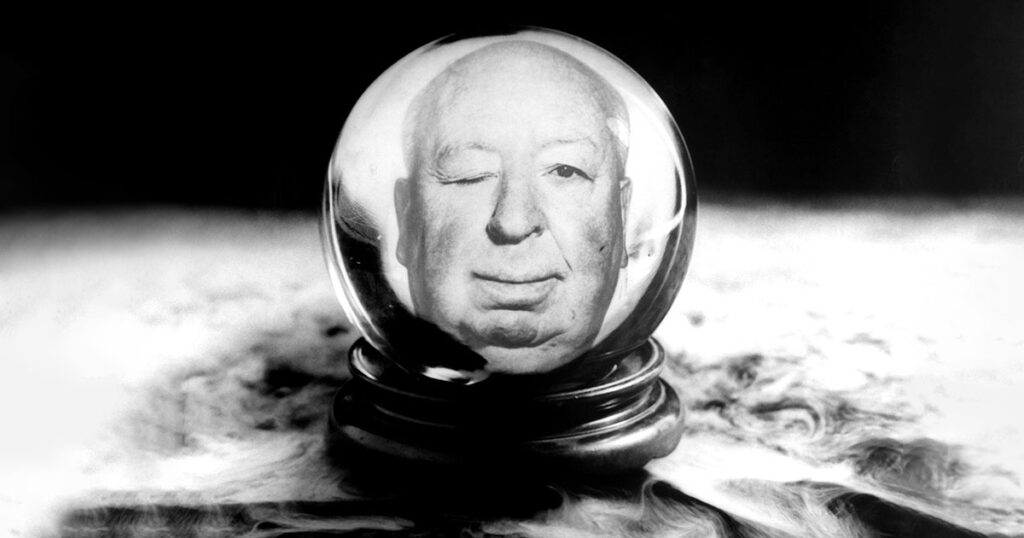

He was prolific; he headlined Cary Grant, James Stewart, Gregory Peck, and a bouquet of beauteous and talented blondes, including Ingrid Bergman, Grace Kelly, Doris Day, Kim Novak, Janet Leigh, and Eva Marie Saint. Understanding his own singularity, Hitchcock signed his pictures with himself in a cameo. He might be the fellow sitting next to Cary Grant on the bus (To Catch a Thief, 1955), a musician carrying a violin case (Spellbound, 1945), or a passenger struggling with a double bass (Strangers on a Train, 1951). In Lifeboat (1944), in which all the action takes place on a small craft and is limited to the few survivors of a shipwreck, the master makes his appearance as the heavyset fellow in a newspaper ad for weight reduction.

I have named eleven of my favorite Hitchcock movies in this piece and yet have not even mentioned Notorious (1946) or The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), about either of which I would write a prose poem. That’s for later. For now, here’s a quiz I’ve devised that will appeal to aficionados or newcomers alike. Hover your cursor over the black box (or tap, on mobile) to reveal the answer.

1. In The Man Who Knew Too Much, who—or what—is Ambrose Chapel?

(A) Albert Hall’s younger brother

(B) The kidnapper

(C) A London church

(D) The “MacGuffin”

(E) A taxidermist

Answer: (C) a London church in the 1956 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much—but metaphorically, it is also (A) an anticipation of the film’s climactic scene at the Royal Albert Hall. Like Albert Hall, Ambrose Chapel is a name that can be taken to refer to a person, the way Dr. Benjamin McKenna (James Stewart) and his wife, the celebrated singer Josephine Conway (Doris Day), interpret it at first. (E) is the very epitome of a red herring, the completely innocent namesake Dr. McKenna tracks down. While (B) is incorrect, it is at least relevant, because the kidnapper is Ambrose Chapel’s main man of the cloth. As for (D), you know what a MacGuffin is, don’t you? Well, here’s Hitchcock’s explanation: “It might be a Scottish name, taken from a story about two men on a train. One man says, ‘What’s that package up there in the baggage rack?’ And the other answers, ‘Oh, that’s a MacGuffin.’ The first one asks, ‘What’s a MacGuffin?’ ‘Well,’ the other man says, ‘it’s an apparatus for trapping lions in the Scottish Highlands.’ The first man says, ‘But there are no lions in the Scottish Highlands,’ and the other one answers, ‘Well then, that’s no MacGuffin!’ So you see that a MacGuffin is actually nothing at all.”

2) Which of these objects did Hitchcock invest with uncanny significance, and what does that tell you?

(A) A glass of milk

(B) A shattered pair of eyeglasses

(C) A cigarette lighter

(D) The key to the wine cellar

(E) A burning mansion

(F) A giant sequoia in the Muir Woods north of San Francisco

(G) All of the above

Answer: (G) All. The shattered eyeglasses at the amusement park stand for the murdered woman in Strangers on a Train. In the same film, the innocent tennis player’s cigarette lighter, given to him by his wife, is the incriminating piece of evidence that the villain wants to plant at the murder scene. In Notorious, the purloined key to the wine cellar leads not only to bottled Nazi secrets but also to the unmasking of Ingrid Bergman as an American spy. (A key is also, well, key in Dial M for Murder.) You might say that the glass of milk in Suspicion, like the coffee cup and saucer in Notorious, accentuates Lina McLaidlaw’s (Joan Fontaine’s) menaced vulnerability. Both homely domestic vessels contain lethal doses of poison. The threat of murder can be disguised in the least threatening of objects; there may be poison in the milk or coffee. There is something eerie and unsettling about the giant redwood in Vertigo and the conflagration at the end of Rebecca.

3) Which of the following is not an authentic Hitchcock moment?

(A) Grace Kelly’s Lisa Fremont cozies up with Harper’s Bazaar while her beau, nursing a broken leg, takes a nap

(B) Grace Kelly’s Frances Stevens offers her beau his choice of “a leg or a breast” as they picnic on chicken on the French Riviera

(C) With one exception, everyone watching a tennis match moves his or her head as the movement of the ball dictates

(D) Doris Day’s Jo Conway belts out “Que Sera, Sera” at a posh party peopled by diplomats in London

(E) Priscilla Lane’s Patricia Martin quotes Emma Lazarus’s poem “The New Colossus” while confronting the villain at the top of the Statue of Liberty

(F) None of the above

Answer: (F) None of the above. Each moment is echt Hitchcock. The movies are, in order, Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, Strangers on a Train, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and Saboteur.

4) In Vertigo, who is real?

(A) Judy, the shopgirl whom Gavin Elster hires to impersonate his wife (Kim Novak)

(B) Madeleine, Gavin Elster’s wife (Kim Novak)

(C) Johnny, first name of Ferguson, the James Stewart character, a retired detective with acrophobia,

(D) Scottie, Ferguson’s nickname

(E) Midge, the fashion designer played by Barbara Bel Geddes

Answer: (E). Midge designs brassieres and has a robust sense of humor, which she displays by painting herself, eyeglasses and all, in the dress and necklace worn by Carlotta Valdes in the portrait to which Madeleine pays homage. Like the fool in King Lear, who disappears in Act III, Scene 6, Midge vanishes after a failed effort to revive her boyfriend in the sanatorium. Everything that happens from that point on is as unreal as an opium dream or a fantasy. Neither Johnny nor Scottie knows who he is. Judy thinks she is real, but the midwestern girl is real only when playing the part of upper-class Madeleine. “You were a very apt pupil,” Scottie says in a climactic moment. “Well, why did you pick on me? Why me?”

5) Match the quote with the movie it’s in:

(A) “We’ve become a race of Peeping Toms. What people ought to do is get outside their own house and look in for a change.”

(B) “You Freud, me Jane?”

(C) “Oh, you are a fine one to talk! You have a guilt complex and amnesia, and you don’t know if you are coming or going from somewhere, but Freud is hooey! This you know! Hmph! Wise guy.”

(D) “Pat, don’t tell me about my duty. It makes you sound so stuffy. Besides, I have my own ideas about my duties as a citizen. They sometimes involve disregarding the law.”

(E) “Don’t forget. Bob’s your uncle.”

Answer: (A) Rear Window, (B) Marnie, (C) Spellbound, (D) Saboteur, (E) Frenzy

6) Can you make the case that Shadow of a Doubt is Hitchcock’s most patriotically American movie?

(A) Yes, because it celebrates the small town of Santa Rosa, California, as the good-natured, optimistic, democratic, innocent heart of America.

(B) No, because Saboteur ends with the Statue of Liberty, and you can’t get more pro-America than that.

(C) No, because Cary Grant lifting Eva Marie Saint to safety atop Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest is an allegory of the American dream.

(D) Maybe, but the important point has to do with identity. Both Teresa Wright and Joseph Cotten are named Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt. He is her charming uncle, her favorite, and she alone in the family comes to recognize that he is the Merry Waltz murderer.

(E) Maybe, because Henry Morgan and Hume Cronyn in Shadow of a Doubt are blissfully oblivious to the danger near them and even divert themselves by concocting methods of committing the perfect murder. They embody the American mind.

Answer: I would argue for (A), though the comic subplot of (E) is strong evidence of America’s addiction to ignorance-as-bliss, and the identification of Teresa Wright with her uncle (d) proves that in a Hitchcock movie, the MacGuffin is to plot what psyche is to drama.