Not all that long ago, the long-playing vinyl record was very nearly extinct. The road to obsolescence was always going to be short—what the compact disc started in the 1980s, the MP3 was bound finish two decades later. And yet, something strange has been happening of late, at a time when we have surrendered so much of our lives to the tyranny of the digital: vinyl has come back. In 2006, only 900,000 LPs were sold in the United States, yet as Bill McKibben writes in a recent issue of The New York Review of Books, that number grew to 12 million in 2015. In Great Britain, vinyl sales have increased for nine straight years, with 3.2 million albums sold in 2016, the biggest total in 25 years, topping digital purchases for the first time. In a culture where just about anything can be downloaded, streamed, or—let’s not forget—stolen, this state of affairs isn’t just commendable. It is a lovely, noble act of defiance.

So many wonderful recordings have been newly pressed and reissued, and though I have purchased far more than I can reasonably afford (in the classical music business, new vinyl is exorbitantly priced), the bulk of my collection consists of used albums. About a decade ago, I started buying LPs on eBay, often in large lots—50 Deutsche Grammophon records, 75 old Decca Classics, 30 concerto recordings by the great violinists of yesteryear. For a period of a few months, the boxes would arrive nearly every day. Once, when I happened to be home on a weekday, I ran into the postman, who asked, not without suspicion, if I was running some sort of business out of the townhouse my wife and I were renting. “No, no, I’m just buying records,” I said. “Oh!” he said. And then, I detected the slightest frown. “That’s a lot of records,” he said. It couldn’t have been much fun for him, I realized only then, lugging those boxes from his mail truck to my front door so many times a week.

Audiophiles have always maintained that vinyl sounds warmer, has more presence, than CDs. I don’t know. I’m not an audiophile. I listen to LPs, CDs, and digital downloads in equal measure, and though I don’t think I fetishize vinyl as some quaint artifact of my childhood, I do agree that a far greater tactile pleasure is involved in listening to an LP. A record demands interaction, after all; you can’t put one on and simply drift away. You have to change sides after 20 minutes or so, forcing you to activate muscle memory that likely went dormant with the advent of iTunes, to say nothing of the six-disc CD changer. Apparently, this isn’t a generational thing. In other genres of music, vinyl is largely the province of millennials—the Moleskine notebook brigade that came of age in a digital world but now yearns for what McKibben calls the “tangibility of the actual physical platter,” the “palpable sense of ritual.”

It isn’t just the record itself you interact with. When I was young, I would sprawl out on our living room floor, obsessively poring over the liner notes on the backs of record jackets, as some Mendelssohn symphony or Schubert string quartet played in the background. I received a whole education by reading those jackets, as well as the booklets contained inside box sets. I imagine some people have no problem downloading liner notes and librettos onto their phones, or squinting at the tiny booklets crammed into the jewel case of a CD. But that is not for me.

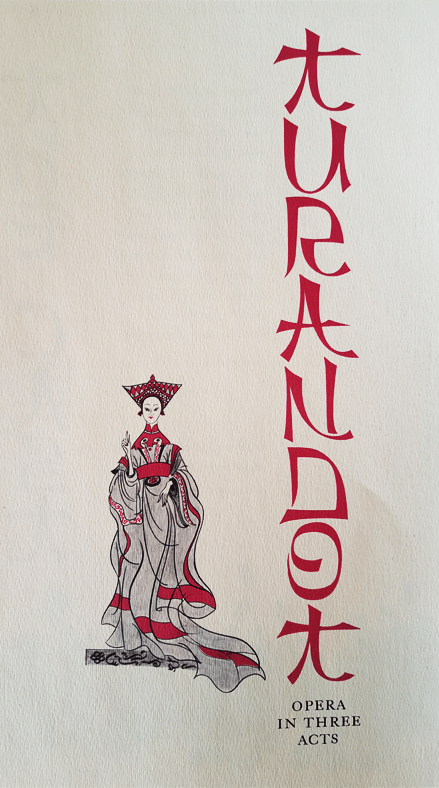

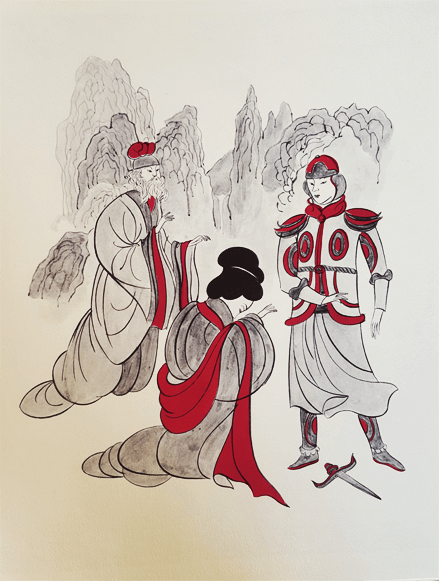

I have before me one of those box sets: a recording of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Turandot, with Erich Leinsdorf conducting the Rome Opera House Orchestra and Chorus, and a cast featuring Birgit Nilsson, Jussi Bjoeling, Renata Tebaldi, and Giorgio Tozzi. The performance itself is unimpeachable, but it’s the booklet I want to praise here—about one foot by one foot in size, with some 40 pages of creamy, heavy-stock paper. Inside are numerous photographs, not only headshots of the cast but also images of the musicians at work, both on stage and in the studio during playback sessions. In such a large format, the libretto is most readable, the eye easily flitting between the Italian and English texts side by side on the page. Two lengthy essays are included, as well, so detailed and illuminating in their discussion of Puccini’s opera that to call them mere synopses would be an injustice. The elegant typography and many illustrations—evocative, full-page, pen-and-ink drawings shot through with streaks of vibrant magenta—immerse the reader in Turandot’s realm of ancient Peking, a world of priests, princesses, and grand processions. All the opera’s characters are depicted in these drawings: callous Turandot, wise Timur, penitent Liù, brave Calaf, full of concern for the fate of his loved ones.

It’s a meaty guide, this book—and a work of art, too, a beautiful object to hold in your hands and flip through and read. Where else but inside a vinyl box set could you find such a delightful thing?

Take a peek at the liner notes from the 1960 recording of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Turandot, illustrated by Joyce Behr.