For the longest time, especially when traveling, I kept a journal, filling in the pages of spiral-bound notebooks covered in blue-and-white or green-and-white cardboard. These proved a bounty when I began to write for a living. I could glean from them long-forgotten but useful (for writing purposes) details from trips I made 10, 20, and now I can say, with some bafflement, even more than 30 years ago. As time passed, I would occasionally pore over them in search of my former self—a naïve, romantic young man determined to set out abroad, script his own life, never submit to convention, and savor the now. A young man whose appetite for wonder would be difficult to sate. Could the world have once seemed so grand and surprising to me?

I’ve now reached middle age, and I’ve managed to live my dream, living abroad and traveling to dozens of countries, mostly funded by magazines for which I’ve written or in the course of researching my books. But my journals have lost their hold on me. I discovered this quite recently, when I mislaid the first one I ever kept as a voyageur. I shrugged. Why would I need it now? I don’t require any supporting texts to conjure memories from my travels. In my mind, I can re-create vivid vignettes from times spent all over the world. This mental magic lantern is my private treasure, the most valuable thing I possess. As an atheist who believes in no divinely ordained purpose to life, I see the point of existence as the accumulation (without causing harm to others) of experiences, of both the natural and the human world. No “bucket list” for me. I’ve lived it.

These wayfaring remembrances are nothing less than who I am; I would not be me without them. One of my earliest recollections from childhood is of a road trip. I see myself as a scared little boy, huddled in the back seat of his parents’ boxy 1960s Oldsmobile, en route to Ocean City, Maryland, looking out into the autumnal night sky. AM radio signals crackle in and out, bringing news of what then seemed to me impossibly faraway lands—Ohio, Michigan, Arkansas. I was often afraid of car travel, and distracted myself by imagining, in the dark, the exotic neighborhoods of Cleveland, the bizarre byways of Detroit, the alluringly alien precincts of Indianapolis. From then on, I’ve been drawn to the melancholy—to the moon silvering the stony, sweeping steppes of eastern Anatolia, to the nocturnal winds soughing through the palms on Curaçao’s westernmost cape, to the waves of the Indian Ocean breaking in the night over the white sands of Oman’s southern coast. Visiting these places has changed me.

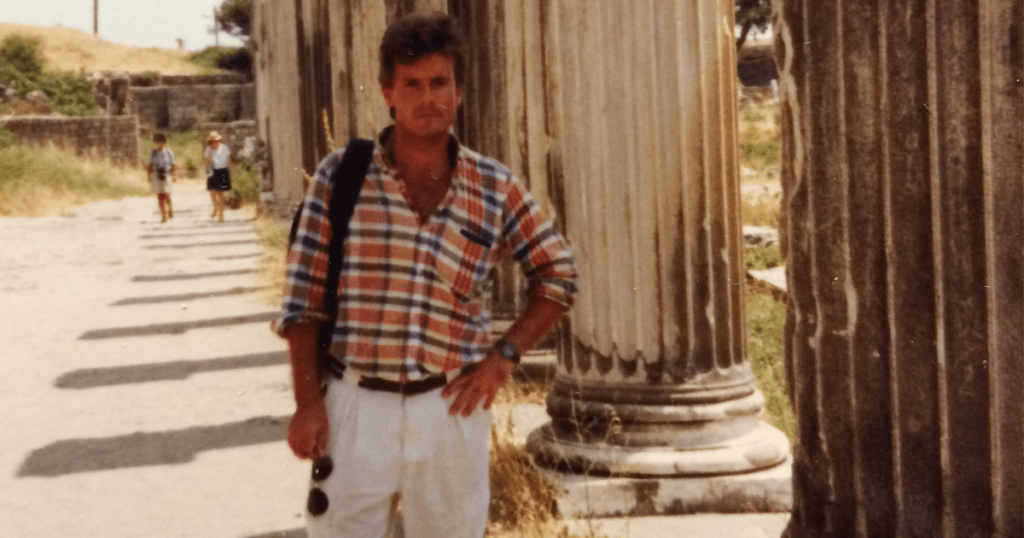

But just as often, I have been entranced by light. I open my eyes, awakening to salty Aegean breezes wafting in through my open window, to the glow cast on the wall by the rising sun. I’m on the island of Paros, in the Cyclades, sometime in the mid-1980s. My room is a Spartan whitewashed chamber atop a grocery store, with a sand-speckled floor and a single starched sheet on a mattress as bedding. (Summer temperatures rarely drop enough there to require more.) I rise and look out onto the azure-domed churches, the thatched-roof windmills, the pale blue wash of the sea with dark islands looming on the horizon. The mists gradually lift to reveal a brilliant vista. It is no cliché to speak of the glory of Grecian light, the radiance of the sun that once warmed agoras and temples and stoas, the sources of Western civilization.

Elsewhere, light has been a burden, even an enemy. I see myself one evening in 2000, lying inside my tent in Morocco’s Anti-Atlas Mountains, marveling at the pattering of rain on the yellow nylon walls. Outside are argan trees, three braying Arabian camels, and my two exhausted Bedouin guides. The cool, the clouds, even the foliage in the grove give succor to us all. The scorching trials of the desert have receded, and only windswept passes, mesas, and the ocean lie ahead. For three grueling months, while gathering material for my third book, Glory in a Camel’s Eye, I have been trekking down the Draa Valley in the Saharan badlands of southernmost Morocco—months that have almost undone me with dehydration, nausea, and dizziness. But in the mountains, the climate has shifted unexpectedly from desert to moderate. I step outside to luxuriate in the cool, to hold my face to the rain—a podarok sud’by (“gift of fate”), as Russians would say. Within a week we will reach our terminus, the Atlantic coast, just north of Tan-Tan, and stare out into the ocean, mesmerized by the waves, the screaming gulls. The agony has passed, deliverance is near.

This memory melds into another, primal one. I’m staring again out into empty maritime expanses, into a gray sea and a limpid sky, but it’s 30 years earlier. I’m on the beach at Ocean City, overcome with wonder, and asking my father what country is across the water. “Portugal,” he replies. “Or maybe Morocco.” Morocco! How exotic it sounds!

The alien has always stirred me. It is November 1983. I huddle under my overcoat, a heavy scarf around my neck, as my train chugs south through the Carpathians, with moonlight glinting in frozen puddles beside the tracks, and coarse-knuckled peasant men and women, bundled up and sullen, eyeing me suspiciously from seats opposite mine. I see the belfries and steeples of Sighişoara’s churches, and the unlit streets below blanketed in snow. I see the long lines in front of food stores, I smell the alcohol on the breaths of passersby, I wipe the coal soot off my cheeks. Nicolae Ceausescu’s Romania, brutal, impoverished, and isolated.

A month later, I see a rickety Bulgarian train from sooty, still-socialist Plovdiv weaving its way out of the snowy Rhodope Mountains, crossing the bare plains of Turkish Thrace, and pulling, in the evening, into Istanbul, a mélange of color and light, of hawking vendors and begging children and honking taxis, with the Allahu akbar! of the call to prayer—something I have never heard before—rising over the din of the traffic. Soon, I stand marveling at the play of the street lamp light on the Golden Horn’s black currents. But as I stroll through the city that night, I cannot relax. A military coup has taken place a few years before, tanks are stationed on Taksim Square, and helmeted soldiers in armored personnel carriers rumble down the almost deserted streets. One stops, and an officer jumps out to ask for my papers. Fierce-browed, but smiling and polite, he tells me to return to my hotel, seeming more concerned for my safety than anything else. It never occurs to me that I could have been shot or arrested, if only by mistake.

A year earlier, I hear the steam hiss in the night as brakes are released, the metallic creaking of the couplers, and the dull roar of wheels rolling over rails as my train crosses the Greek border near Florina into socialist Yugoslavia’s Macedonia; the next morning, I see the waters of Lake Ohrid, still and green, beneath the peaks of Albania—in 1982, a country still completely closed off from the world, suffering under the vicious Enver Hoxha communist dictatorship. I listen to myself talking to a young Yugoslav of Albanian origin who has accosted me by the waterside: in addition to his mother tongue, he says, he speaks Serbian, Macedonian, Turkish, and English. Later, in Kosovo, I see

donkey-drawn carts in the mud, veiled women, skull-capped men, and minarets. Curious children and angry adults, both Serbs and Albanians, are what I remember most. I am at once in Europe and decidedly not. Something bad will happen here, I think.

Fear seizes me more than once during my peregrinations, especially after I move to Russia. It is 1993. I watch the scraggly trees shrink as the truck on which I’ve hitched a ride grinds up stony passes along the Kolyma Route, heading toward Yakutsk, into the tableau of death and desolation that was, during the Stalin decades, gulag land. I see chasms beneath us, frozen rivers, and I hear the wheels slipping on the ice, my driver grunting as he struggles to keep control.

Months later, with an 8,325-mile trip across Russia and Ukraine behind me, I settle into an apartment in Moscow to write my first book, Siberian Dawn, while the city undergoes a harrowing transformation from a Soviet state to something new and unknown. On a sunny October morning, I am standing on the banks of the Moscow River. I have just seen Yeltsin’s tanks thundering down the Arbat, soldiers sitting atop them, their rifles at the ready. I feel the concussive shock waves as the tanks open fire on the Supreme Soviet; I cringe, duck, and run with the crowd from gunfire raining down from rooftops. I see the paint-chipped walls of my one-room apartment, the zebra-trunked birches outside my picture window and the blazing orange leaves behind them. At night, I hear automatic weapons firing from near the police checkpoint a few blocks away, where officers are attempting to impose a curfew in support of Yeltsin’s efforts to suppress the rebellion. Fear, gunshots, screaming, fear, sleepless nights, and more fear.

But three years later, in environs that could not be more different from those of Russia, fear loses its hold on me. For my second book, Facing the Congo, I take a cargo barge from Kinshasa 1,100 miles up the Congo River, deep into the heart of tribal Zaire. The barge’s owner, a boisterous, gimlet-eyed colonel from Mobutu’s secret services, graciously allows me to pitch my mosquito net atop his cabin on the pusher-boat, where I could be alone, separated from the hundreds of impoverished passengers huddled fully exposed to the elements on the craft’s main deck. But I’m nonetheless paralyzed, even nauseated, with anxiety, dreading arrival in Kisangani, where I plan to start canoeing back downriver, alone, to Kinshasa. Relief comes at nightfall, when at the height of my despair, I gaze out into the heavens, where a meteor shower streaks across the night sky against a backdrop of brilliant stars. Never have I seen such a clear sky—typical of the Equator, I soon discover. Contemplating its splendor, night after night, alone on the rooftop, I come to truly comprehend a consoling truth: the Earth is a speck of dust floating in a cavernous universe; and I, on that speck, merely a tiny fleck, with an equally tiny fate. With that realization, my troubles, my fears about the dangers ahead begin to abate. They soon return full-force once I begin paddling down the huge river with my guide from the Lokele people. (The colonel has persuaded me that going it alone would be tantamount to suicide.) But I emerge from those months transformed. Nothing I do later will ever frighten me as much again.

When I arrive back in Moscow, I fight the urge to drop down and kiss the soil. I am beginning to feel at home here, a city that carries an outsize reputation as a dark, shady, and dangerous place. But compared to Zaire, it has, at least for me, become a haven.

More than a decade later, and a few years after my mother’s sudden death, I am flying to Bogotá, the city in which she spent the happiest years of her life. She had always wanted me to go there, but during her lifetime I never did. Now, researching a biography, I am following the life-route of Simón Bolívar. The fate of this tireless, romantic 19th-century revolutionary and statesman, who freed five countries from Spanish rule and covered more miles on horseback than Alexander the Great, moves me to re-create the wanderings of his two-decade campaign of liberation.

Before my plane begins its descent into Bogotá, in my mind’s eye I see the Colombian oil painting hanging on my mother’s living-room wall: verdant mountains lathered in fog, crisscrossed in their lower reaches by an ascending dirt road; the rain-soaked stone churches and belfries of the historic center. This is exactly the vision before me as I drive into town. The soft manners and sympathetic eyes of the Colombians bespeak the Latin kindness my mother always missed back in the States. Her loneliness in the States, her wistful talk of Bogotá, first set my imagination wandering abroad, as if I were destined to discover my home somewhere else.

From Caracas and Bogotá, Bolívar led his army south, so that’s where I go. I see black Ecuadoran volcanoes, their summits lost in thunderclouds. I see myself gasping for breath in Puno, at an altitude of almost 13,000 feet, on the Peruvian flank of Lake Titicaca. All night, barrages of rain batter my window. I see myself in my frigid hotel room, sleeping fitfully beneath insufficient blankets, my breath puffing white in the pale light from the street lamps outside.

I see myself the next morning, aboard a minibus to the Bolivian border, as I trundle down the grassy Altiplano plateau in the company of Aymara-speaking indigenes. As the road rises ever higher, the grass yellows, here and there dotted with clumps of ichu and tola shrub. Cloud shadows trail across the plain and over the treeless hills beyond. Indian cowherds and men in black fedoras, their shoulders draped with red-brown ruanas, lean on canes outside their mud huts. Their wizened faces and shrunken builds tell of a wretched life in tough terrain, where, during the winters of June through August, nighttime temperatures drop to minus 12 degrees Fahrenheit. Few places are more alien, and alienating, than the Altiplano.

I needed to experience the Altiplano, and Zaire, and everywhere else I’ve traveled; I needed to live through them. Reminiscences from these trips make me realize that I’m comfortable living in many places, but not in every place. In Moscow, I have indeed found my home. It’s not only where my wife is, but also where I do my best writing. It’s the capital of the land that, in fact, made me a writer.

Shortly after my return from the Altiplano, I see myself with Tatyana, my wife, huddling on a winter night beneath blankets at a table outside at a café, on the Promenade des Anglais, Nice’s historic waterfront. (The same waterfront saw a horrific terrorist attack on Bastille Day, two summers ago. I happened to be in Nice that night, in a hotel nearby, but luckily had decided to stay in.) We’re the only ones not to take seats inside. The storm coming off the Mediterranean thrashes the palms, batters the sea, drives away strollers. The beach ahead is empty, the streets deserted.

Above I see no stars, of course. But the lessons the stars taught me on the Congo remain with me still, and the storm-churned sea, in its own way, howls of the beyond. My memories, the ones unpublished, in any case, will last as long as I do. And then, one day, they, with me, will vanish into the void.