Indefensible Torture, Unfree Speech

What Censorship Kept America from Learning about the Futility of “Enhanced Interrogation Techniques”

The Black Banners Declassified: How Torture Derailed the War on Terror after 9/11 by Ali Soufan with Daniel Freedman; Norton, 594 pp., $17.95

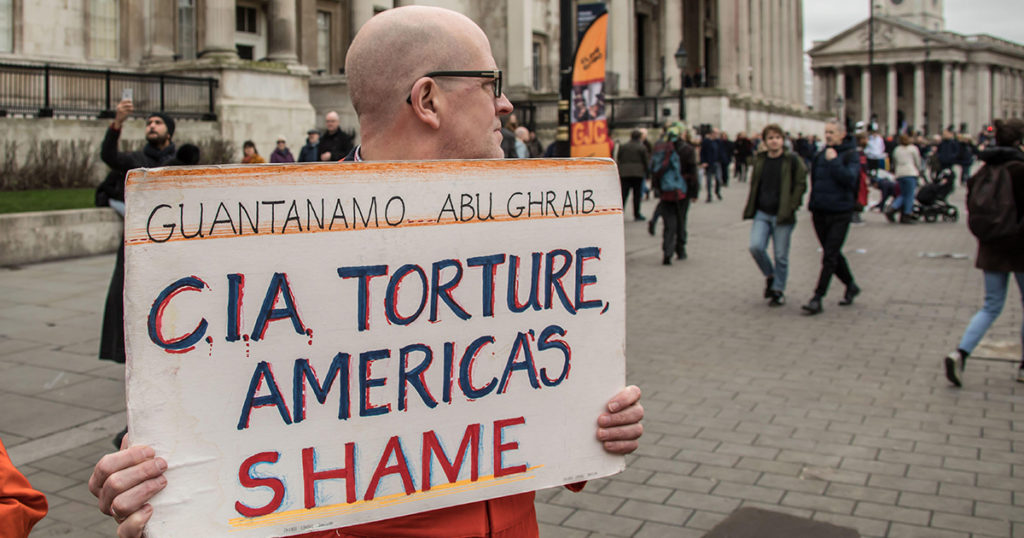

Did torture by the United States government of captured enemies yield valuable intelligence in the war on terror during the George W. Bush administration, as the government claimed? Or was it largely ineffective, endangering national security by failing to get the kind of information that lawful interrogation had been getting? And because torture is illegal in the United States, in all places, at all times, including its use in wartime by the military and intelligence agencies, did the CIA’s employment of it undermine the rule of law?

As recently as January 2017, the Pew Research Center found that 49 percent of Americans polled said there are no circumstances when torture is acceptable; 48 percent said there are some. Ali Soufan, who was an FBI special agent from 1997 to 2005, is an expert in the best way to get a prisoner to tell the truth in an interrogation. In 2011, he and Daniel Freedman wrote The Black Banners: The Inside Story of 9/11 and the War Against Al-Qaeda to explain why the 48 percent were wrong—why the United States cannot justify the use of torture under any circumstances.

As a result of the CIA’s censorship, however, the nation learned less from the book than Soufan knew and was eager to tell. Central to his story was a decisive interrogation that Soufan and others conducted soon after 9/11 of Zayn al-Abidin Muhammad Husayn Abu Zubaydah, the first “high-value” detainee in the war on terror, a Palestinian raised in Saudi Arabia who, though not a member of al-Qaeda, became a jihadist against the West—what The New York Times called “a sort of travel agent, camp administrator and facilitator for militant fighters in Afghanistan in the early 1990s.” Only three of 63 pages of the book describing this interrogation had no blacked-out words, sentences, or paragraphs. The CIA required redactions throughout. On some pages, the censors blacked out every word.

The effect was to move the reader from a seat revealingly close to the action to one with a partially blocked view. The uncertainty the redactions introduced about the essential details of the story hovered over the rest of the book, casting doubt on its revelations.

This prepublication government censorship applies to millions of former intelligence agency employees and military personnel with access to classified, or secret, information. As the legal scholars Jack Goldsmith and Oona Hathaway wrote on the Lawfare blog and in The Washington Post in 2015, the process of review is often “cumbersome, time-consuming, and seemingly arbitrary” and, through censorship of writing like Soufan’s, “results in pervasive and unjustifiable harms to freedom of speech.”

In 2018, the journalist Raymond Bonner and the filmmaker Alex Gibney wanted to interview Soufan for a documentary they are making about whether torture —what the CIA calls “enhanced interrogation techniques”—is effective as a method of interrogation. They sued the CIA in federal court, asserting in their complaint that the agency had permitted the publication of books using the same materials censored from Soufan’s book in order to “portray the CIA’s use of EITs [torture] as ethically and legally justifiable, highly effective, and successful in obtaining actionable intelligence.”

The discrimination against Soufan’s point of view was a classic violation of free speech under the Constitution’s First Amendment. The government re-reviewed Soufan’s book because of the lawsuit, approving removal of most redactions, which permitted Soufan to speak on the record about this newly unredacted material with Bonner and Gibney. Now Soufan has published The Black Banners Declassified “to help stave off any temptations to return to techniques that produce nothing of value, help terrorists recruit more followers, and make all Americans less safe.”

With this new edition, we can see even more clearly that the interrogation of Abu Zubaydah is a case study in the comparative effectiveness of interrogation techniques. In March 2002, Soufan began his interrogation using rapport-building, which employs knowledge of a person’s history, culture, mindset, and vulnerabilities to outwit him into cooperating. Soufan, who was himself only 31 at the time, was one of the few FBI agents who spoke Arabic, having grown up in Lebanon and immigrated to the United States when he was 16.

Abu Zubaydah had been shot in the thigh, groin, and stomach while trying to escape across a rooftop from a raid in Pakistan, where he was captured in 2002. A bullet in his thigh shattered coins in his pocket, and as Soufan wrote, “Some of this freak shrapnel entered his abdomen.” Soufan and his team did their best to turn the “very primitive location” of the black site in Thailand where they would do the interrogation into “a makeshift hospital room.” When Abu Zubaydah arrived, Soufan wrote, “He was barely moving. Parts of his body were bandaged up, and elsewhere he had cuts and bruises. He was in critical condition.”

Soufan stayed the first night on a cot in a room next to Abu Zubaydah’s. Around 3 a.m., a medic asked, “Hey, Ali, how important is this guy?” Soufan replied, “He’s pretty important.” The medic said, “Well, if you want anything from him you’d better go and interview him now.” Abu Zubaydah was septic, with infection poisoning his internal organs. Without extensive medical help, he was likely to die soon. The only chance he had to live was if he was treated at a real hospital. Because “he was no use to us dead,” they got him hospitalized.

Abu Zubaydah had a breathing tube and couldn’t talk, so Soufan resumed the interrogation by having him point to letters on an Arabic alphabet chart to form words and provide information. At first, Soufan concentrated on getting “more details on pending threats and to see what information” Abu Zubaydah could give on Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda’s senior leadership. During one interrogation session in the hospital’s ICU, Abu Zubaydah identified Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, or KSM, from the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists list. He was later identified as “the principal architect of the 9/11 attacks.” Abu Zubaydah disclosed that KSM had trained the 9/11 hijackers, spoke English fluently, and was responsible for all al-Qaeda operations outside Afghanistan. Soufan wrote, “The U.S. intelligence community until now had had no idea that KSM was even a member of al-Qaeda (he was believed to be an independent terrorist), let alone the mastermind of the 9/11 attacks.” Soufan’s interrogation of Abu Zubaydah led to the thwarting of two other terrorist attacks.

Soon after this revelation, however, a group from the CIA arrived, with a mandate “to do something new with the interrogation” because “Washington feels that Abu Zubaydah knows much more than he’s telling you, and Boris here has a method that will get that information more quickly.” Soufan didn’t identify Boris in the redacted edition and, oddly, doesn’t do so here either. Boris is James Mitchell, the CIA contractor who helped devise and oversee the agency’s program of torture, which used cruelty and humiliation to try to make victims talk. Abu Zubaydah was his first subject.

Mitchell boasted, Soufan wrote, “that he would force Abu Zubaydah into submission. His idea was to make Abu Zubaydah see his interrogator as a god who controls his suffering,” first by taking away his clothes and then, “if he failed to cooperate,” by using “harsher and harsher techniques,” until the interrogation made him “buckle and become compliant.” Soufan said to Mitchell, “Don’t you realize that if you try to humiliate him, you’re just reinforcing what he expects us to do and what he’s trained to resist?” Boris replied, “You’ll see.” For days, Soufan watched as Mitchell’s interrogation failed completely: “Nothing was gained through techniques that no reputable interrogator would even think of using.”

So far, Soufan wrote, Mitchell was using “borderline torture.” Then the interrogation began “stepping over the line … . Way over the line.” Soufan called FBI headquarters, described the escalation, and said that he could “no longer remain here. Either I leave or I’ll arrest him,” meaning Mitchell. “Beyond the immorality and un-American nature of these techniques,” Soufan recounted, he couldn’t stand by as Mitchell “abused someone instead of gaining intelligence that would save American lives.” The FBI told Soufan to leave, saying about the abuse: “We don’t do that.”

In 2014, the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence recounted in an unclassified version of a report on torture what happened to Abu Zubaydah after Soufan left. He was held in isolation in intense cold for 47 days, and then interrogated with enhanced techniques for 20 days, 17 in a row without any break in the torture. For 24 hours a day, the CIA interrogated him, using in various combinations the techniques of what the Senate report called “walling, attention grasps, slapping, facial hold, stress positions, cramped confinement, white noise and sleep deprivation.”

The CIA waterboarded him 83 times during the month of August 2002. It did so two, three, or four times a day, “with multiple iterations of the watering cycle during each application.” Waterboarding often resulted in his “hysterical pleas” for mercy and in one session, he “became completely unresponsive, with bubbles rising through his open, full mouth.” The report went on, “According to CIA records, Abu Zubaydah remained unresponsive until medical intervention, when he regained consciousness and expelled ‘copious amounts of fluid.’” He almost died.

The CIA videotaped these interrogations, 92 tapes in all, but in 2005, the agency destroyed the tapes—in violation of a federal court order to retain them. By Soufan’s account, the tapes would have shown why the torture failed: it aimed at getting Abu Zubaydah to comply rather than cooperate (“you get someone to say what he thinks you’ll be happy hearing, not necessarily the truth”). Rather than using cunning to get information, as Soufan did, the torture strengthened Abu Zubaydah’s resistance by giving him “a greater sense of control.”

In 2019, Abu Zubaydah made drawings of himself being tortured, including being waterboarded—“brutal and far worse than the C.I.A. represented,” the Senate Select Committee judged. The drawings are detailed and grim and appear in a report called “How America Tortures.” He is now, as one of his lawyers described, “immured in a top-secret military prison.” His lawyers have urged the government to charge and prosecute him or release him, but, the lawyer wrote, “the U.S. government doesn’t want to prosecute him”—because it doesn’t want to “take the risk that all the grisly details about what the United States did to Abu Zubaydah would emerge during a trial.”

So, after 18 years, “the United States continues to hold Abu Zubaydah in solitary confinement, incommunicado, in that military prison, as a ‘forever prisoner.’”

There is no doubt, the Senate Select Committee report concluded, that his CIA interrogators tortured him, as the treatment is defined by U.S. law and the United Nations treaty it incorporates. The committee found that the “CIA marginalized and ignored numerous internal critiques, criticisms, and objections concerning the operation and management” of its detention and interrogation program, including those of Soufan.

The report about torture cites Abu Zubaydah more than a thousand times. Still, he was only one of dozens of people the CIA tortured before January 2009, when the Obama administration ended the program. The CIA had subjected 39 people to enhanced interrogation—at least 17 without authorization from CIA headquarters.

With Soufan’s crucial viewpoint censored, American understanding of its interrogation program was indefensibly incomplete. Black Banners Declassified arrives too late to have influenced American opinion when memories were fresher and the country was focused on the torture question, before the turmoil of the Trump years blurred the brutal details of that chapter. As history, however, the book is enormously impressive and valuable: it speaks truth to power with dignity, precision, and the vigor of forever-damning facts.