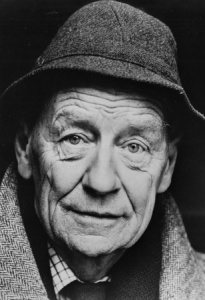

William Trevor, who died on November 20,is conventionally and conveniently thought of as an Anglo-Irish writer. But to consider him in that way is less to apply the finality of a category than to initiate an exploration of the distinctive significance of his work. It’s true that, in a literal sense, Trevor was Anglo-Irish. Born William Trevor Cox in 1928 in Mitchelstown, County Cork, he was reared and educated in Ireland. But his adult life was spent in England, first in London, then in Devon. Yet, the hybrid identity that the Anglo-Irish label typically brings to mind, together with its divisions and fidelities, is only one of many contexts featured in the body of work produced during the 50 years of Trevor’s prolific career.

To the contrary, indeed: one of the noteworthy aspects of his output is that it succeeds in being equally on speaking terms with the author’s place of origin and his place of residence. The hyphen in Anglo-Irish can be interpreted in many ways—as a minus sign, a two-way switch, a lightning conductor, a border crossing, and so on. Uniquely, however, in Trevor’s hands it has the nature of a caesura, a line break, whereby both sides are treated with such scrupulous attention that the ostensibly fixed character of “sides” is not merely dissolved but superseded by something—a quality, an experience, a possibility of virtue—capable of saving each from the other and from itself.

However desirable an author may find such an outcome, he will lose credibility if he merely asserts it. Trevor avoids this pitfall by simply being honest about strangers and strangeness. Not only did he write a novel entitled Other People’s Worlds; his entire output may be regarded as an elaboration of the phrase. And he received a number of lessons in the reality of those worlds growing up in Ireland. There, not only was he not a Catholic in a very self-consciously Catholic polity, he was also not a member of the traditional Anglo-Irish landed class of Protestants but of the provincial Protestant professional class, a minority within a minority. The worlds to which he did not belong had the big historical stories, the confidence of certain slogans, the warrant of authenticity in powerful loyalties. In these, the writer Trevor found much to wonder at, eyebrows raised.

At a different level, his bank-manager father was from the west of Ireland, his mother from the north, and the former’s career meant frequent moves from branch to branch in places comparable to Mitchelstown, market towns of central importance locally but also prone to insularity and small-mindedness. It was not easy to say where home was, and the idea of home also suffered from the deterioration of his parents’ marriage (they became “other people” in Trevor’s arrestingly open portrait of them in his essay “Field of Battle”). The coexistence of—even the involuntary codependence between—love and cruelty in Trevor’s fiction can be read as a reproduction on an intimate plane of the injurious historical entanglements between Irish and Anglo. Not that Trevor would approve of such a reading: for him, as he said, “the relationship between the people comes first.”

Yet, though there was much that young William Trevor Cox stood outside of and was obliged to look in on, this early state of not quite belonging is one he turned to notable advantage as a writer. The spectator-child is the father of the detached narrator, and in his detachment the ethos of Trevor’s writing emerges. His characters’ strangeness—sometimes evident in their names, sometimes in the banality of their language and outlook—is a condition that they are allowed to inhabit. No alternative exists but to acknowledge the freedom and responsibility of doing so, although seeking alternatives is typically what constitutes a Trevor narrative, together with the costs, to self and others, of that pursuit. But Trevor is not interested in strangeness for its own sake. Beneath the surface of his fiction is an engagement with difference, suggested most obviously, perhaps, by how often he gives female characters the lead.

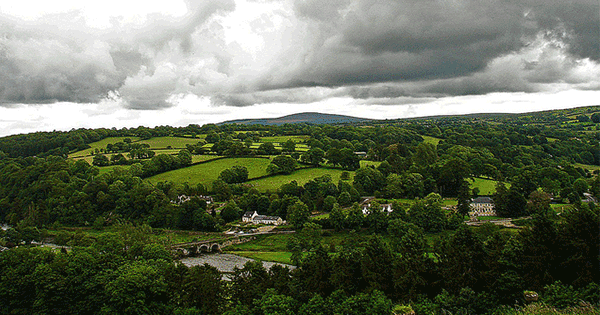

This engagement also, perhaps, has a bearing on how he regards his Anglo and Irish selves; each would do well to acknowledge the other’s inevitable difference—a version of the “parity of esteem” that both communities in Northern Ireland were encouraged to practice. But Trevor’s work provides for a further position, an earned outcome of his detachment and sense of difference. This position is one of tolerance, and if his work does possess an ethos, this is it, a patient teasing out of the possibility of resolution. Such a possibility is not always realized, and is not realized by all of Trevor’s characters. Suffering and evil are very much alive in his imagination—but not to the extent that everything else dies. Hill-walking in the little-known, deserted area of the Nire in County Waterford, Trevor makes no bones about his surroundings—“Nature is defiant on Europe’s western rock.” But even in this deserted upland, the presence of a “wisp of romance” has to be acknowledged, too.