Inside the Burns Unit

How Scotland’s national poet brought solace at a time of pain and isolation

In March 2020, when my family entered quarantine and my world began shrinking, I felt oddly relieved. I’d retired from the English department at Washburn University in 2017, and other than teaching a few short-term courses for learners over 55 and giving a couple of lectures and readings, I had intended to go about the rest of my business as usual—volunteer library work, meetings, lunches with friends, other social obligations. With the onset of the pandemic, however, I erased each of these from my calendar with genuine relief. I began, as I told people, to channel my inner hermit.

And with no “usual,” I turned to the unusual. I had, over the months before, fitfully embarked on a personal project completely new to me: I was memorizing the poetry of Robert Burns, or at least those poems dearest to my grandmother and my father. I had read their travel journals from when they’d visited Scotland years ago on pilgrimages to Burns sites: she in 1960, my father 20 years later. I meant to write about the Scottish diaspora, their part in it and thus my own, through Burns’s poetry and its influence on my family. Now that my work could be constant rather than fitful, I doubled my efforts to commit favorite poems to memory, spending the first mile or two of my early morning walks adding lines to my brain. I wrote glosses of each memorized poem, since knowing them by heart increased my appreciation and understanding of them. My gloss of “Tam O’ Shanter,” that 228-line narrative poem, runs to eight pages.

In late March, my son and his girlfriend, now fiancée, returned from their teaching stint in Bangkok, Thailand, and after quarantining for two weeks, became part of our pod. During dinners, my family indulged my Burns obsession, willing to sit through the 14 minutes of “Tam,” or the much shorter “Lines Written on a Bank Note.” Neighbors in my Topeka, Kansas, neighborhood saw me walking, checking my phone for Burns lines, declaiming the poetry, but they made no comment. I was seriously immersed.

There’s a joke about the Queen of England visiting a Scottish hospital. One ward is filled with patients, none with any obvious sign of disease or injury. When the monarch greets the first bedridden man, he replies, Fair fa’ your honest sonsie face, / Great Chieftan o’ the Puddin-race! The Queen doesn’t know what to say, so she greets the next patient, who says, Swith! in some beggar’s haffet squattle; / There ye may creep, and sprawl, and sprattle. Disturbed, she moves quickly to the next patient, who rattles off even more extravagantly: Wee sleekit, cow’rin, tim’rous beastie, / O, what a panic’s in thy breastie! By this time, the Queen thinks she knows the nature of the illness. She turns to her guide. The mental ward? she asks. No, he replies. This is our Serious Burns Unit. I can relate. Throughout this pandemic time, I too have been an inpatient at the Serious Burns Unit.

Then, after dinner on May 3, 2020, I poured boiling water over tea bags into two Fiestaware mugs and started toward the living room to deliver them to my wife and son. Remembering that I had do to something first, I set the mugs back on the counter. But I didn’t let go of the mug in my right hand, and my finger caught in the ring handle, pulling the mug off the counter and tipping the just-boiled water onto the top of my socked foot.

Pain like I’ve never felt before. Agony beyond compare. I screamed. I pulled off my sock, some skin with it. I yelled for ice as family ran to me in the kitchen. My son quickly looked to his phone, and said: no ice, apply tepid water. I hobbled upstairs to the bathtub where I sat on the edge and washed away already shriveled, papery skin. I hoped the pain would ease. It did not. The burn extended across my foot, from just above my little toe to just above my big toe, a swath that narrowed to the top of the foot toward the tendon just above my ankle. Later, when I held my foot up, the burn was an inverted fiery triangle that my wife called the “Texas Tornado.” I certainly felt tornadic, sweaty, dizzy, and nauseated. I vomited. We drove to the emergency room. My heart rate and blood pressure were low, and I was still sweating. Intake nurses attached electrodes for a quick EKG, then finally led me to a bed. I was hooked to IV fluids. My foot was X-rayed.

Topeka has no burn specialists, but the emergency room doctor was thorough, capable, and kind, as was my nurse. IV painkillers joined the fluids; my heart rate returned to normal. My foot was salved and dressed, an appointment made for me at the University of Kansas Medical Center, an hour away, and I was sent home to sleep, aided by enough Oxycodone to get me through the night.

Early the next morning, my wife drove me to the KU Med Center through a gully-washing downpour. Covid protocols meant that she had not been with me in the emergency room, nor could she enter the hospital in Kansas City. I was on my own, wheeled by an attendant to the burn clinic, where a PA cleaned, evaluated, and dressed the wound. Mine was deemed a second-degree burn, which is also called a “partial thickness burn.” It affects both the epidermis, the first layer of skin, and the dermis, the lower layer of skin, causing pain, redness, swelling, and blistering. Second-degree burns can often be treated with creams and ointments. The PA taught me how to change the dressing, which I was to do once before returning for a follow-up appointment. This was a Monday morning, and I would be evaluated again on Friday. I was prescribed more Oxycodone, given a special boot for walking, a foam triangle to aid elevation, ointments, gauzes, and adhesive ribbons.

Describing pain is an art. Some want to know where you are on a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the worst. I was 11 or 12 for at least two days, with pain I had never thought I would experience, though I’ve broken ribs and ankles, separated a shoulder, torn biceps and my rotator cuff, endured post-surgery recovery, and had numerous wounds that required stitches. My advice: do not burn yourself; you do not need to add that particular pain—searing, jarring, throbbing, needling, and constant—to your repertoire.

Wednesday of that week, my sister, a PhD nurse and nursing professor, came to our house, fully masked, to help my wife and me change the dressing. We all thought the wound, though raw, red, and weeping, looked okay. By Friday, though, back at KU Med, my condition had worsened, with signs of infection—pus, swelling, red streaks—and continuous pain. This second-degree burn was trending toward the third degree. Doctors came to evaluate, and I was told I’d be staying in Kansas City for a skin graft. A negative Covid test meant I could be officially admitted to the burn unit. The surgeon dropped by to examine the foot; he would not have time in his schedule before Sunday morning, May 10—Mother’s Day—to perform the surgery.

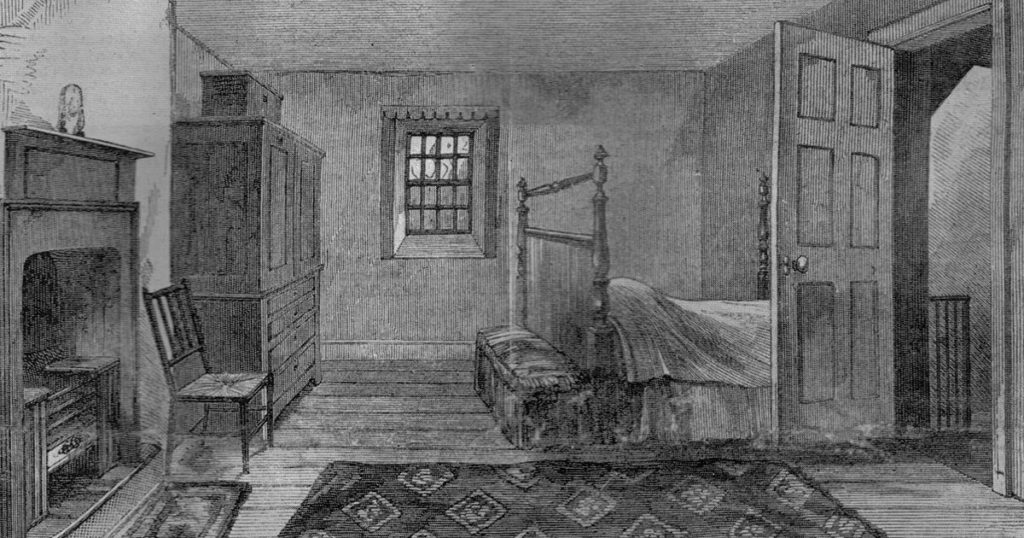

Though alone, I did not feel lonely. I had great attention from the nursing staff. I was in the middle of a long book, The Sympathizer, by Viet Thanh Ngyuen. I had my cell phone. And I had Robert Burns. Having spent more than a year in the Serious Burns Unit, I was used to spending hours alone with the poems in my head, letting each line bubble in my brain, from the four-line “To Miss Ainslie in Church,” to the long “Tam O’ Shanter.” I also had the memory of hearing the poems recited by my father so often at family dinners, from my high school years forward, that in this way, I had my family with me, too. That was comfort, generally, but also specifically, because I could use lines from Burns to help me think about my own burn, and the pain, and the double isolation of my situation. I’d quarantined in the comfort of home, but now my world was shrunken to a small bed in a small room in the burn unit.

I could feel sorry for myself with lines from Burns’s 1781 “A Prayer Under the Pressure of Violent Anguish”:

But if I must afflicted be,

To suit some wise design;

Then man my soul with firm resolves

To bear and not repine!

And console myself with lines from “Tam” like,

But pleasures are like poppies spread,

You seize the flow’r, its bloom is shed;

Or like the snow falls in the river,

A moment white—then melts forever;

Or like the borealis race

That flit ere you can point their place;

Or like the rainbow’s lovely form

Evanishing amid the storm.

Nae man can tether time or tide

The hour approaches, Tam maun ride.

I was Tom, who must ride into surgery. Preparing myself for the procedure, I remembered Burns’s last lines from “To A Mouse”: “And forward though I canna see, / I guess an’ fear.” Yes, fear. Going under the knife is always dangerous, more so the older we become. As Burns writes in “Scots Wha Hae,” “Welcome to your gory bed, / Or to Victorie!”

Post-surgery and eager for home, I could think of wife and family with all our shared experience, as in “John Anderson, My Jo”:

We clamb the hill thegither,

And monie a cantie day, John,

We’ve had wi’ ane another:

Now we maun totter down, John,

And hand in hand we’ll go …

And my favorite of Burns’ love poems, “O, Wert Thou In The Cauld Blast,” gave me solace:

Or were I in the wildest waste,

Sae black and bare, sae blac and bare,

The desert were a Paradise,

If thou wert there, if thou wert there.

Though my family could not visit me pre- or post-op, I had excellent care. The surgeon and staff described the process thoroughly. I would be my own donor. They would harvest the top layer of skin from my upper left thigh, a patch of about four inches, and attach it to my foot. Both sites—now two wounds instead of one!—would be well sealed with ointment and specially treated coverings to aid in healing. I would spend Sunday in recovery. I would have plenty of pain killers, but would be expected to be able to urinate, to walk, and to be eating well before I would be released.

That Sunday, I was fuzzy, too exhausted and traumatized to do much more than talk briefly on the phone, read a bit, and recite cheerful Burns, like the first stanza of “The Ploughman’s Life”:

As I was a-wandering ae morning in spring,

I heard a young ploughman sae sweetly to sing;

And as he was singin’, thir words he did say, —

There’s nae life like the ploughman’s in the month o’ sweet May.

Or the contented Burns of “Green Grow the Rashes”:

But gie me a cannie hour at e’en,

My arms about my dearie, O;

An’ war’ly cares, an’ war’ly men,

May a’ gae tapsalteerie, O!

Monday brought the surgeon around to examine the wound. His optimism and good wishes for steady healing were a comfort, too. The physical therapist brought in a platform and taught me how to approach climbing stairs, since we have plenty in our home. She gave me a useful mantra: “Up with the good, down with the bad.” I was imitating “John Barleycorn,” who “got up again, / And sore surpris’d them all.” On Tuesday, I returned home. Again, I had plenty of prescription help with pain, Gabapentin for nerve pain added to the Oxycodone, and this time a more elaborate boot, and a plastic male urinal cup for nighttime use. We borrowed a walker from a friend who had recently had knee surgery. I moved about like Willie’s wife in “Sic’ A Wife As Willie Had”:

Ae limpin’ leg a hand-breed shorter;

… twisted right, … twisted left,

To balance fair in ilka quarter.

By the time I returned to KU Med the following Friday for my first checkup, I was walking with a cane, and my pain was lessening. The worst part of the visit was the sight of my foot. I’m amazed by the technology, the instruments, the surgical skill, and the expertise that allow someone to remove a layer of skin from one part of the body and attach it to another. But the wound looked nothing like art: the grafted skin attached to the top of my foot might have been a piece of burlap stapled to a wall. Primitive and ugly. Yet the foot and the donor site were healing as expected. About a week later, I had another appointment, again a dressing change, with such good results that from then on, all my appointments could be conducted via Zoom.

During this recovery time, I camped out in a leather reclining chair. I was waited on, cooked for, helped up the stairs at night. For someone who takes pride in independence, and in doing for others, I learned the pleasure of being cared for. Others brought me my morning green tea. I finally began that long essay about the poetry of Burns and its influence on my father and my grandmother. Elizabeth Carson was born in Massachusetts in 1890, just a few years after her parents came to the United States from Scotland. Her birth was less than a hundred years after the death of Burns in 1796. She could recite his poetry, and, accompanying herself on the piano, she sang the lyrics Burns wrote to the music he collected for the Scots Musical Museum. Such lines as these, from “Ae Fond Kiss,” were in her memory: “But to see her was to love her; / Love but her and love forever.” My father, once he began reconnecting with his Scottishness, found he had inherited a fine brogue. He loved the tongue-twisting dialect in a poem like “Sic A Wife As Willie Had”:

Auld baudrons by the ingle sits,

An’ wi’ her loof her face a-washin;

But Willie’s wife is nae sae trig,

She dights her grunzie wi’ a hushion.

Now, a year and a half later, my scars have faded. My upper thigh, where the donor skin was removed, has only the faintest sign that it was once a healing reddish sacrificial patch. The Texas tornado on my foot is now a cirrus cloud, with only wispy remnants of scar tissue on the surface. When first burned, and then recuperating, I could and did regale family and friends with the story of what happened, could show the scars to those not squeamish. Now, the past receding, I might mention it, though rarely, given the context of the conversation. I am still scarred by that burn, physically not as much, but certainly emotionally. The experience surfaces each time I pour boiling water into a Fiesta mug and begin to carry it from the kitchen—a sort of post-tea stress disorder.

Perhaps, like the burn, it is only appropriate to speak of Burns’s poetry when occasioned by conversation. Or among intimates, most particularly my family, which, because I’m carrying on a tradition begun by my grandmother and continued by my father, will ask me to recite Burns, and tolerate me when I hold forth unbidden. Another of our family traditions in recent years has been the celebration of Burns Night, on a day close to the poet’s birthday, January 25. We gather with others who share family and cultural ties to Scotland. Then, we all read Burns, recite Burns, sing Burns. The pandemic interrupted this tradition, and this year, our gathering was considerably smaller. Besides the obligatory “Address to a Haggis,” we included a recitation of “Auld Lang Syne,” meaning “old long since,” so aptly describing the pleasure of meeting again, of taking that “right gude-willie waught,” that “cup o’ kindness,” sharing the best of what marks us, and forgetting the worst of what scars us.

During that glorious evening, our hearts o’erflowed with joy. We were, each of us, admitted into the Serious Burns Unit.