Shakespeare’s Sisters: How Women Wrote the Renaissance by Ramie Targoff; Knopf, 336 pp., $33

“Shakespeare’s Sister” is an oblique reference to Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay “A Room of One’s Own,” in which the British writer imagines that the Bard had an equally talented sister named Judith. With little opportunity and few protections, Judith meets a tragic end, despite her innate brilliance. Woolf seeks to prove a point: that for women to write, they need the space and time to put pen to paper. Today, several writers’ retreats and residencies for women—such as Hedgebrook, Storyknife, and the Torch Literary Arts Retreat—have been established in recognition that some women benefit from time away from quotidian responsibilities to conceive and nurture new writing. But what happened to women who dreamed of writing in Renaissance England? They were “but to be quoted in the margin,” writes Ramie Targoff. At last, in Shakespeare’s Sisters, they occupy the center of the page.

Targoff, the Jehuda Reinharz Professor of the Humanities at Brandeis University, follows four women who wrote during Shakespeare’s time: Elizabeth Cary, Anne Clifford, Aemilia Lanyer, and Mary Sidney. Left out are other deserving writers, such as Aphra Behn and Margaret Cavendish, but the book’s narrow focus makes for a more intimate series of portraits, set against the rich background of Renaissance England, William Shakespeare, and Queen Elizabeth I. Targoff begins by sketching the cultural and gender norms of the time, how women were to obey and serve—first their fathers, then their husbands. Under the doctrine known as coverture, men became the legal guardians of their wives. Renaissance women were supposed to be quiet in public. If judged disruptive, they risked being called “scolds,” Targoff writes, and “paraded through the streets wearing a heavy iron muzzle known as a ‘scold’s bridle.’” Most institutions of learning, including universities, excluded women, and “whether a girl received any kind of education in Renaissance England depended entirely on her family circumstances.”

Shakespeare’s Sisters’s opening chapter introduces us to Queen Elizabeth I, who served as a role model for other women writers of the era. “From early in her childhood,” Targoff writes, “Elizabeth had been encouraged not only to study a wide range of languages but also to write things of her own.” The story of her poem written at Woodstock Palace—which she carved into a window with a diamond while being held prisoner there during the reign of her half-sister, Mary I—is a gem of an anecdote: “Much suspected by me, / Nothing proved can be, / Quoth Elizabeth prisoner.”

Targoff moves chronologically through her four subjects’ stories, alternating among them and studding her narrative with well-researched details. Maps of each woman’s family lineage open the book, but Shakespeare’s Sisters doesn’t live exclusively in the dust of history; there are moments in which Targoff knits the past to the present. For example, her discussion of the bubonic plague, which racked England centuries ago, may remind readers of their own experiences during the Covid-19 pandemic. As the story goes, Margaret Clifford, Countess of Cumberland and mother of Anne, restricted her daughter from attending court during an outbreak.

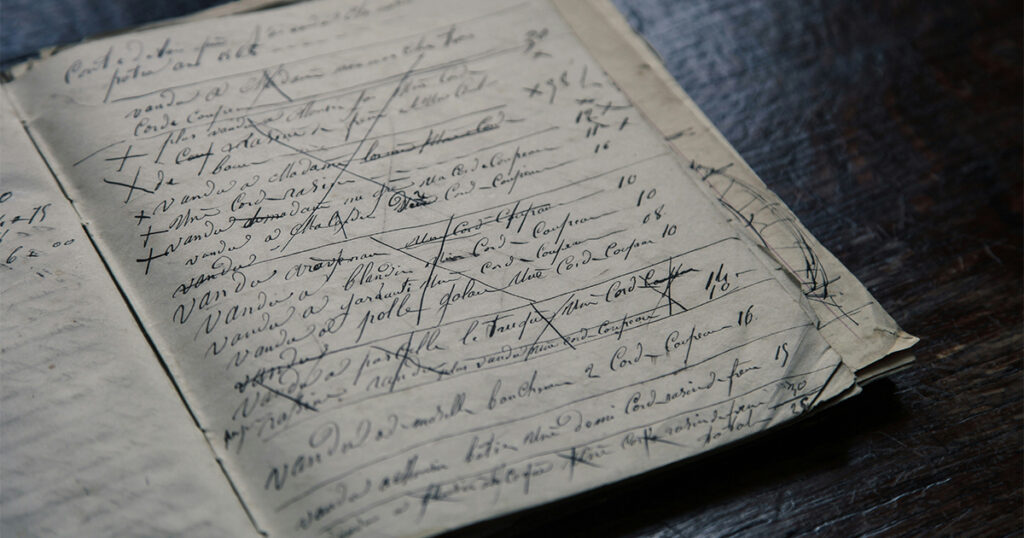

The women’s writing ranged from translations to poetry to history to drama, and more. Three of the four were either aristocrats or members of the wealthy bourgeoisie, Targoff writes. Therefore, their lives were recorded in more detail than those of most other women of the day. Aristocratic women married men in public office, had families at court, and employed secretaries and stewards to keep track of personal writings. Aemilia Lanyer, born of “the middling gentry,” became the first Englishwoman in the 17th century to publish a book of original poetry, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum. Of her life we can resurrect only certain moments, using knowledge of the times to fill in the blanks. Working families such as Lanyer’s—court musicians with ambition—would hope “high-ranking families … might give their daughters opportunities they couldn’t themselves provide,” Targoff writes. In this manner, Lanyer’s life was transformed when her mother sent her to be “brought up with the countess of Kent”—Renaissance England’s version of upward mobility.

Reading about Mary Sidney, the Countess of Pembroke, we learn of her zeal for translation. With a class stigma on publishing and the idea that it was considered vulgar for English aristocrats to share their writing with the larger public, Sidney could not on a whim decide to walk into the literary world. It was the death of her brother Sir Philip Sidney that opened a door. The siblings’ close relationship positioned her to complete his unfinished translation of the Book of Psalms. Mary ultimately translated more psalms than her brother had and became the first writer to render the entire Book of Psalms in English poetry. “In the 107 psalms Mary translated on her own,” Targoff writes, “there are 128 different combinations of stanza and meter.” Her work was a deft display of the poet’s craft.

Pulsing with juicy biographical details, Shakespeare’s Sisters has its page-turning moments, with more twists than any contemporary television show. We read, for example, of Anne Clifford’s 38-year legal battle over her inheritance and of Elizabeth Cary’s early education in examining a witch. (Cary’s father, Lawrence Tanfield, a lawyer and MP, allowed his daughter in the room as he conducted the formal interrogation of the accused witch. It was Elizabeth’s suggested line of questioning that ultimately freed the woman from a gruesome fate.) We learn of Mary Sidney’s sojourns in the Belgian town of Spa to improve her failing health and Aemilia Lanyer’s visits with Simon Forman, an astrologer and dubious medical healer who made house calls. Forman, it was said, “could read an astrological chart, perform minor surgery, and call spirits from the dead all in a single session.” In a way that pre-dates the Bechdel test, husbands and children enter and exit the story without ever stealing the spotlight from the women.

One of Targoff’s early statements lingers long after it has been introduced: “However much we thought we knew about the Renaissance, it was only half the story.” How many more of Shakespeare’s Sisters might there have been? In so much of Renaissance England, with one royal exception, women were ancillary characters in their own stories. In Shakespeare’s Sisters, Targoff enthusiastically corrects history’s misogyny and casts her subjects in the starring roles that they always deserved.