It Happened One Day in June

Why Ulysses is as vital as ever— compelling, complex, and direct

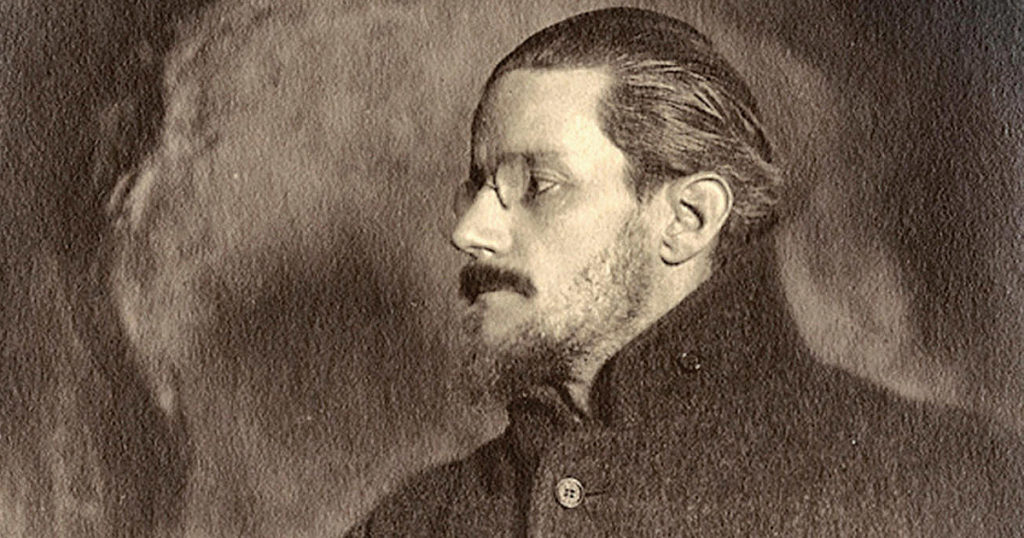

Like many great works of art, James Joyce’s Ulysses has an existence beyond the printed page, an artistic half-life that has endured now for 100 years. It is a novel to learn from and obsess about, and you can spend a lifetime immersed in its pages. Nevertheless, many uninitiated readers view Joyce’s epic with paralyzing fear, something the author didn’t exactly allay with this admission in the mid-1920s: “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant, and that’s the only way of insuring one’s immortality.” The stance is flippant, though in many ways, Joyce intended for the novel to be intimidating. Ulysses is not fast food. It discomfits conventional wisdom, challenges ossified beliefs, attacks commonplaces, jogs perceptual patterns. Many of the emotions and actions plumbed in the novel are unsettling. But if the fictional world of Joyce’s making is contradictory and multilayered, so too is human existence, with its jumble of joys and frustrations.

Joyce was an incomparable wordsmith—after Shakespeare, our most inventive linguistic virtuoso. He was also a venturesome explorer, the premiere articulator of how the mind works, how random thoughts can provoke evocative images or crippling memories, how consciousness constantly breaks in on its own narratives, causing jumps, retreats, and retrackings, revealing the mind’s wondrous or onerous penchant for offering up a consonant impulse or conflicting desire. The thoughts and feelings of the three principal characters—Leopold Bloom, Molly Bloom, and Stephen Dedalus—often do battle with the slippery, even uncontrollable nature of mental recall. They, like so many of the characters inhabiting Dublin on a single day (June 16, 1904), are memorable individuals, supremely believable. Which is why, in spite of the hurdles the author self-consciously sets up for his audience—the allusions, the wordplay, the Homeric resonances, the interiority of the monologues—the book is as compelling today as it was a century ago. There’s a surprising clarity about Ulysses, despite its many complexities. Joyce can at times be stunningly direct and, yes, exquisitely economical.

The novel is primarily about the failure of the Blooms’ marriage, with both Leopold and Molly finally recognizing at least partial responsibility for the impasse. Molly, an ironic stand-in for Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey, stays at home like her classical counterpart, having been deprived of intercourse with her husband for 10 years, five months, and 18 days. Why such epic abstinence? Because, after the death of their 11-day-old son, Rudy, Leopold has been unable or unwilling to make what is generally considered conventional love with his wife.

Beyond an accounting of this marriage on the rocks, Joyce’s bounteous fiction also fathoms the heart and mind of the 22-year-old Stephen Dedalus, the tormented spendthrift whose extravagant literary-aesthetic-philosophical consciousness is both a treat and a hurdle for readers. Stephen is an emotional disaster, an arrogant literary pretender sorely ignorant of women and thus far in his life incapable of love. He’s also hilarious, a cool appraiser of others’ limitations. An artist manqué, he is also preternaturally alert, a cogent thinker who entertains himself by contemplating classical theories of knowledge, perception, and aesthetics. Above all, he delights in language. Joyce holds out the teasing possibility that this balked, grumpy misfit might someday become a major writer—emphasis on the might.

Young Stephen is also an alcoholic, and it is this affliction that could well be the ruin of him. While teaching his morning class at Mr. Deasey’s school, he desperately desires a drink, a craving he will satisfy at lunch, when he treats himself to an alcoholic beverage or two. On and off, his boozing will continue throughout the day and night. He’s not the only one. Almost every male who appears in the novel is a heavy drinker or a drunk, the teetotaler Leopold Bloom being the principal exception. Stephen’s father, Simon Dedalus, wastes his limited resources on alcohol. In Barney Kiernan’s pub, the belligerent Citizen and his drinking companions verbally swagger and argue and nearly come to blows while rounds of drinks are imbibed. No wonder Bloom muses, as he navigates his way through an alcohol-soaked Dublin: “Good puzzle would be cross Dublin without passing a pub.”

Few novels are as wedded to its setting as Ulysses is to Dublin, which in the early 1900s had a population of a little more than 400,000. Ulysses is an attempt to write a modern epic that captures the simultaneity, confusion, and layered nature of what it’s like to live in a small yet highly complex early-20th-century urban setting. To a writer of Joyce’s sensibility, cities are happy hunting grounds for explorations in time and space, offering intersections, interstices, inexhaustible angles, constantly changing perspectives: all this along with a ceaseless soundtrack of clamor, music, and chatter. Joyce last saw Dublin in 1912, having purposefully exiled himself from his hometown some years earlier, aware that neither his life nor his work could flourish in the repressed, impoverished, guilt-ridden world dominated by the Roman Catholic Church and English colonialism. Yet mentally he never absented himself from the city of his birth. His major works—Dubliners (1914), A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916), Ulysses (1922), and Finnegans Wake (1939)—are all set in that “dear dirty” locale.

Dublin’s relatively compact city center maximizes the Blooms’ personal drama. Leopold Bloom is constantly on the move, throughout the day and half the night, ever alert to his surroundings, yet the claustrophobia induced by the city’s centripetal forces causes him to be agonizingly aware of the presence of one Blazes Boylan—the man who will become Molly’s lover that afternoon. Throughout the day depicted by the epic, Bloom is plagued by a number of near-collisions with the contender for his wife’s amorous favors. Blazes Boylan seems to be everywhere. In a harrowing scene outside the National Library, Bloom races to avoid being spotted by his rival, and that sprint leads to the out-of-breath, exquisitely wrenching utterance, “My heart!” Which happens to be breaking—as he counts down the hours to his wife’s scheduled four p.m. assignation with the “worst man in Dublin.”

Partly due to its sexual content, Joyce’s epic was prosecuted for immorality— a cruel, crude irony. For Ulysses is a moral tale, deeply concerned with its characters’ ethical responsibilities to each other, scrupulously weighing the principals’ helpful and hurtful actions, their generous impulses and cowardly evasions. Leopold’s complicity in the failure of his marriage, Molly’s decision to take a lover, Stephen’s bad-faith excuses for dodging his family’s desperate financial plight—these civil wars raging within each of the characters (and, by implication, within all of us) are presented with minimal didacticism or sentimentality.

And yes, there’s a sense of defiant glee in the author’s decision to graphically present sexual pleasure in a work published in 1922. But the novel is not an unthinking sensualist’s tract about the joys and the disappointments of eros. No fiction I know incorporates such an incisive portrait of the shifting relativities of an intimate relationship. Ulysses is acutely aware of the complex psychology of sex and obsessions, of hang-ups and disappointments, of the lures of sadism and masochism, of the incendiary potential of the erotic.

Ulysses aficionados have the curious habit of treating its characters as though they are alive. We poor sods know better, but the identifications are so strong, the emotional issues so much a part of ourselves, the unsolvable dilemmas so engaging, that Leopold and Molly and Stephen occupy a unique niche in the fanatic’s universe. Indeed, the novel’s enigmas create ongoing debates about the future. What will become of Molly and Blazes Boylan? Will Leopold, like his epic progenitor Odysseus, set his own house in order? Will Molly and Leopold revive their moribund sexual relationship and delight each other again? And again? Will Stephen Dedalus escape his crash-and-burn trajectory and become the artist he aspires to be, capable emotionally, intellectually, and artistically of writing an epic like Ulysses ? These questions can easily become lifelong obsessions. I would invite every reader to explore the answers, to revel in Joyce’s language, which twists and turns on the page, the metaphors expanding the landscape of the reader’s mind, a human cosmography unlike anything else in literature. James Joyce’s epic demands a good deal of application, but, dear Reader, it’s more than worth the effort.