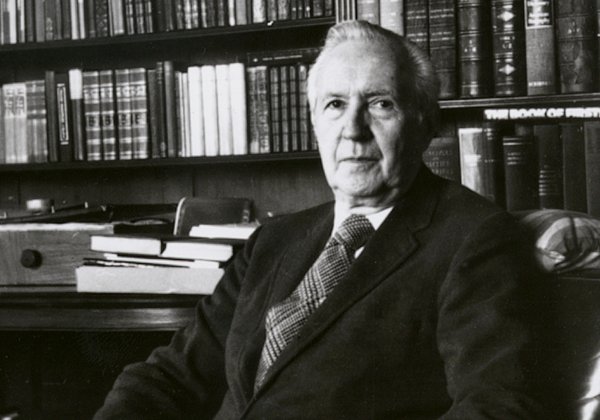

Jacques Barzun—and Others

The eminent scholar was among the last representatives of a grand literary tradition

Last week, the distinguished cultural historian, teacher, and man of letters Jacques Barzun died at the age of 104. For a while there, it seemed that Barzun—rhymes approximately with “parson”—might go on forever, adding to our knowledge of the past, assailing the decline of standards, both exemplifying and fighting for cultured, civilized values. Certainly up through his 90s, he had remained active as a scholar and writer, even producing a surprise best seller From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life, in 2000, when he was 92.

This past year Michael Murray brought out Jacques Barzun: Portrait of a Mind, tracking his subject’s astonishing life from a French boyhood in which Barzun played marbles with the poet Guillaume Apollinaire through a brilliant career at Columbia University, first as an undergraduate, then as a teacher, and finally as the university’s provost. Murray relates a particularly delightful story about young Professor Barzun. In one of his first history classes, Barzun recalled, there “was a beautifully dressed man of about forty, with very black hair and a signet ring with a diamond and a tie pin; he was done up to the nines. At the end of the first semester, he came to me and said: ‘I am a Turk, and I want to express my gratitude because in your dealing with the Turkish question you have been perfectly fair. This means so much. I want to tell you that if ever at any time someone stands in your way or has done you harm, here is my card, just call me, and he will be taken care of.’”

Barzun then added, “I have strewn the byways with my victims.”

Barzun’s best-known books include Berlioz and the Romantic Century, Teacher in America, A Stroll with William James, and Simple and Direct, a guide to writing. But I’ve always thought that A Catalogue of Crime, written with his lifelong friend Wendell Hertig Taylor, could be his most lasting masterpiece. I keep it by my bedside, along with a handful of similarly wide-ranging and often idiosyncratic reference books, such as E. F. Bleiler’s Guide to Supernatural Fiction and Martin Seymour-Smith’s New Guide to Modern World Literature. All these books are dog-eared and marked up, with loosened bindings; booksellers sometimes facetiously describe their condition as “much loved.” My own copy of A Catalogue of Crime certainly fits that description, even though I generally disagree with many of its harsh judgments on modern crime fiction. Barzun and Taylor definitely prefer classic whodunits, especially those written with wit, panache, and, above all, cleverness. The Catalogue lists more than 5,000 novel-length mysteries, collections of detective stories, true-crime books, and assorted volumes celebrating the delights of detection. Every entry is annotated, and a succinct critical judgment given. For instance, John Dickson Carr’s historical reconstruction The Murder of Sir Edmund Godfrey is summed up as “a classic in the best sense—i.e., rereadable indefinitely.” The brief account of Murder Plain and Fanciful, edited by James Sandoe, opens: “This virtually perfect anthology seems never to have been reprinted, which is a disgrace as well as a deprivation to the reading public.” Dorothy L. Sayers’ Strong Poison reads in as follows in its entirety:

“JB puts this highest among the masterpieces. It has the strongest possible element of suspense—curiosity and the feeling one shares with Wimsey for Harriet Vane. The clues, the enigma, the free-love question, and the order of telling could not be improved upon. As for the somber opening, with the judge’s comments on how to make an omelet, it is sheer genius.”

I like to think of Barzun spending the first decade of the 21st century, reading and rereading his favorite authors, in particular, Conan Doyle, Rex Stout, and Agatha Christie. He once wrote that Archie Goodwin, the legman for Stout’s fat detective Nero Wolfe, was a modern avatar of Huck Finn and one of the most memorable characters in American literature.

As a teacher, Barzun taught any number of distinguished writers, from science fiction giant Robert Silverberg to the cultural essayist Arthur Krystal and the award-winning musicologist Jack Sullivan. He was also, of course, a great supporter of, and contributor to, The American Scholar. Alas, I never knew him, except through his books. But I have been lucky enough to meet two other great centenarians of scholarship: M. H. Abrams and Daniel Aaron. Abrams taught at Cornell, where—in another life—I earned a Ph.D. in comparative literature. He retired a year after I got there, so I only knew him very casually and wasn’t able to take any of his classes. His masterpiece, The Mirror and the Lamp, tracks the shift from classicism to romanticism in English poetry. From all reports he remains vigorous, this fall even bringing out a new collection of occasional pieces, The Fourth Dimension of a Poem and Other Essays. Daniel Aaron, of Harvard, is one of our most revered Americanists, author of the classic study Writers on the Left, editor of Edmund Wilson’s letters, co-founder of the Library of America, and famous for riding his bicycle all around Cambridge well into his 90s.

When I first began to work as an editor at The Washington Post Book World back in the late 1970s, it was my habit to call up elderly writers and scholars and ask them to review for me. My secret reason for this was simply to connect, however briefly, through letter, telephone call, or handshake, with these eminent men and women, but also with the great writers who had been their friends and associates. Favorite authors like Scott Fitzgerald, Edmund Wilson, W. H. Auden, and Evelyn Waugh were already dead, but I could reach out to Malcolm Cowley, Peter Quennell, Eleanor Clark, Rex Warner, Stephen Spender, Sir Harold Acton, Sir John Pope-Hennessy, Douglas Bush, and many others. Once a retired Boston University professor reviewed two books about T. E. Lawrence, with whom he had done brass rubbings while they were both undergraduates at Oxford. Warren Ault wrote the review at age 102.

These days I occasionally correspond with the great Dostoevsky biographer and critic, and former Princeton and Stanford professor, Joseph Frank, who is in his mid-90s. Just this year, he too brought out a new book, Responses to Modernity: Essays in the Politics of Culture. It includes essays on, among others, Paul Valéry, André Malraux, Ernst Juenger, T. S. Eliot, and two of his former colleagues, the critic R. P. Blackmur (of Princeton) and the pioneering scholar of the novel Ian Watt (of Stanford).

Figures like Jacques Barzun—and Abrams, Aaron, and Frank—seem to me the last representatives of a traditional literary scholarship that is now out of fashion. To this group, one might include a few octogenarians, such as Abrams’s former student Harold Bloom and the comparatist and Bible translator Robert Alter. No doubt there are others I am overlooking. But these academic eminences have all worked hard to become truly learned, and their scholarship is vitalized by a deep knowledge of, and serious engagement with, the great works of the past. Until last week, Jacques Barzun was the oldest, and one of the best, of these living cultural treasures.

Read Jacques Barzun’s “The Cradle of Modernism,” published in The American Scholar in 1990.