Jane Austen’s Ivory Cage

What lies beneath the surface of the grand estates and courtly balls

When I was working on my doctorate at Oxford, I lived in a large Victorian house with about 10 other students. My room was on the ground floor at the back; in the room above me lived a Canadian woman named Lenore—after the “rare and radiant maiden” in Poe’s “The Raven,” she once told me, though her mail was addressed to Margaret. She wore square, black-framed glasses, lots of lipstick, and old-fashioned lace-up boots. Though she was straight, she had what was generally considered to be a lesbian haircut (shorn at the sides and thick on top), and she was also impressively tech-savvy. One evening, she announced that she was going to the computer room to “log on,” a phrase literature students didn’t often utter in 1992.

One afternoon, I answered the house phone and heard Lenore’s panicked voice on the other end of the line. She was at a conference, and she’d forgotten her paper; would I mind faxing it to her? When I got to the grad student lounge and started feeding the pages into the creaky fax machine, I started to read them out of curiosity. When I found she was a Jane Austen scholar, the fact that she was both technically skilled and supremely disorganized somehow seemed to fit. Her thesis was about gout in Austen’s novels. The malady, I learned, used to be known as the “disease of kings” because people thought it was caused by a rich diet. Most of the time it begins with intense pain in the big toe; then the feet start to ache and burn. Until then, I’d always thought of gout as something old people grumbled about in the past, like dropsy or goiter, but as Lenore explained in her paper, it’s still around, and it’s one of the most excruciatingly painful diseases imaginable. Gout makes your feet so sensitive that even the touch of a bedsheet is agony (18th-century artists drew Gout as a red demon that bit your toes, or stabbed them with a burning poker). Austen herself didn’t have gout, and her only gouty character is an incidental Mr. Johnson in the unpublished epistolary novel Lady Susan. But according to Lenore, it was always there in the background, like the Napoleonic Wars. By the time the last page of the fax had gone through, I’d come to the conclusion that Lenore was bats.

Personally, I’d been swept up by French poststructuralism and other fashionable aspects of critical theory. My impulse was to look forward to new currents in philosophy and thought, rather then looking backward, or limiting my ideas—as I saw it then—to a particular author, period, or theme. These days, I think Lenore probably made the smarter choice. If I had to do my doctorate again, I’d choose something just as specific. The best way to understand anything in general, I’ve learned, is by going as deeply as you can into the particular. This was something Jane Austen knew well; she famously likened her work to painting with a “fine brush” on “a little bit—two inches—of ivory.” I know the pleasure, now, of looking at that little piece of ivory for long enough to become absorbed, as Austen did, in the details of a miniature world.

A lot of people say that reading Austen puts them in a stupor. It puts me in a stupor too, but it’s a stupor I love. No matter how many times or how recently I’ve read her novels, as soon as I pick one up again, I’m immediately and reliably drawn back in. I spent a recent summer rereading Austen for a class I was planning to teach in the fall. In late August, shortly before the class began, I uploaded audio versions of the novels to the course website. To check that the files worked properly, I started listening to Sense and Sensibility—and it felt as though an Austen devil was biting my big toe. The next thing I knew, I had a full-blown case of Austen fever and didn’t recover until I’d listened to all six novels again, end-to-end.

The students in my class, 90 percent of whom were women, loved all the Austen-themed groups and activities they found on the Internet. They turned up every week with their “I ♥ Mr. Darcy” tote bags and “Team Bingley” laptop skins, and told me about their favorite Austen-themed graphic novels, fiction spinoffs, and social networking games. They sent me links to Austen blogs, Austen tours, and an Austen app that delivers a witty quote to your iPhone every day. One girl gave me a tin of Austen Band-Aids.

I’d have found such things just as delightful when I was their age, but now it feels too late. I was 16 or 17 when I discovered Austen, and my feelings about her have changed over the last 30 years. It’s difficult, today, for me to see the point of anything that’s extraneous to the work itself. When I was 18, my favorite of the six novels was the charming Gothic fantasy Northanger Abbey. Now it’s Mansfield Park—the “problem novel” that even die-hard Janeites find difficult to enjoy.

Critics such as Lionel Trilling have argued that the book’s problems all stem from the passive reticence of its heroine, Fanny Price. Timid Fanny isn’t everyone’s idea of a strong female protagonist, for sure, but neither is she the prim, irritating little goody two-shoes that Trilling makes her out to be. Still, when the time came for me to introduce my students to Mansfield Park, I wasn’t sure—knowing how much they’d loved feisty Elizabeth Bennet and bold Emma Woodhouse—what they’d make of mousy little Fanny, who spends the first half of the book crying in her bedroom, too scared to light the fire or ask a servant to light one for her.

My students, as it turned out, both loved and pitied her. “I will be honest: I feel immensely sorry for dear Fanny,” wrote one young woman on the class blog. “I found that I was able to sympathize with Fanny very easily,” wrote another. “She has a beautiful character in my opinion.” Another wrote: “I can understand her crying a lot, and being timid. Though I have never been in a situation like hers, I would probably be the same way.” One wrote, “I feel like Fanny is relatable to a lot of people in a way that the other women of Austen’s novels might not have been.” The only real problem they had with Mansfield Park was when strait-laced Fanny, who thinks it’s sinful to put on a play in which one of the characters has an illegitimate child, marries her cousin. This, to my students, was a far worse transgression than having a child out of wedlock, especially since Fanny and Edmund have been raised in the same home. “Even though I know that it is accepted in their time, I still think it’s really weird and awkward that Fanny has a crush on Edmund,” wrote one. “It leaves a bitter taste in my mouth.” Another was more explicit: “Fanny should have married Henry. I know Jane Austen was going for this big romantic idea of true love or whatever but … Edmund was virtually her brother. No. Just no.”

Otherwise, the novel was well received. Most of the students said they identified with Fanny because they were introverts themselves and, like her, uncomfortable with self-exposure. I, too, identified with Fanny when I first read Mansfield Park, and for similar reasons. Now, however, I wonder whether the kind of pleasure we get from reading about girls like her—quiet girls who blush easily and dislike attention—might not have something a little spurious about it, something even masochistic. Austen makes it clear that humble Fanny, who sees herself as so undeserving, is far more interesting and intelligent than her privileged cousins Maria and Julia Bertram, whose constant desire for attention seems shallow and immoral. Fanny’s shyness makes her less prone to seeking out other people. Plus, she’s learned from watching her cousins that attention leads to trouble. Much better, thinks Fanny, to read books or work on her embroidery than make smart conversation or try out a new style of hat. Nobody in the story knows it (least of all Fanny), but she is a gem. But everyone reading the story knows it, and this being Austen—and not, say, Edith Wharton—we can hotly anticipate the comeuppance of everyone who’s overlooked or mistreated her, especially her busybody aunt and stuck-up cousins. Identifying with Fanny lets us enjoy a kind of sham self-abasement. But unlike her, we know it’s only temporary: we know there’s a big payoff coming.

This isn’t to say that I find the novels any less interesting or less addictive than before, just that I no longer find them romantic. As a cynical, clear-eyed adult, I see them not as nostalgic fantasies, but as finely wrought vignettes of unacknowledged suffering. The world of Jane Austen’s heroines—that “two inches of ivory”—is so small that everything matters almost too much, which is precisely what the world can feel like to an 18-year-old girl. When I was a teenager, my world was circumscribed to home and school. I was awkward and self-conscious, spent hours worrying about what to wear, and ruminated anxiously about the meaning of every social exchange, especially if it was with a boy. The tiniest breach in teenage etiquette could have all kinds of terrible repercussions, but the pain it caused couldn’t be expressed. Responses had to be regulated at all times. At 18, most girls live in a world of secret anguish. This is why young women such as my students can identify with Austen’s heroines—because they live, for the most part, in a similarly limited world.

If you’d asked me at that age why I loved Austen, I’d have talked about her novels’ sense of yearning, the romance, the men who see through showy appearances and fall hopelessly in love with the shy, sensible girl in the background, the one with the intelligent eyes. This, too, is what my students said. For the most part, they enjoyed Mansfield Park for the same reasons they enjoyed the other Austen novels we’d read—because they take you back to a time of refinement and elegance. My students loved talking about the grand country houses, the balls with half-hour-long dances, the old-fashioned courtship rituals, the families, the dresses, the weddings. I tried to tell them Jane Austen was all about pain, but, unsurprisingly, they refused to listen. “I myself prefer a novel that gives me an escape from the sometimes crude realities of this world,” wrote one girl. Another claimed: “Reading Jane Austen’s work simply makes me happy.”

In my own case, instead of thinking about the excitement of young ladies going to Bath or London for the season, I think of what it must be like for them the rest of the year—throughout those bleak, empty days with nothing to look forward to except a walk to the post office in the rain. These poor women spend pretty much every day at home until, if they’re very lucky (and pretty), they marry and move into somebody else’s house, and the whole thing starts again. They may have one or two female friends they can visit, and perhaps a horse to ride, but most of their days are spent waiting for something to happen. The long days are spent reading aloud, sewing, writing letters, or playing the piano. On the outside, in Austen’s novels, very little happens; on the inside, a great deal happens, but it’s rarely pleasant. People are constantly judging one another according to invisible, almost inseparable distinctions that are as thin and fragile as a porcelain teacup.

And then there’s the English weather. It’s a long time since I lived in that Victorian house in Oxford, but every time I go back to visit, even in summer, I’m reminded of that horrible, bone-chilling British cold. During the winter of 1963, it was so cold that the English Channel froze over. Sure, it can be frigid in the United States, but enough to freeze the sea? Plus, over here it’s cold in the winter, when you would expect, but only outside. Not so in England. I feel it everywhere, all the time, not just in older buildings, though drafty, rattling windows and a lack of insulation certainly make it worse. Almost every structure in Britain has central heating now, though when I ask if it can be turned up, the usual response is, “Why don’t you put on another sweater?” So maybe the feeling is psychological, but whenever I’m there, I sense that whatever’s standing between me and the elements is very, very thin—plunging me immediately into a depression. I’m sure it must have been the same in the 18th century, if not much worse. Forget about Prozac—they didn’t even have electricity.

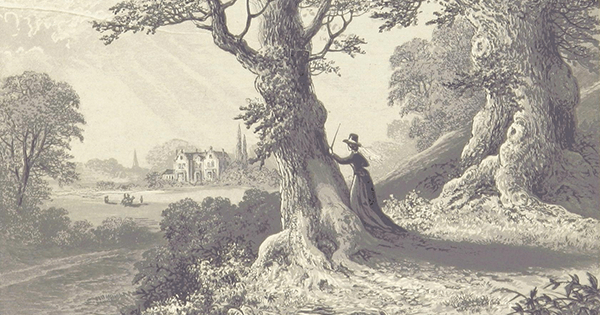

I now see Austen as a very dark writer and Mansfield Park as her darkest work, a book full of sexual repression and unconscious conflict, with no forgiveness or redemption for anyone who dares struggle against the social code. The world of taffeta and lace exists only on the surface; underneath it, these well-bred young women are trapped like rats. This fact is made most vivid in the scene where Fanny joins a party of friends and family on their visit to Sotherton Court, the home of her cousin Maria Bertram’s wealthy but deathly boring fiancé, James Rushworth, whose extensive grounds include a bowling green, lawns bounded by high walls, pheasants, a wilderness, a terrace walk, iron palisades, and a small wood.

The layout of the scene and its psychology are closely interlinked. As usual, everyone in the party forgets about frail Fanny, who, exhausted by the summer heat (she should have been grateful it was above zero and not raining), spends most of the afternoon on a garden bench beside a ha-ha—a type of sunken ditch used to separate cultivated garden areas from open parkland. A small bridge crosses the ha-ha, on the far side of which is a locked gate. From her seat on the bench, Fanny waits and watches everyone’s behavior with mounting agitation. At one point, she overhears Maria flirtatiously asking their neighbor, the handsome Henry Crawford, whether he thinks she’s as lively as her sister.

Henry’s reply is ambiguous. “You have a very smiling scene before you,” he observes.

“Do you mean literally or figuratively?” says Maria. “Literally, I conclude. Yes, certainly, the sun shines, and the park looks very cheerful. But unluckily that iron gate, that ha-ha, give me a feeling of restraint and hardship. ‘I cannot get out,’ as the starling said.”

As Maria speaks, she crosses the short bridge and approaches the locked gate. Rushworth has been sent to find the key, but unwilling to wait, Maria begins to climb the fence. Fanny, alarmed by her cousin’s inappropriate behavior, grows frantic. “You will hurt yourself, Miss Bertram,” Fanny cries, “you will certainly hurt yourself against those spikes; you will tear your gown; you will be in danger of slipping into the ha-ha.”

To give weight to her feeling of being trapped, Maria alludes to an incident in A Sentimental Journey, Laurence Sterne’s 1768 novel. The narrator, Yorick, is visiting the Bastille, thinking that imprisonment there might not be so bad. The prison, he muses, is just a kind of tower, and is a tower really so different from a house you can’t leave? Suddenly, he hears the same words repeated twice over—“I can’t get out—I can’t get out”—and looking up, sees a starling in a little cage. He tries to free the bird, but discovers the cage is locked in such a way that you can’t open it without destroying both cage and bird. All at once, Yorick is brought back to reality. “Mechanical as the notes were, yet so true in tune to nature were they chanted, that in one moment they overthrew all my systematic reasonings …”

Like the starling, Austen’s heroines cannot get out. At a very basic level, they’re trapped at home, isolated from the broader currents of life. Austen’s men—even her young men—have much more freedom. They can go to sea, travel abroad, attend college, even drive 32 miles to London for a haircut if they feel like it, as Frank Churchill does in Emma. Unmarried women, on the other hand, can’t even visit their neighbors without a chaperone. Judging by her letters, Austen herself, who never married, knew the tedium of rural domesticity first-hand: “Our dinner was very good yesterday, and the chicken boiled perfectly tender.” “The spectacles which Molly found are my mother’s.” “I understand that there are some grapes left, but I believe not many.”

Maria Bertram, like her sister Julia, is not exaggerating when she complains that her life is full of “restraint and hardship.” It doesn’t appear that way on the surface; after all, she’s beautiful, lively, and rich. But that doesn’t mean she’s free to go her own way. Like Austen’s other heroines, she’s a prisoner of the social code, constrained by her lack of choices, frustrated that, for reasons of social and financial security, she has to marry a man nobody even pretends to find attractive or interesting. Indeed, Maria’s wealth and spirit make things even worse for her, in that, unlike Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice, she’s not going to settle for an awful man because it’s the only offer she’s likely to get. Neither will she, like Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility, let go of her romantic idealism and come to accept a more prosaic suitor.

Before she’s bound forever to boring Rushworth, she wants a little adventure. She wants to flirt with the charismatic Henry Crawford, and who can blame her? After all, she’s only climbing over a gate; it’s not the end of the world. At least, this is how Maria sees it. She doesn’t realize that, in crossing over the ha-ha, she’s transgressing a symbolic as well as a physical boundary. The point of the ha-ha (rather than, say, an ordinary fence or wall) is that is isn’t visible from the house, ensuring a clear view across the estate (the ha-ha was so named because you don’t realize it’s there until—ha ha!—you come to it unexpectedly). A common feature of the 18th-century vogue for landscape “improvement,” it allowed the estate owner to keep livestock and peasants out of view without any break in the sightline. From the perspective of the house and gardens, the ha-ha cannot be perceived—an optical illusion. The ha-ha is an invisible barrier, a boundary line that seems all too easy to cross. Only when you find yourself in the middle of the wilderness do you realize the magnitude of what you’ve done.

Maria goes ahead with her marriage, but she can’t keep away from Henry; before long, their affair has rekindled, and the scandal sheets are full of it. Maria leaves Rushworth for Henry, but he won’t marry her, and rather than take her back, Rushworth sues for divorce. (This was easy enough for the husband of an adulterous wife, though a woman couldn’t get a divorce even if her husband beat her, was constantly drunk, and took a different mistress every week.) Maria is exiled from Mansfield Park in disgrace and even from England, sent to live abroad with a bothersome aunt. Does Fanny sympathize? On the contrary: “The greatest blessing to every one of kindred with Mrs. Rushworth,” thinks Fanny, “would be instant annihilation.”

Nobody likes “restraints and hardships,” but Fanny knows they keep the social order intact. Unlike Maria and Julia, Fanny doesn’t want to get out; she’s perfectly happy in her cage. Significantly, in the late 18th century, caged birds were often seen in English prints and drawings of women at home, engaged in music making or embroidery. The caged bird was a symbol of domestic contentment, of nature tamed and in its proper place. One might argue that even the starling, an uncanny vocal mimic, is in fact not unhappy with its life of restraint; after all, it knows no other experience—and, like Poe’s Raven, “what it utters is its only stock and store.” What Fanny knows, perhaps instinctively, is that our choices eventually become traps, just as our traps, if we stay in them long enough, end up feeling like home.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece named the wrong character from Sense and Sensibility and referred to a “piece” instead of a “bit” of ivory.