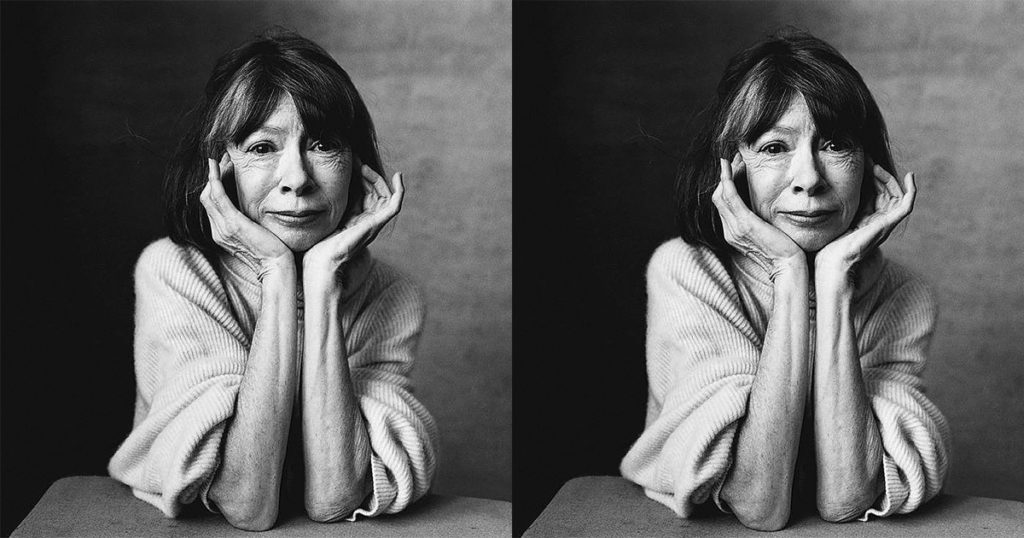

Joan Didion and the Magic of Grief

She went from cool customer to recorder of her own bereavement

Joan Didion, who died on December 23, wasn’t a feminist. In fact, she might have called herself an anti-feminist, considering her claim, in a 1972 piece in The New York Times, that the “women’s movement is no longer a cause but a symptom”—a symptom of childish, narcissistic thinking on the part of unrealistically discontented women who all dreamed of living a new life in the “Big Apple.”

Nevertheless, Joan Didion was feminist–which is to say aspirational, desirous, and passionately ambitious. Even as a young editor at Vogue, her then boyfriend testified, she would come home after a day studying word counts and women’s wear to spend half the night writing her first novel, Run, River (1963). And later, after she married John Gregory Dunne, she became a tough-minded, brilliantly observant journalist, who raced to the heart of the heart of every story. For instance, in perhaps her most famous piece, “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” from the 1968 collection of the same title, she was ecstatic to meet a five-year-old girl on LSD who confided that she went to “high kindergarten.” Sighed Didion on a film made by Dunne’s nephew years later, the discovery of that child was “gold, pure gold.”

But the Didion of the early journalistic books and short, sharp novels was transformed by grief. In The Year of Magical Thinking (2005), and later Blue Nights (2011), she became an astute reporter of her own bereaved consciousness and of the strange tricks mourning plays on us all when it becomes, as it did for her, electric. The disbelief in death—the myth of the return—seized her, as it has seized so many of us mourners. She confessed that she couldn’t give away her husband’s shoes because, what if he would need them? I know this feeling because it overwhelmed me on several occasions after my husband’s shocking and unexpected death 30 years ago. When a friend to whom I’d given some of his shirts (they were just my friend’s size) turned up for dinner wearing one of them, I berated him! What are you doing in my husband’s shirt?

The madness and misery of grief is what Didion so poignantly recorded. Yes, the medics who came to attend to her dead husband defined her as a “cool customer”—but now she had stopped being that person, at least on the page. Her journalistic attention to her own suffering—a suffering intensified by her daughter’s illness and impending death—was controlled by craft but remained white-hot, like a light that won’t go out. And the result, to mix metaphors, was “gold, pure gold.”