Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War, by Tony Horwitz, Henry Holt, 384 pp., $29

“Nothing so charms the American people as personal bravery,” John Brown once said. Unsurprisingly, then, after his 1859 attack on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry failed to trigger a slave insurrection, he and his harebrained plan have never wanted for detractors, hagiographers, or historians scratching their collective heads over the meaning of the man and his mission. Was Brown a lunatic or a liberator; a man of his time or ahead of it; a martyr without an ounce of racial prejudice or a crusader besotted by self-righteousness? Perhaps, even, he was a terrorist.

Early in his superb and amply researched new book, Midnight Rising: John Brown and the Raid That Sparked the Civil War, Pulitzer Prize-winner Tony Horwitz, author of Confederates in the Attic: Dispatches from the Unfinished Civil War, suggests that, indeed, the attack at Harpers Ferry seems “an al-Qaeda prequel: a long-bearded fundamentalist, consumed by hatred of the U. S. government, launches nineteen men in a suicidal strike on a symbol of American power. A shocked nation plunges into war.” Wisely, however, Horwitz then leaves present-day parallels behind.

Not only has Brown been the subject of countless biographies—by the likes of W. E. B. Du Bois, Oswald Garrison Villard, Stephen B. Oates, and most recently, David S. Reynolds, whose fine cultural biography appeared in 2005. Brown is behind the marching song that became the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and was the center of Stephen Vincent Benét’s epic poem, “John Brown’s Body” (1928), which Horwitz nimbly threads through his book. In calling Brown “a stone/A stone eroded to a cutting edge/ By obstinacy, failure and cold prayers,” Benét is likely drawing on W. B. Yeats’s more polished commemorative poem “Easter 1916,” in which the single-minded rebel “trouble[s] the living stream.” But, alas, “too long a sacrifice/ Can make a stone of the heart./ O when may it suffice?” When, indeed.

First, what happened: on the night of October 16, in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, Brown and 18 other men, including two of his sons, took control of the town’s bridges and rail lines, stopped a train, and seized the armory while two other conspirators kidnapped a pair of local slaveholders, a slaveholder’s son, and 10 slaves. A free-black baggage master at the depot was killed by one of Brown’s skittish men, posted on the railroad bridge, and Harpers Ferry, writes Horwitz, soon became “a virtual shooting gallery,” with townspeople firing potshots and vigilantes gunning down Brown’s men under flags of truce. Thirty-two hours later, after federal troops arrived, the town’s mayor lay dead and half of Brown’s 18 raiders had been captured, wounded, or killed. Also dead were Brown’s two sons, as well as, Horwitz drily notes, five black men, victims of “Brown’s war of liberation.”

Why the abolition of slavery became Brown’s raison d’être is not clear, though biographers typically point to Owen Brown, his abolitionist father, a devout Calvinist without much racial bias who traded amicably with the Indians. But Owen was a pacifist. His more martial son long remembered witnessing, as a boy, the beating with iron shovels of a young slave and wanting to fight in his defense. Yet Horwitz eschews facile psychologizing about Brown, except to point out that his mother died when he was only eight, and as Brown himself recollected, he “continued to pine” after her for years. Experiencing a series of personal disasters as an adult, including the death of his first wife after childbirth, the loss of four children to dysentery, and financial bankruptcy, Brown had, he wrote to a friend, a “steady desire to die,” tempered only by a wish to witness the destruction of slavery.

Remarried, the peripatetic Brown eventually moved his family to North Elba, New York. (Altogether, he fathered 20 children, nine of whom died before they reached age 10.) Philanthropist Gerrit Smith had donated acres of land there to black settlers, and Brown intended to live among and educate them, but in 1855, he could not withstand the call from the Kansas Territory. Proslavery and antislavery forces were battling for control of the legislature, and proslavery men from Missouri, the so-called border ruffians, habitually crossed the state line to vote in the Kansas elections. Brown and several sons entered the fray. In 1856, he was responsible for a massacre near Pottawatomie Creek of five proslavery settlers dragged out of their homes around midnight and butchered with broadswords.

During that year, Brown hatched his Harpers Ferry plan. Though he received financial support in the East from armchair abolitionists, he failed to entice Frederick Douglass, who thought the idea ridiculous, and ultimately enlisted only 21 followers, including three of his sons and a son-in-law.

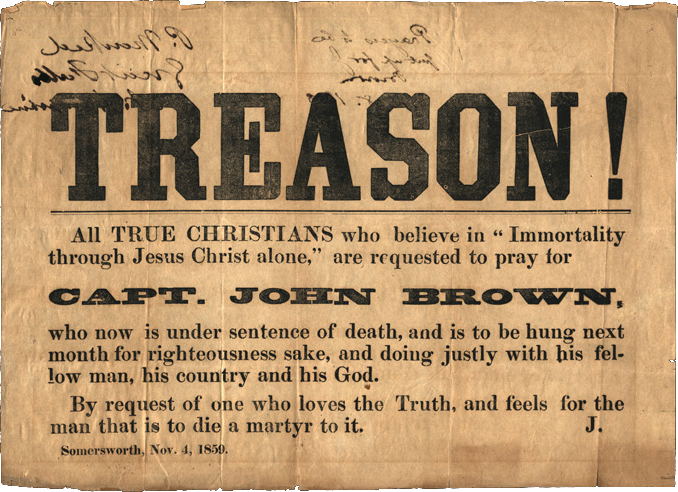

And Brown saw the plan through to its inevitable end. When Col. Robert E. Lee and his squadron of 12 U. S. Marines offered him a chance to surrender unconditionally before bashing down the door of the engine house where he and his men had holed up, Brown categorically refused. Stabbed with a decorative dress sword, he was taken prisoner, summarily tried, found guilty, and sentenced to hang.

He remained flinty, unrepentant—and eloquent. As Horwitz notes, Brown, who once used guns and pikes, now “deployed the spoken word,” and in converting his death sentence into a triumph with brilliant pith, he “cut through decades of cant and equivocation over slavery.” Thoreau said, “He could afford to lose his Sharpe’s rifles, while he retained his faculty of speech,—a Sharpe’s rifle of infinitely surer and longer range.” Emerson said that stony Brown “will make the gallows glorious like the cross.”

Could the systematic and violent enslavement of a people be ended only with violence? According to Frederick Douglass, “Slavery had so benumbed the moral sense of the nation that it never suspected the possibility of an explosion.” But if violence alone could rouse the country, did John Brown’s raid “spark” the Civil War, as Horwitz and, before him, David Reynolds contend? That too is debatable, though certainly the raid hardened the already-hard hearts of fire-eaters and secessionists and, as Horwitz notes, played to the fear of slave revolts that had obsessed the South since the days of Nat Turner. In the North, Brown’s lucidity and temerity turned him into a folk hero.

Could the systematic and violent enslavement of a people be ended only with violence? According to Frederick Douglass, “Slavery had so benumbed the moral sense of the nation that it never suspected the possibility of an explosion.” But if violence alone could rouse the country, did John Brown’s raid “spark” the Civil War, as Horwitz and, before him, David Reynolds contend? That too is debatable, though certainly the raid hardened the already-hard hearts of fire-eaters and secessionists and, as Horwitz notes, played to the fear of slave revolts that had obsessed the South since the days of Nat Turner. In the North, Brown’s lucidity and temerity turned him into a folk hero.

Yet Horwitz also points out gaping flaws in Brown’s scheme: his plan, which never stayed set for very long, was ill conceived from the get-go; he never tackled basic questions, like how to feed the flock of slaves who would presumably rush to his side; he never arranged to transport the huge cache of armory weapons he intended to seize; he never tried to seize them anyway; he never alerted any slaves of his intention; and he never budged from his untenable position in the engine house. Said Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of the New England writers who remained unenthusiastic about Brown, anyone with a modicum of sense “must have felt a certain intellectual satisfaction in seeing him hanged, if it were only in requital of his preposterous miscalculation of possibilities.”

Horwitz is gentler. As a novelist might, he renders with empathy and insight the lives of the individuals Brown touched, whether they were family members, victims, or the idealistic raiders who followed him to Harpers Ferry. Shot six times and surrounded by hostile Virginians, the captured raider Aaron Stevens declared, “one life for many,” and then looked longingly at the picture he wore around his neck of the girl he adored, a music teacher. Brown’s raiders thus appear more human, poignant, and fallible and the whole venture more noble, futile, benighted, heroic, and sadder than heretofore. Ditto the unlikable, unsinkable John Brown, a man of granite and stone, fixed to one purpose alone, who, as Yeats might say, troubled the living stream. Did his sacrifice, and that of his men, suffice? “That is Heaven’s part,” replies Yeats; “our part / To murmur name upon name.”