Since 2011, John Ryan Brubaker has split his time between Thomas, West Virginia, and Brussels, Belgium. His recent series, “On Confluence” and “Bakerstown Seam” have tackled issues like water pollution and the coal-mining industry in Appalachia. Here, Brubaker discusses the history of coal mining in a small town, the repercussions of resource extraction, and how a black square can represent the broader nuances of a political issue.

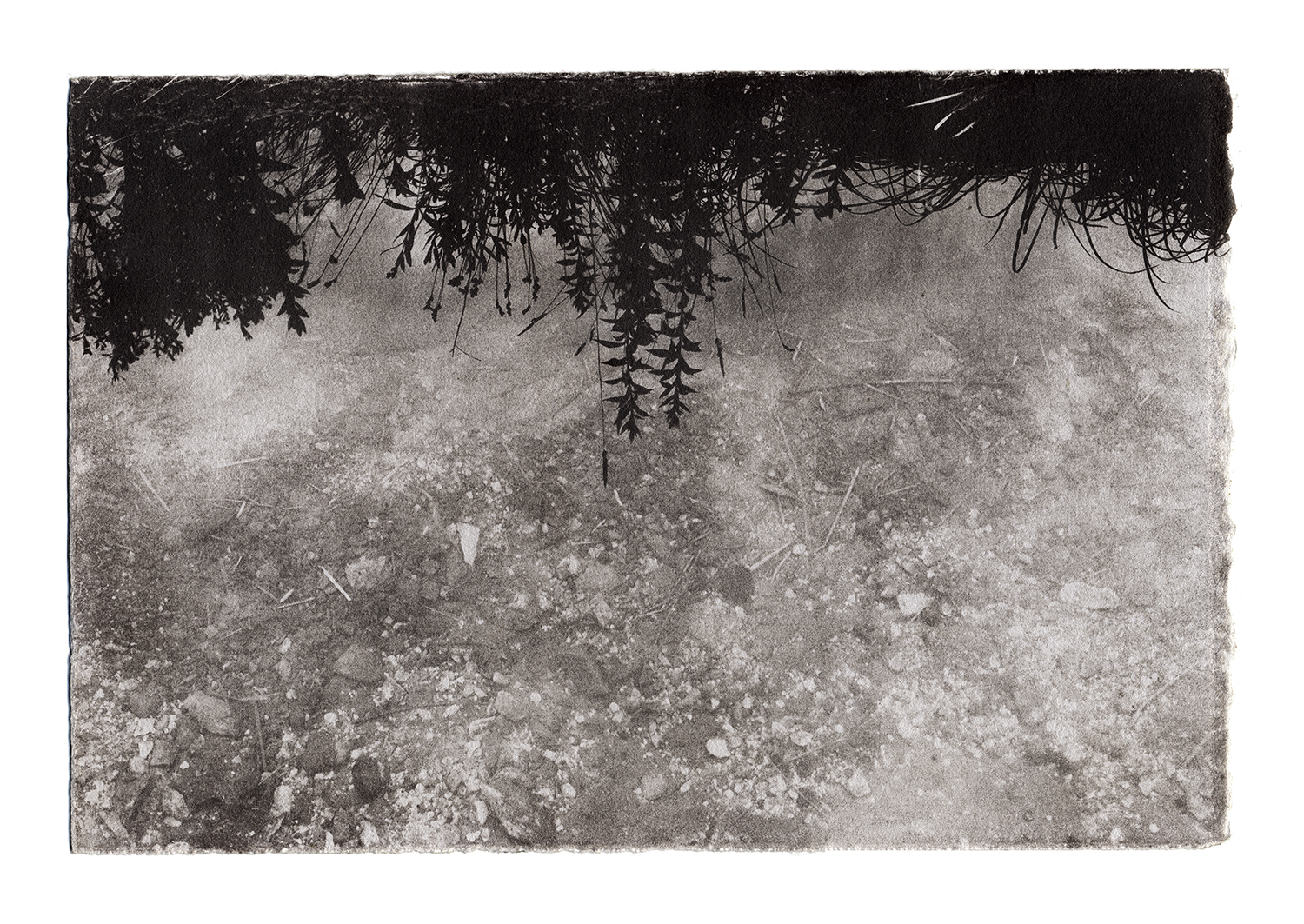

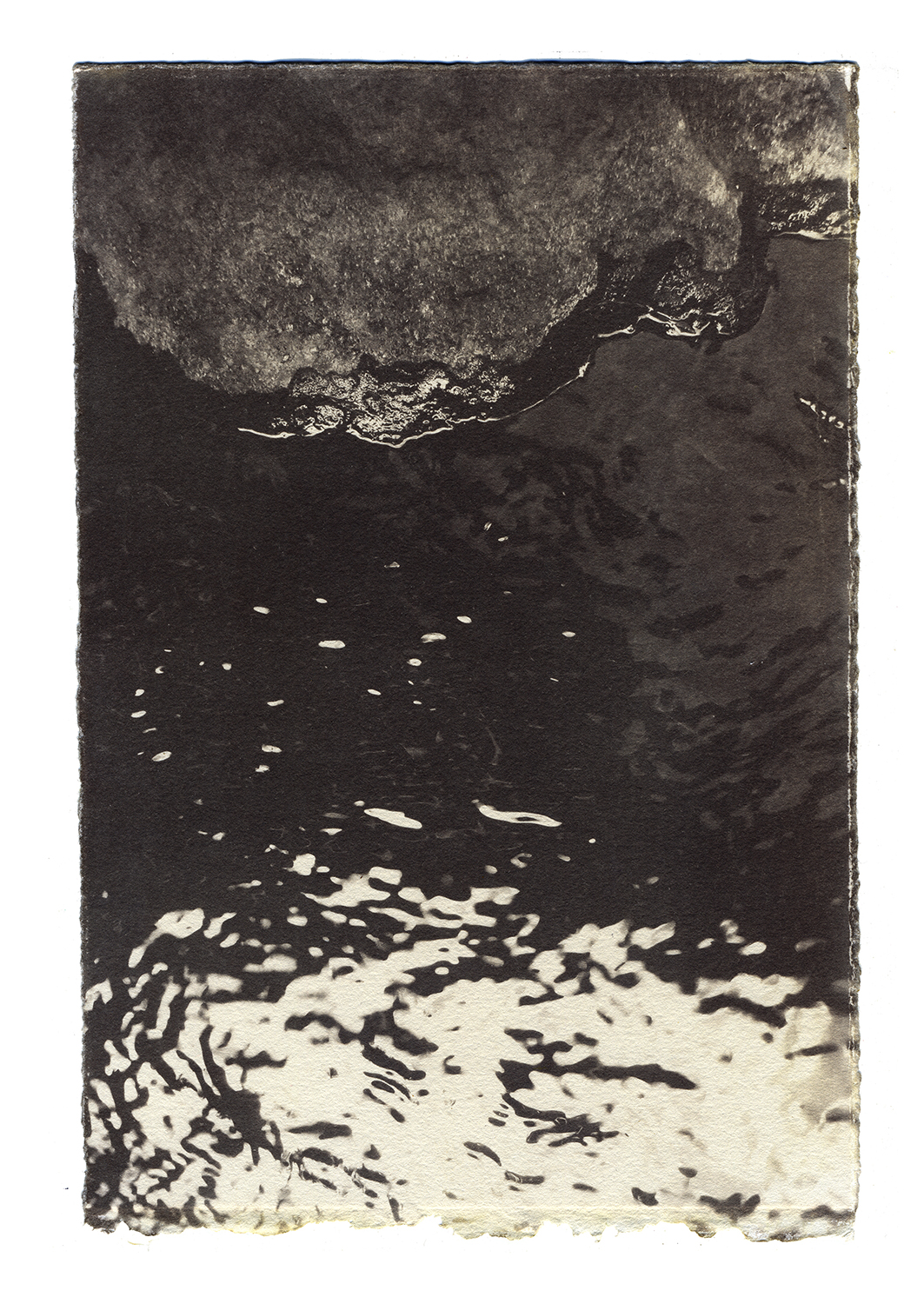

“For years, I’ve been making photographic series about movement through cities. I had a project called ‘Maps for Getting Lost’ in which I would walk around a city by following detour signs or cracks in the sidewalk—various absurd ways of navigating. Afterward, I would make photographic books based on the series of pictures that I took along the way. But in Thomas, it was difficult to maintain that practice—there are only a few blocks, so it’s hard to get lost. I decided to use the North Fork Blackwater River—which is across the street from my home—as my passageway. It’s polluted from acid runoff from underground coal mines. Under Thomas—a town of 500 people—there’s an 1,100-acre, water-filled mine-void. The water in it takes on heavy metals and then dumps something on the order of 200 million gallons a day into the river. I walked through the riverbed to get a feel for the state that the river is in—sometimes it’s clear, and sometimes it’s murky. I took photographs along the way, and then researched which parts of the river had the correct levels of pH for me to use to develop the photographs employing the Van Dyke printing method—a 19th-century process that uses acidic water as its developer, after exposing the negatives to sunlight. It was a conscious decision to engage the subject matter physically with the work. I look at this river pollution as a tiny example of what’s happening in other parts of the country, as well. Anywhere there’s this intense resource extraction, there’s always a hidden environmental impact.

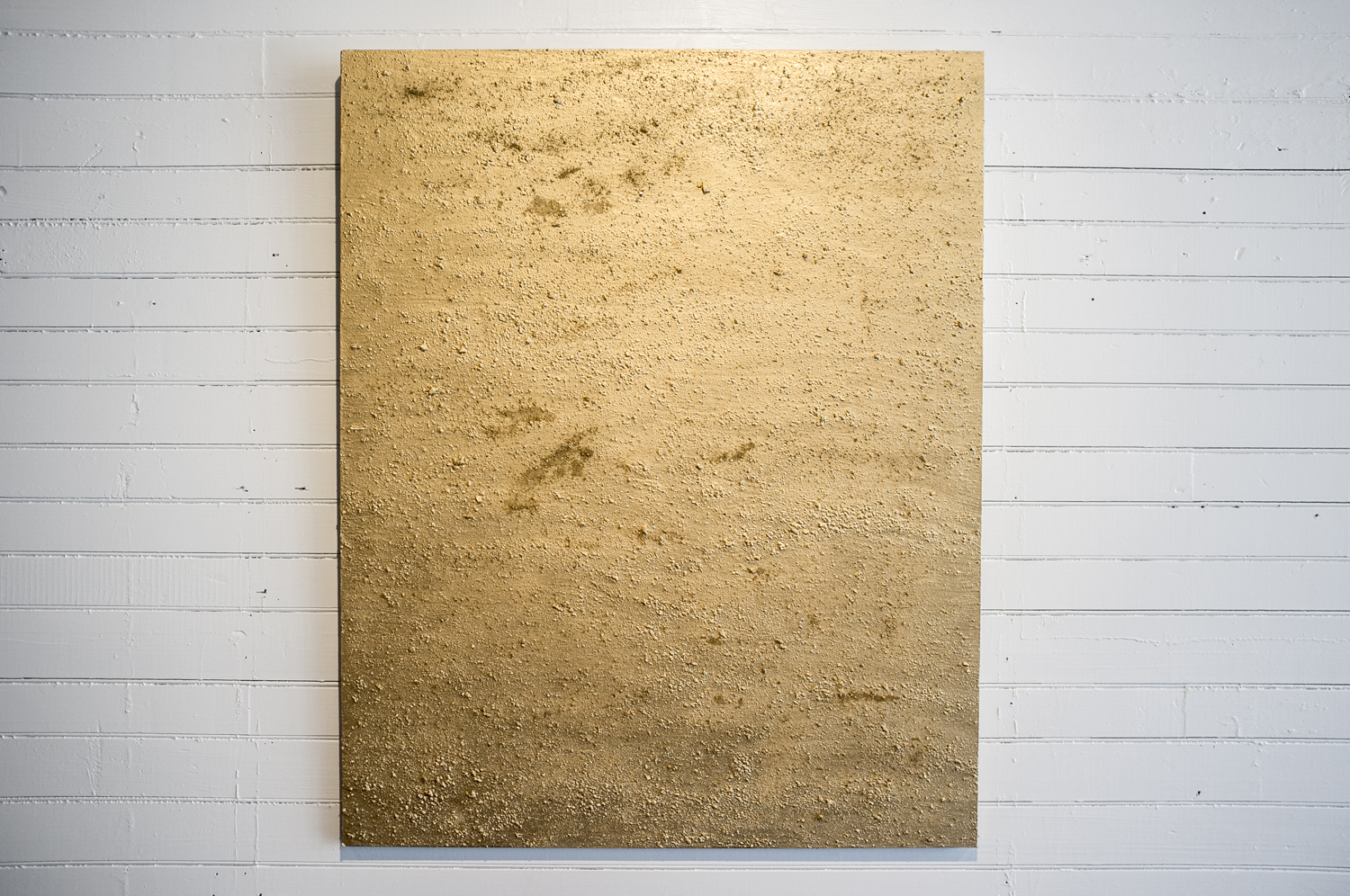

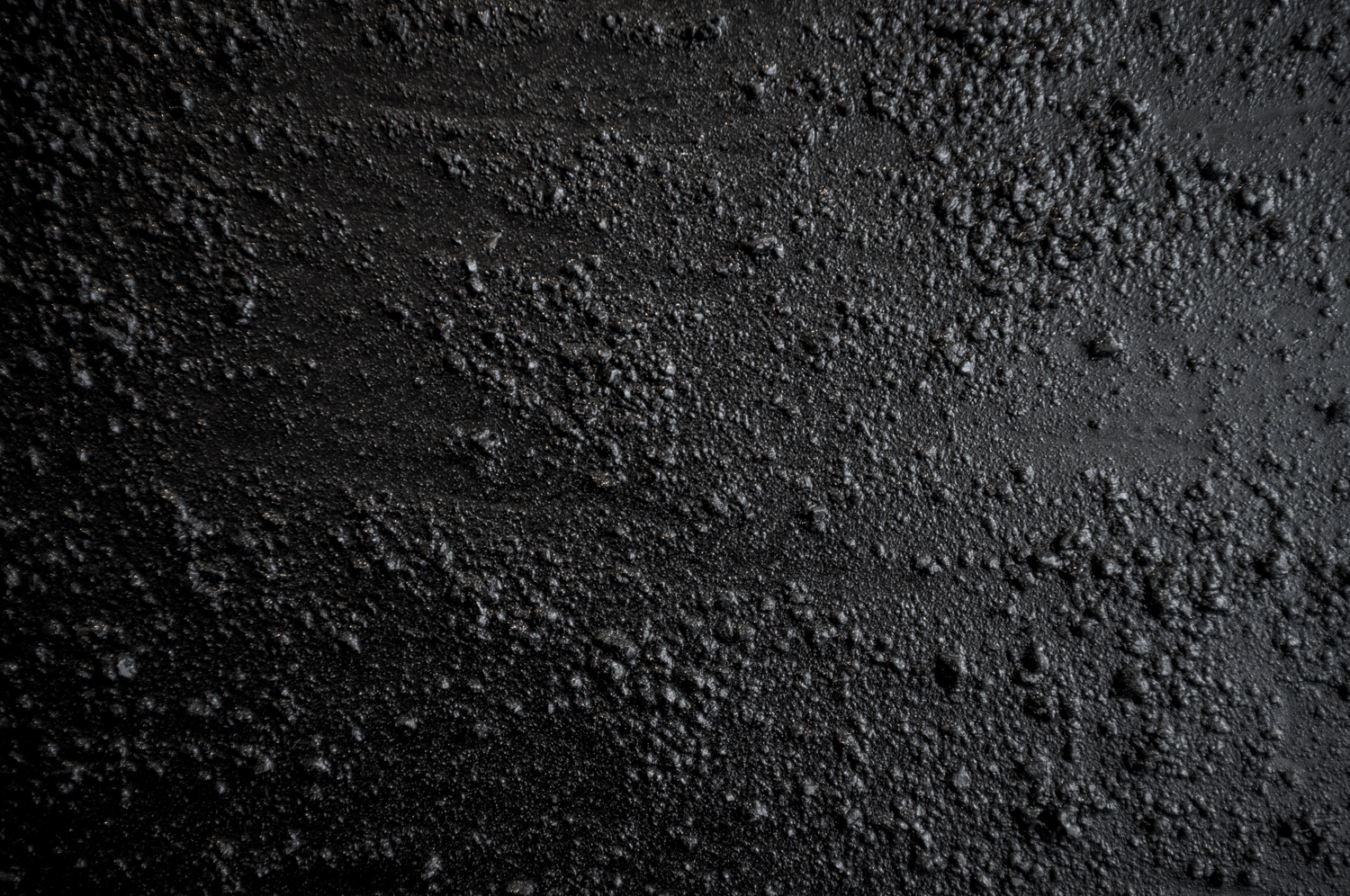

Throughout the process of the ‘On Confluence’ series, I constantly had coal on my mind as I learned more about the coal mining history of Thomas. Just walking around the riverbanks and through the woods, you find coal on the ground. There’s a coal seam that runs through the land, so I started bringing these chunks of coal back to my studio and was wondering what to do with them. I’ve been a strictly photography-based artist for 20 years, and I’ve never really made anything that wasn’t photographic. For the ‘Bakerstown Seam’ series, I ran the coal through an old meat grinder to turn it into dust, then mixed it with a gel-medium—which is acrylic paint without pigment in it—and made my own coal-paint. I started painting boards just solid black. This started about a year and a half ago, so this was after the 2016 election. I felt like I had to react as an artist, and it somehow seemed appropriate to paint things black. I was inspired by the artists working with black after World War II when the political and social climate felt incredibly heavy. At the moment, the paintings need to be about coal and not any kind of representation. When I show these pieces, it immediately brings up conversation about resource extraction and coal mining in Appalachia—both the cultural significance and the political debates surrounding it. These paintings let me talk about labor struggle in the United States and the price of coal on the market via large black squares.

Coal mining—as we think of it in the past—doesn’t really have a future in this region. Coal mining in West Virginia is now more often done by blowing the top off of mountains and scraping the coal out with machines. It’s a new phase of painful resource extraction in Appalachia. To me, it’s not a black-and-white issue. You can’t be simply against coal in Appalachia, because then you’re against intense parts of the culture here like the history of organized labor. The city that I live in wouldn’t exist without coal. I think it’s interesting how complicated it is. When people ask me how I feel, I say that I’m on the side of the coal miner but against the coal companies. This region was colonized by other parts of the country and it’s still recovering. Our governor is a coal baron in West Virginia; we almost had a Republican candidate here who just got out of jail because he was responsible for the deaths of coalminers. The coal industry is in the past, but it’s not gone. When I’m making these pieces, I’m trying to engage with that complicated history to learn about it and think about it, and have a more developed engagement with it via these conversations.”