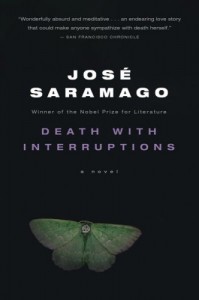

Ever since first reading José Saramago’s Death with Interruptions, I thought it would make a wonderful opera. A few years ago I had the chance to write a libretto and took the novel as its source. Its long, melodic sentences seemed to hang in the air like Bach’s sweetest melodies in slow 12/8 time. They are not singable as written, but I discovered they could be divided up to fit the human voice.

Ever since first reading José Saramago’s Death with Interruptions, I thought it would make a wonderful opera. A few years ago I had the chance to write a libretto and took the novel as its source. Its long, melodic sentences seemed to hang in the air like Bach’s sweetest melodies in slow 12/8 time. They are not singable as written, but I discovered they could be divided up to fit the human voice.

In the novel, death in a small Iberian country has decided to take a break. At first everyone is overjoyed, but soon the consequences of her decision become clear. In part two, she agrees to go back to work but only with new rules. Everyone will now get a week’s written notice of their impending end. Here my opera starts. One letter keeps comes back. Never in world history has someone not died on schedule. Death is flummoxed. She takes on human form, starts to investigate, and finds that her intended victim is a cellist. Death, now for the first time in a human body, fails repeatedly to deliver the message in person. She falls in love with her cellist and with his music. She goes to bed with him, and that day no one dies.

Saramago allows us to see how inhuman death is in ordinary life; if it had a body it could be seduced and known and would not be our death, implacable and incomprehensible. The cellist’s dog sits comfortably in her lap; it is the first warm thing death in human form has ever touched. Both are happy. The death of humans is not the death that deals with dogs.