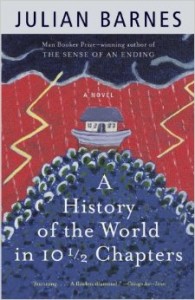

Julian Barnes’s A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters

A well-told story always feels true

An excerpt from A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters, first encountered in The New Yorker, changed how I thought about writing. Titled “Shipwreck,” it encompassed everything I desired from nonfiction, but found mainly in fiction: form, voice, imagination. Here, I thought, was a model for history as literature.

An excerpt from A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters, first encountered in The New Yorker, changed how I thought about writing. Titled “Shipwreck,” it encompassed everything I desired from nonfiction, but found mainly in fiction: form, voice, imagination. Here, I thought, was a model for history as literature.

It was unsettling, however, when I passed a newsstand and spotted the magazine cover with an ad heralding “new fiction by Julian Barnes.” How was this possible? The piece focused on a real painting, Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–1819), and offered countless verifiable details. But Barnes, I soon learned, was a novelist known for probing the boundaries between fact and fiction.

Around the same time, I read an article that described Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. as an historian and a writer. What was the difference, I wondered? Others, too, were contemplating the contours of historical writing, but the ensuing surge of professional discussion about nonfiction narratives quickly subsided. Academic historians have continued, for the most part, to produce scholarly studies lacking in literary art, while some non-academic writers offer creative works of nonfiction.

I regularly teach Barnes’s “Shipwreck.” At the end of class, I tell my students it is not history, but a work of fiction. Some look confused and some protest. But now they know that a well told story always feels true.