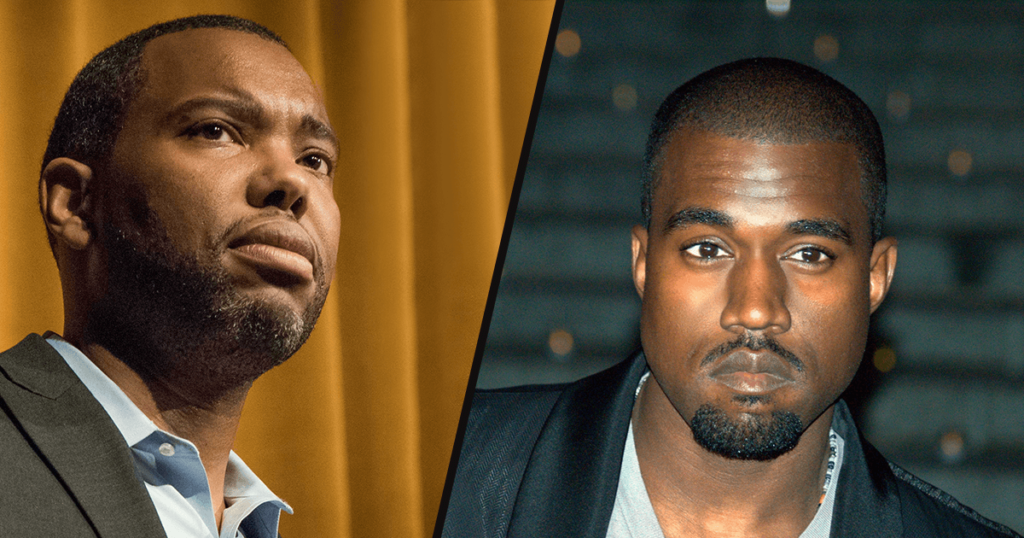

Yesterday Twitter was aflame with discussion of a new, 5,000-word essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates in The Atlantic. The piece, titled “I’m Not Black, I’m Kanye,” is a ferocious dressing down of the pop star that reiterates many of Coates’s abiding themes: history is not past; unflagging white supremacy is the source code that American software has always—and will always—run on; “racial identity” is—or is very nearly—something essential. The piece is a worthwhile read, and West is captivating—as are two digressions into the figure of Michael Jackson (whose skin condition and abusive family dynamics Coates reduces to wanting to be “white”) and the author’s own recent and personally destabilizing fame.

Coates is nothing if not engaging and thought-provoking, but reading this essay—much like reading “The First White President,” which he published in The Atlantic last year—left me feeling almost sickened. Without getting into the merits of West’s recent tweeting here, the larger question Coates’s piece raises is whether an individual can truly free herself from—or hope to transcend—the group identity into which she is born. (Asking why she might want to do so is another question.) For Coates the answer is a punishing no:

When Jackson sang and danced, when West samples or rhymes, they are tapping into a power formed under all the killing, all the beatings, all the rape and plunder that made America. The gift can never wholly belong to a singular artist, free of expectation and scrutiny, because the gift is no more solely theirs than the suffering that produced it. Michael Jackson did not invent the moonwalk. When West raps, “And I basically know now, we get racially profiled / Cuffed up and hosed down, pimped up and ho’d down,” the we is instructive.

What Kanye West seeks is what Michael Jackson sought—liberation from the dictates of that we.

Is Coates seriously arguing, as he seems to be, that the desire for “liberation from the dictates of that we”—or any we, any tribe!—is ipso facto a kind of moral violation? He claims for himself, here and elsewhere, a Mullah-like authority to assert communal possession of other people he deems to be a part of his community. And when those people deviate from what Coates pronounces to be the acceptable group perspective—“West calls his struggle the right to be a ‘free thinker,’ and he is, indeed, championing a kind of freedom—a white freedom”—he claims for himself the right, not merely to refute a person’s arguments but to deracinate them entirely.

More chilling than the essay has been the rapturous response it has generated among many white liberals who seem somehow too eager to reinforce its dire racial proscriptions. It is undeniable that West has gotten an astonishing amount wrong, but one thing he gets just right is this: Too many people of all persuasions act as though there are views, based on one’s perceived identity alone, that others must share. No matter what else might be said, that is an extraordinarily warped view of freedom.