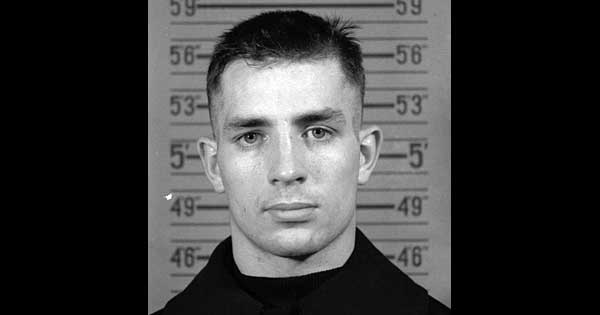

Kerouac in His Own Words

An old friend explores his search for a new approach to the novel

The Voice Is All: The Lonely Victory of Jack Kerouac, By Joyce Johnson, Viking, 512 pp., $32.95

Joyce Johnson’s new biography of Beat writer Jack Kerouac vies for room on a crowded shelf. Over the years, the literary industry surrounding Kerouac has produced several gems, among them Johnson’s own 1983 memoir, Minor Characters (winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award), which chronicled her affair with Kerouac and the lives of the other women who hitched themselves to the Beats—all the while holding down jobs, warming up pea soup, emptying ashtrays, suffering indifferent sex, and patiently awaiting the return of their wayward men. Part of the charm of Minor Characters was Johnson’s acknowledgment of how young and out of her depth she had been, a point made even more painfully clear in her letters to Kerouac, collected in Door Wide Open: A Beat Love Affair in Letters, 1957–1958.

Yet, with so much already said about Kerouac, Johnson’s latest effort struggles to justify itself. “For many years, I waited for a definitive biography of Kerouac to appear,” she writes in the introduction to The Voice Is All. “But I have come to wonder … whether there can be such a thing.” She then reviews her options. “One can emphasize the Beat aspect, while treating the ways Kerouac does not seem Beat at all as puzzling inconsistencies. … One can speculate on the nature of Kerouac’s sexuality; present a relentless chronicle of his drinking and dysfunctional behavior; call him a saint or a manic depressive; visit all the places he lived or to which he traveled and attempt to show that everything in On the Road or his subsequent ‘true life’ novels was true.” Does this mean Johnson will ignore the drinking and dysfunction? That she will rise above speculating on Kerouac’s sexual proclivities or the correspondence between fiction and fact? Not at all. In Johnson’s biography, we learn that Kerouac’s first wife aborted a black-haired baby that might have been Jack’s. Even the story of the notorious knifing death of David Kammerer by Kerouac’s friend Lucien Carr is filled out with new details.

Eschewing the unreliable anecdotes of others, Johnson tells us she has based her book entirely on “Jack’s own written words,” as well as the accounts of “his closest friends.” (As the above tidbits show, she has not quite ignored the minor characters.) Because all of this latter material has already been published and picked over, what remains is the Jack Kerouac Archive.

Eschewing the unreliable anecdotes of others, Johnson tells us she has based her book entirely on “Jack’s own written words,” as well as the accounts of “his closest friends.” (As the above tidbits show, she has not quite ignored the minor characters.) Because all of this latter material has already been published and picked over, what remains is the Jack Kerouac Archive.

Unlike fellow Beats William Burroughs and Gregory Corso, who hawked their manuscripts to see themselves through ragged times, Kerouac was a careful steward of his papers. In 2001, the New York Public Library’s Berg Collection acquired a massive collection of Kerouac’s notebooks, journals, diaries, letters, artworks, and manuscripts—selections from which were featured in a 2007 exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of On the Road’s publication. Released simultaneously was Beatific Soul: Jack Kerouac on the Road, collection curator Isaac Gewirtz’s generous and clear-eyed roadmap of Kerouac’s evolution as a writer. Though Johnson references many of the same documents and draws similar conclusions, she does not cite this work in her own account.

By Johnson’s lights, Kerouac discovered his “voice” on November 23, 1951, following an uproarious Thanksgiving Beat reunion. Yet, despite Johnson’s intentions, it is precisely Kerouac’s voice that is absent from her book, replaced by flat paraphrases from his journals, such as this one, describing a scene three years to the day before On the Road was hatched:

The weather was cool and bright that holiday weekend, with a sky of crystalline blue and early turning leaves that reminded Jack of October. As he walked through the streets of Ozone Park, where people were out in their yards grilling hot dogs and drinking beer— undoubtedly in a particularly celebratory mood because the war had just ended—Jack felt surrounded by the richness of American life. He was seized by the exhilarating urge to understand all of it and make it the subject of one huge novel. Then, as if a cloud passed over him, he felt that he was “alien” to all this richness he saw around him, that “none of it could be mine, only to express … all of [this] America, not for my likes, never,” since he was certain that nothing could eradicate the “Breton bleakness” in his blood that kept him an outsider. For the first time he called himself “half-American.”

And here is Kerouac’s actual entry:

Today, Labor Day, a clear sunny day with the tender blue char in the sky hinting of October. I felt a resurgence of the old feeling, the old Faustian urge to understand the whole in one sweep, and to express it in one magnificent work—mainly America and American life. Bunting, flying leaves, families drinking beer in their own backyards, cars filling the highways (the war being over officially now), children tanned and ready for school, the smell of roasts coming from the cottages on the leafy streets, the whole rich American life in one panorama. I had the feeling that I was alien to all this, as I walked around … that all this could never be mine to have, only mine to express. I felt like an exile. I told this to my mother, saying perhaps we were too French to be American, with a little too much of the bleak severe Breton in our lives and not enough emphasis on its fire and Celtic passion. … All of this, the cottages with laughter and good food and wine, the cars on the highways, the radios blaring, the flags and bunting—all of this, not for my likes, never. It’s strange, since I’m aware that I understand this far more completely than the people who do have the American richness in them.

There are no hot dogs, just the smell of roasts emanating from Ozone Park cottages. The leaves were not “turning” but “falling.” Nowhere does he say “half-American,” only “too French.”

But quite apart from these quibbles, there is the problem of paraphrase. Permission to quote from the unpublished work, Johnson explains, “remains restricted to writers whose projects have been sanctioned by the Kerouac estate.” Estates are often arbitrary in their dictates. Nonetheless, the reader of The Voice Is All is subjected to long fugues of neutered paraphrase, far from “Jack’s own written words,” and far too little shaping narrative and historical context. This becomes particularly acute when one is trying to absorb the sea of names of the ever-widening Beat circle, not to mention those of fictional characters, many of whom never saw the light of day. But it is when Kerouac writes of his tortured struggle to find a new “method”—he doesn’t use the word voice—that the insufficiency of Johnson’s own method becomes apparent. At such times, one imagines young Joyce in the back seat of a car smiling grimly with Jack at the wheel, careening between moods and women and abruptly abandoned manuscripts—as if she is still, in part, the girlfriend trying to domesticate a story that keeps veering away from her.