1. One of the above is a kiki, the other a bouba. Which shape is which?

2. Consider two cups—or, if you’re feeling unimaginative, bring out real ones. Fill one cup with carbonated water, the other with tap water. Drink. Now match each cup of water to one of the shapes.

3. Now consider three samples of chocolate. One is milk chocolate, and the other two are dark—70 percent and 90 percent cocoa. Nibble. Again, assign each to a shape.

Chances are good you matched the word bouba to the rounded shape on the left and kiki to the spiked one on the right. Dubbed the “bouba-kiki effect” by folks who presumably enjoy appearing foolish at departmental functions, the phenomenon is well known to linguists. Across multiple studies, with participants from different cultures, boubas (and other words formed with the so-called “rounded” vowels in boo or bow) are linked to smooth, curvaceous objects, while kikis (and similar words) are associated with jagged angles and objects sharp to the touch.

The phenomenon starts young: toddlers also experience the “bouba-kiki” effect. Recently a study by New York University researchers Ozge Ozturk, Madelaine Krehm, and Athena Vouloumanos demonstrated that four-month-olds—we’re talking about babies who haven’t yet attached meanings to simple words like banana—already show more interest in stimuli that aren’t consistent with adults’ sound-shape correspondences (e.g., when kiki is paired with a curvy shape) than in stimuli that are.

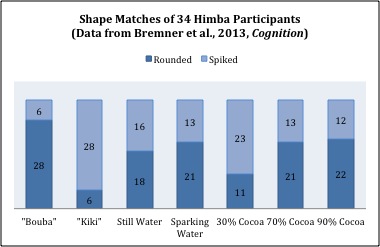

Data from questions two and three, albeit sparser, suggest that Western taste-buds link carbonated water, as well as very dark chocolate, with angular shapes. But here the story gets complicated: Namibia’s Himba people—who are semi-nomadic, without written language, and in possession of “one of the most remote cultures from Western (or Eastern) cultural influence remaining,” according to a new study by Andrew Bremner of Goldsmiths and his colleagues—behave quite differently.

As you can see, while the Himba show the tried-and-true, infant-proof “bouba-kiki” effect, they don’t appear to assign carbonation to one shape over the other. And while the Himba matched chocolate samples to shapes with a consistency we would not expect by chance, they did so in the opposite direction of Westerners.

Some associations between senses in different modalities—words and shapes, even digits and colors—are either innate or involve aspects of the world so universal and obvious that, by very young ages, everybody everywhere reaches the same conclusions about them.

But for others we’re left guessing. Is it San Pellegrino’s star-shaped logo that’s responsible for the link between pointy shape and fizzy water? Or perhaps the sourness of the carbonation—its sharpness, if you will? Or does this relationship dwell in a verbal realm, with words like “sparkling” and “spiked” serving as mediator between taste and shape? (Let’s leave for another day the chicken-egg question of how these words came to have the meanings they do.)

We like to think that our thoughts are our own. But the “bouba-kiki” effect and its brethren remind us that even our innermost frivolities—the individual tastes and intuitions we enjoy exercising when we search for the right paint color for the kitchen or brainstorm band names or decide on a brand of orange juice—may not be that individual at all. (We’ve all encountered parents who tried so hard to find the perfect not-weird-but-unique baby name only to find, come preschool, that their son is one of seven Sebastians.) We’re left, instead, with a startling uncertainty about where our own quirks end and those of others—within our culture or outside it—begin.