“Kindly nervous” was my father’s euphemistic term for the immense anguish he suffered periodically from bipolar illness, or “manic depression,” as it was then called. Unfortunately for him, the manic phase was no fun—no wild sprees, no elation. Instead, he just worked harder than ever at the dimestore, where he spent most of his time anyway. When Daddy’s mania increased to the point where he could no longer sleep, sometimes I accompanied him down to the store, sleeping on a pallet under his desk while he worked all night long, then going out with him into the chilly dawn to a greasy spoon for breakfast. How I loved those breakfasts! I got to order scrambled eggs and my own big white ceramic cup of sweet, milky coffee while sitting alongside early-morning truckers and the miners who’d just worked the graveyard shift, their eyes rimmed with coal dust like raccoons.

But these weeks of intense activity would lead to scarier behavior, as he became increasingly jumpy and erratic. I remember one time when Daddy had taken me to the golf course in Tazewell, Virginia, near our hometown of Grundy. I tossed him a putter when he wasn’t expecting it, then was terrified when he screamed and fell down flat, writhing in tears on the putting green. Before long would come the inevitable downward spiral. He’d talk less and less, stay in bed more and more, and finally be unable to go to the dimestore at all.

Then my Uncle Curt or my cousin Jack or another family member would come and drive him away to the hospital—sometimes the state mental hospital over in Marion, sometimes an out-of-state facility. My father was lucky because he was in business with several men in his family who were willing to oversee the dimestore and take over his other responsibilities whenever he became kindly nervous and had to “go off” someplace to get treatment, since there was no mental health care—none at all—available in Buchanan County.

After I married and moved to North Carolina, my husband and I brought my father down to Duke University Hospital in Durham, very near us in Chapel Hill. I remember visiting him there once, in his third-floor room of the mental hospital wing, which overlooked the famous Duke Gardens, then in full bloom. He was not looking out at the gardens, though. Instead, I found him staring at a sheet of paper with something drawn on it.

“What’s that?” I asked.

He replied that his doctor had left paper and pencil for him to draw a picture of a man doing something he enjoyed.

I looked at the stick figure. The man’s hands hung straight down from his tiny hunched shoulders; his legs were straight parallel lines, up and down; his round head had no face, no features at all. None.

“So what’s he doing?” I asked.

“Nothing,” my father said.

In the fierce grip of severe depression, this popular, active, civic man—a great storyteller, a famous yellow-dog Democrat, a man who never knew a stranger—could not imagine doing anything, not one thing in the entire world, that he might enjoy.

But the worst part was that he was always embarrassed about his illness, never understanding that it was an illness, but regarding it rather as a weakness, a failure of character, which made him feel even worse. “I can’t believe I’ve gone and done this again,” he’d say. “I’m just so ashamed of myself.”

[adblock-right-01]

I will never forget what a breakthrough it was for him when I gave him William Styron’s just-published book Darkness Visible, a memoir of Styron’s own depression. My dad respected Styron; he had read The Confessions of Nat Turner and had heard Styron speak at a literary festival at my college. Daddy read Darkness Visible in one sitting.

“I can’t believe it!” he said. “I can’t believe he would tell these things!”

Styron had laid it on the line:

The pain of severe depression is quite unimaginable to those who have not suffered it, and it kills in many instances because its anguish can no longer be borne. The prevention of many suicides will continue to be hindered until there is a general awareness of the nature of this pain. … Depression afflicts millions directly, and millions more who are relatives or friends of victims. … As assertively democratic as a Norman Rockwell poster, it strikes indiscriminately at all ages, races, creeds and classes.

My mother, too, was hospitalized for depression and anxiety several times, mainly at Sheppard Pratt in Baltimore, but also at the University of Virginia Hospital in Charlottesville. She often attributed those bouts to “living with your father”—and undoubtedly there was some truth to this—but the fact is that she came from a kindly nervous family herself. Her father and a brother both committed suicide; another brother, my Uncle Tick, was a schizophrenic who lived at home with my grandmother, and later in the VA Hospital. An older cousin, Katherine, had died at the state mental institution in Staunton, Virginia, where she had been hospitalized because she was “oversexed.” (I never knew this cousin had existed until many, many years later.) But I knew that Mama’s beloved niece Andre was also in and out of the hospital in Washington frequently, suffering from schizophrenia. She died alone, too young, in her own apartment.

No wonder Mama and her sisters frequently took to their beds—just lying down wherever they lived, it seemed to me—whenever life got to be too much for them. Would I just lie down, too, I worried, when the time came? To counter this possibility, I was a whirlwind of energy.

When Mama got sick, she was physically sick, too—with stomach problems, insomnia, migraine headaches, and other undiagnosed pain. She ate very little and got very thin, subsisting on things she thought she could tolerate, such as rice, oatmeal, milk toast, and cream of wheat, which were all supposed to be easy on the stomach. In my memory, my mother’s food was entirely white. She had a special daybed downstairs next to the kitchen, where she’d stay more and more. During those episodes, our housekeeper, Ava McClanahan, came every day to take care of Mama and the house. Daddy did all the shopping. This could go on for a long time. Sometimes Mama and I would be taken up to stay with my Aunt Millie and Uncle Bob in Maryland for a while. Other times, she went into the hospital.

[adblock-left-01]

This is my story, then, but it is not a tragedy. Whenever either of my parents was absent, everybody—our relatives, neighbors, and friends—pitched in to help take care of me, bringing food over, driving me to Girl Scouts or school clubs or whatever else came up. People loved my parents, and in a mountain family and a small, isolated town like Grundy, that’s just how people were. In times of trouble, they helped each other out. Also, I had my intense reading, and my writing, and usually a dog to keep me company.

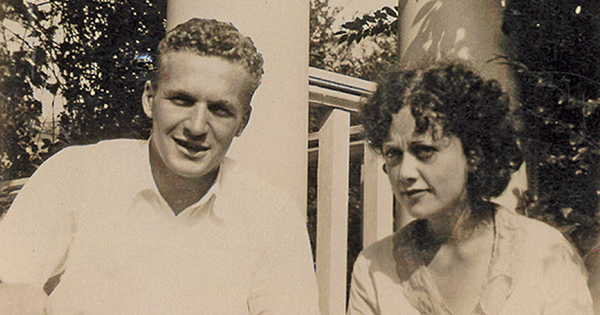

All their lives, my parents were kind, well-meaning people—heartbreakingly sweet. Because they did not understand their problems as illnesses, they did not blame each other for them. Nor did they involve me in any way, other than trying to make sure that I would “get out” of whatever it was that they were “in.” I loved Grundy. But they were adamant, sending me away to summer camps and then to preparatory school, where they felt I would have “more advantages.” Or maybe I was just too much for them, too lively, this child who came along so late in their lives.

Only once, the year I was 13, did my parents’ hospitalizations coincide, when my father was at Silver Hill in Connecticut while my mother was in Charlottesville, and so I was sent to live with my Aunt Millie in Maryland. She enrolled me in a nearby progressive, experimental private school named Glenelg Country School, where a friend of hers taught English. With 30 or 40 students at most, Glenelg was situated in a grand old house—a mansion, I thought at the time—surrounded by rolling fields. We called our teachers by their first names, meditated each morning, memorized a lot of poetry, and played a game I had never even seen before, called field hockey, with curved sticks. Everybody said I talked funny, but I thought they talked funny, too. I made some new friends and got to ride their horses, which I loved.

While I was there, I received an invitation from my mother’s psychiatrist, Dr. Ian Stevenson, who proposed to take me out to lunch the next time I rode the train down to visit my mother. In retrospect, this luncheon appears to me highly unusual, and I am surprised that my overanxious Aunt Millie even allowed it. She customarily arranged for me to spend the night in Charlottesville with an old family friend whenever I went to visit Mama in the hospital. Neither the family friend nor my Aunt Millie had been invited to lunch. But Dr. Stevenson was a well-known and respected physician, the new head of the department of psychiatry at the University of Virginia. He specialized in cases of psychosomatic illness, which must have included my mother.

Later, Dr. Stevenson would become famous for his interest in parapsychology, especially reincarnation. He thought that the concept of reincarnation might supplement what we know about heredity and environment in helping to understand aspects of behavior and development. He was especially interested in “Children Who Remember Previous Lives,” the title of a book he would publish in 1987. But if Dr. Stevenson had any curiosity about my own past lives, he kept mum about it. Our luncheon remains one of the most memorable occasions of my youth.

He met me at the train station, holding a pink rose, which he presented to me as he bowed. Dr. Stevenson was a tall, angular man, all dressed up in a suit, vest, and tie. I was all dressed up, too, in my pleated plaid skirt, navy blue jacket, and Add-a-Pearl necklace. Dr. Stevenson put me and my little bag into his big, shiny car and took me to a fancy restaurant with linen tablecloths, up on a hill. He invited me to order anything I wanted from the largest menu I had ever seen. I chose lemonade and a club sandwich, which arrived in four fat triangles with a little flag stuck into each one, plus curly potato chips and pickles. I ate every bite.

Dr. Stevenson said that he had heard a lot about me from my mother, and he had wanted to meet me because he thought that I must be an interesting little girl. He asked me a lot of questions about my new school, and what books I liked to read, listening very carefully to my answers. I had just read Jane Eyre twice, cover to cover. Dr. Stevenson nodded as if this were the very thing to do. I loved poetry, I told him. Then I recited the poem we had just learned, “Breathes there the man with soul so dead, / Who never to himself hath said, / ‘This is my own, my native land!’ ” I took a deep breath and followed that one up with “Annabel Lee” in its entirety. Nobody could have stopped me.

“It sounds like a wonderful school,” Dr. Stevenson said, smiling. Then he leaned forward intently and said, “Lee, since your parents are both ill, I wonder if you have ever worried about getting sick as well.”

“You mean, if I am going to go crazy, too,” I blurted out.

“Yes,” he said, “if you are going to go crazy, too.”

I stared across the table at him. How did he know? Because that was exactly what I thought about, of course, all the time.

“Yes!” I said.

“Well, I am a very good doctor,” he said, “and you seem to me to be a very nice, normal little girl, and I am here to tell you that you can stop worrying about this right now. So you can just relax, and read a lot more books, and grow up. You will be fine.”

I sank back in my chair.

“Now,” he said, “would you like some dessert?”

“Yes,” I said.

The waitress brought the giant menus back.

I ordered baked Alaska, which I had never heard of, and was astonished when it arrived in flames. The waitress held it out at arm’s length, then set it down right in front of me. It looked like a big fiery cake. “Oh no!” I cried, scooting my chair back. Everybody in the restaurant was pointing and laughing at me. Even Dr. Stevenson was laughing.

“You’re supposed to blow it out,” the waitress said.

I tried, but the more I blew, the higher the flames went and the more they jumped around. I felt like I was at some weird birthday party where everything had gone horribly wrong. “I can’t,” I said finally. Dr. Stevenson stood up, his expression changing to concern. Out of the corner of my eye, I could see waitresses and kitchen staff converging on our table. I could feel the heat on my face. I blew and blew, but the baked Alaska would not go out.