King, Kennedy, and the Power of Words

How candor and poetry can change the course of history

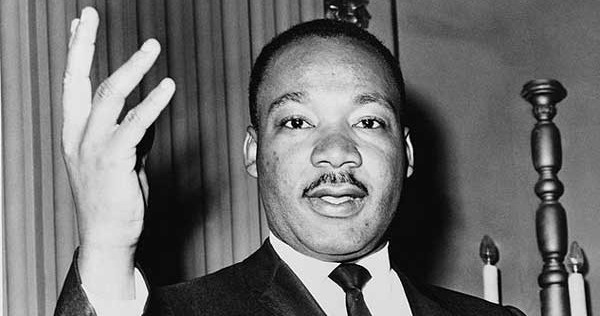

The night of April 4, 1968, presidential candidate Robert Kennedy received the news that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated. Kennedy was about to speak in Indianapolis and some in his campaign wondered if they should go ahead with the rally.

“Do they know about Martin Luther King?” Kennedy asked those gathered on the platform. No, came the reply.

After asking the crowd to lower its campaign signs, Kennedy told his audience that King had been shot and killed earlier in Memphis. Gasps went up from the crowd and for a moment everything seemed ready to come apart. Indianapolis might have joined other cities across America that burned on that awful night.

But then Kennedy, beginning in a trembling, halting voice, slowly brought the people back around and somehow held them together. Listening to the speech decades later is to be reminded of the real power of words. How they can heal, how they can still bring us together, but only if they are spoken with conviction and from the heart.

Later on, Kennedy recited a poem by Aeschylus, which he had memorized long before that trying night in Indianapolis:

Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget

Falls drop by drop upon the heart,

Until, in our own despair, against our will,

Comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.

Kennedy’s heartfelt speech came only hours after King’s last address. The night before, the civil rights leader had reluctantly taken to the dais at the Mason Temple in Memphis. The weather that evening had been miserable—thunderstorms and tornado warnings. As a result, King arrived late and was just going to say a few words and then tell everyone to please go home.

Visibly tired and with no notes in hand, King stumbled at first. The shutters hitting against the temple walls sounded like gun shots to him. So much so that King’s friend, the Rev. Billy Kyles, found a custodian to stop the noise. Only then, at the crowd’s urging, did the words begin to come together for King.

King closed by telling the crowd, “… we as a people will get to the Promised Land. So I’m happy tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. …”

Novelist Charles Baxter contends that the greatest influence on American writing and discourse in recent memory can be traced back to the phrase “Mistakes were made.” Of course, that’s from Watergate and the shadowy intrigue inside the Nixon White House. In his essay, “Burning Down the House,” Baxter compares that “quasi-confessional passive-voice-mode sentence” to what Robert E. Lee said after the battle of Gettysburg and the disastrous decision of Pickett’s Charge.

“All of this has been my fault,” the Confederate general said. “I asked more of the men than should have been asked of them.”

In Lee’s words, and those of King and Kennedy, we hear a refreshing candor and directness that we miss today. In 1968, people responded to what King and Kennedy told them. During that tumultuous 24-hour period in 1968, people cried aloud and chanted in Memphis. Words struck a chord in Indianapolis, too, and decades later former mayor (and now U.S. Senator) Richard Lugar told writer Thurston Clarke that Kennedy’s speech was “a turning point” for his city.

After King’s assassination, riots broke out in more than 100 U.S. cities—the worst destruction since the Civil War. But neither Memphis nor Indianapolis experienced that kind of damage. To this day, many believe that was due to the words spoken when so many were listening.