Ku Klux Khaki

The far right’s signature style is less about dad pants and more about fatherhood

On a bitter Friday morning in late January, dozens of men belonging to Patriot Front, which ProPublica has called “perhaps the most active white supremacist group in the nation,” assembled in downtown Washington, D.C., near the National Mall. As it had done in years past—and as it had done just two weeks earlier in Chicago—the group was trolling for publicity alongside the larger anti-abortion March for Life. The men moved up Constitution Avenue in a loose column, under a large sign proclaiming that “Strong families make strong nations” and behind an imposing police cordon. Some carried riot shields, others waved American flags, and all dressed in what has become the signature uniform of the far right: brown boots, khaki pants, navy-blue jackets, and khaki baseball hats, plus leather work gloves, sunglasses, and white balaclavas that obscured their faces and made them look like uniform-store mannequins that had reluctantly come to life. The pack stopped in front of the National Archives, where a banner advertised an exhibition called “Rightfully Hers: American Women and the Vote.” Silently, they handed out glossy postcards: “America belongs to its fathers, and is owed to its sons.”

After the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in August 2017, where many white nationalist groups turned out in khakis and polo shirts, commentators observed that contemporary American hate favors an unnervingly familiar style: suburban-dad chic. Hoods and robes are out. So are face tattoos and grimy cutoffs, and even, in many cases, the burly tactical gear of militiamen. As GQ, Vice, and other fashion-conscious publications noted, the new look pulls together “all-American” staples to dress white supremacy in a uniform of relaxed-fit power and respectability.

Most analysis has focused on the aesthetics of the clothes themselves, but khaki pants and blue shirts also come with historical baggage. An Urdu word meaning dust-colored, khaki was first used in English in 1846 to describe uniforms worn by British troops fighting to suppress colonial rebellions in India. The style gained popularity among civilians in the United States after World War II, but it became “all-American” well before that. The U.S. Army first adopted khaki in the 1880s for cavalry units fighting Native Americans in the West. Light-brown canvas fatigues helped camouflage cavalrymen in arid landscapes, as well as the mud and manure stains that often streaked traditional blue uniforms.

At the start of the Spanish-American War in the spring of 1898, the Army ordered khaki for general use in the tropical heat of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. Yet supply shortages meant that most American infantrymen went into battle wearing wool, leading to many casualties from the heat. Mounted units including Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders were among the few outfitted with khaki pants and hats, which they wore in Cuba along with traditional blue shirts.

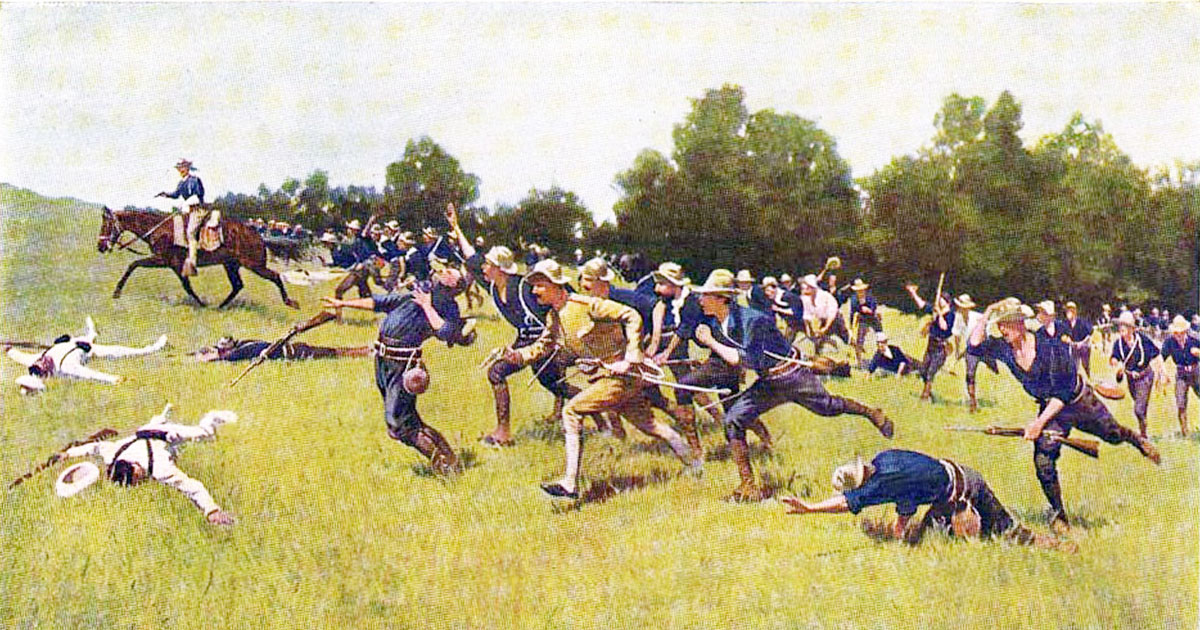

Viewed in a certain light, Frederic Remington’s paintings of the Rough Riders taking San Juan Hill now look uncannily like studies in Patriot Front colors. This is unlikely to be a coincidence: the group counts hiking among its activist outings, and its founder, Thomas Rousseau—a former Boy Scout who styles himself online as an amateur historian—often accessorizes his uniform with a neckerchief like the one Roosevelt wore in images from his Cuban campaign.

But Patriot Front’s choice of outfits highlights a deeper link between white nationalism and “dad pants,” as i-D magazine dubbed them, one less about the pants and more about who wears them. Khaki was the uniform of Indian Removal and American imperialism, but it was white fatherhood that provided the ideological foundation for wars of conquest in the West and overseas. Invoking fathers and sons, Patriot Front claims this inheritance as its own, arguing that “American identity was forged in a struggle between civilizations that ended in victory for our ancestors.” This idea of a patrilineal European-American birthright underpins the group’s sprawling agenda, framing their anti-Black, anti-immigrant, anti-gay, anti-abortion politics as paternal stewardship—a duty to preserve a hereditary entitlement for the next generation. Yet a closer look at the role of white fatherhood in American history puts the idea of such an ancestral “victory” into doubt, revealing a much more mixed—and arguably more ominous—legacy.

Charge of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill (1909) by Frederic Remington (Wikimedia Commons)

From their earliest encounters in North America, Europeans called Native Americans “savages” and “heathens,” while Native Americans commonly referred to European powers and their representatives as “father” or “great father” as a diplomatic strategy. They wanted from Europeans what they knew fathers give: respect, aid, and protection when necessary.

Europeans adopted the honorific but gave it a different significance. They were well prepared to hear in the title “father” that Native Americans were their children—their inferiors. Classical Athenian political traditions said fathers were naturally superior, meant to govern the household and the body politic alike. Christian myth and doctrine held fathers to be all-powerful and infallible, saving or damning as deserved. Emerging Enlightenment race science proposed that Native Americans occupied a lower order of human development—but also that they could be taught and assimilated into European civilization, unlike Africans.

After the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Thomas Jefferson took this logic a step further, and in the process became probably the first person to be called “Great White Father.” The phrase shows up in an 1806 translation of an Osage song reportedly composed after a visit to the White House. Jefferson explained to the Osage people that the United States had inherited its role as their father from the European empires it supplanted, and now intended to hold the title in perpetuity. “Never more will you have occasion to change your fathers,” he assured them.

In the hundreds of thousands of acres acquired from France, tribes such as the Osage were vastly more numerous and powerful than white settlers. By embracing the role of the supreme patriarch, Jefferson hoped to discourage Native Americans from allying with Europeans reluctant to give up their claims to land and resources that now belonged to the United States, and from becoming entangled in conflicts with other tribes that might invite European meddling. Instead, he wanted them to blend in quietly to the nation now claiming dominion over theirs, by remaking themselves as yeoman farmers.

“My Children,” Jefferson addressed a group of Cherokee who petitioned for citizenship in 1808, “Have you the resolution to leave off hunting for your living, to lay off a farm for each family to itself, to live by industry, the men working that farm with their hands, raising stock or learning trades as we do, & the women spinning & weaving Clothes for their Husbands & Children?” This form of family life was to be learned, Jefferson made clear, before citizenship, with all its benefits, could be conferred.

Though many Cherokee did as Jefferson advised and took up settled family farming, these efforts were not met with the promised rewards. Andrew Jackson claimed he was fulfilling his duty to his “red children” when he pushed through the Indian Removal Act in 1830. Facing expulsion from Georgia, the Cherokee brought a suit against their removal to the Supreme Court in 1831. Chief Justice John Marshall used the fact that they called the president “Great Father” as evidence that their “pupilage” continued—that their relation to the United States remained that of “a ward to his guardian”—and refused to hear their case. The Court’s decision undergirds the legal relationship of Indigenous nations and the United States to this day, and it set a precedent for decades of Indian removal and undeclared war waged in the name of the Great White Father for the announced benefit of his so-called children.

Looking back half a century later, Theodore Roosevelt described Indian removal as one stage of a process that had begun with the Saxon conquest of Britain and swept forward through the “world’s waste spaces.” It had been inevitable (for “this great continent could not have been kept as nothing but a game preserve for squalid savages”) but not a given. In Roosevelt’s view—as in Patriot Front’s now—victory over “red foes … strong and terrible” had proved the superiority of white American manhood. And once the frontier had been pushed all the way to the Pacific, Roosevelt and others moved to extend the civilizing process overseas, where a new generation of American men would have the chance to show themselves worthy of their inheritance—and just in time.

In 1898—amid a widely diagnosed crisis of American manliness brought on by competition with European empires, enervating new forms of industrial work, the arrival of millions of new immigrants, and the increasing authority of women social reformers, among other factors—fatherhood was recast as the nation’s global purpose, and Roosevelt its leading statesman. He had resigned his post as assistant secretary of the Navy to lead the Rough Riders in Cuba and rose to the presidency within three years of his return. “Exactly as each man, while doing first his duty to his wife and the children within his home, must yet, if he hopes to amount to much, strive mightily in the world outside of his home,” Roosevelt explained in 1901, “so our nation, while first of all seeing to its own domestic well-being, must not shrink from playing its part among the great nations without.” In contrast, he described anti-imperialists as “beings whose cult is non-virility.”

This wasn’t just a metaphor. White fatherhood was fashioned into a grim duty through the work of one of Roosevelt’s British friends, Rudyard Kipling, who had grown up in India and England idolizing Mark Twain. In 1892, Kipling married a New Englander, settled in Vermont, and began to remake himself as a paragon of American manhood, only to be emasculated by the press during a family dispute that ultimately sent him scurrying back to England. In 1898, Kipling cheered Roosevelt’s success on San Juan Hill from afar, but he was eager to be more involved. “Now go in and put all your influence into hanging on permanently to the whole Philippines,” Kipling advised his friend. For encouragement, he also sent along a draft of a new poem, titled “The White Man’s Burden.”

Like Roosevelt, Kipling took it for granted that the white man’s burden was in fact the white father’s burden. “Send forth the best ye breed,” Kipling instructed fathers in the poem’s opening lines, written not long after the birth of his own son, John. “Go bind your sons to exile / To serve your captives’ need.” Specifically, he had in mind a civilizing conquest of the “new caught sullen peoples” of the Philippines, “half devil and half child.” This conquest was to be carried out for the good of those conquered: no more hunger, no more disease, “the end for others sought.”

Roosevelt, then governor of New York, passed Kipling’s verses on to the influential senator Henry Cabot Lodge. Lodge handed copies around the Senate, which, on February 6, 1899, a day after the poem’s publication, voted to fight to annex the Philippines to the United States, rather than leave it for Filipinos themselves. In certain districts of the Philippines, seeking “the end for others” would come to mean ordering the killing of all males over 10 years old.

“America is our nation, passed down to us by our fathers, and so long as we live, the enemies of our people will not stand unopposed,” tweeted Patriot Front in the fall of 2017, soon after it was founded by a teenaged Thomas Rousseau, then living with his divorced father in suburban Dallas. According to a 2019 ProPublica report, the group’s members are young men, mostly without wives or girlfriends, who spend a lot of time online and playing video games—“the nerdy boys that sit next to you in high school.” The Anti-Defamation League found that they were responsible for 80 percent of white supremacist propaganda distributed in the United States in 2020. In 2021, the Southern Poverty Law Center documented 42 chapters around the country.

Patriot Front members dress up in the uniform of white fatherhood because they fear that their claim on that role is in doubt. This fear has been passed down from fathers to sons across centuries of American history, along with the conviction that “strong families” of the type that Patriot Front celebrates—white and patriarchal—prove their strength through violence. The result is a war so old that its battledress now looks like casual wear, a war that can never end because its combatants believe it to be their lifeblood. This deep conflation of fatherhood and military conquest is exactly what makes Patriot Front so dangerous, and not only to those they perceive as enemies.

Consider the case of Kipling. When war broke out in Europe in 1914, the poet avidly took up the cause: “For all we have and all are, / For all our children’s fate / Stand up and take the war / The Hun is at the gate!” Seventeen-year-old John Kipling, small, slight, and nearsighted like his father, was eager to stand up and take the war. His father called in a favor with an old friend, who found a place for him as a platoon commander in a volunteer infantry battalion that went to the front, arriving in France around John’s 18th birthday, August 17, 1915. The next month, he and his men saw their first action, a blunt assault on German machine gun lines in northern France. John disappeared in the chaos.

For years Kipling searched for his son. He visited hospitals on the front, tracking down men who had served with John. He enlisted the aid of powerful friends, including the Crown Princess of Sweden, whom he had met when he won the 1907 Nobel Prize for Literature—but to no avail. All the while, Kipling received letters saying he had gotten exactly what he deserved.

In 1917, Kipling stopped looking. He joined the Imperial War Graves Commission, selecting the phrase “Known Unto God” for the headstones of those who had been killed but could not be identified. The next year, he published a poem called “The Children”: “They believed us and perished for it. Our statecraft, our learning / Delivered them bound to the Pit and alive to the burning.”

In America, it’s a tradition as old as the nation itself: one way or another, white fatherhood consumes its children.