Last Dance

At a World War II internment camp, George Igawa entertained thousands of incarcerated Japanese Americans—while teaching a band of novices how to swing

In 2012, I decided to retire from touring as an indie rock musician and enter a graduate program in American Studies at the University of Wyoming. I’d been living in my hometown of Nashville and, having been to Wyoming only once—on a day trip to Yellowstone many years before—I imagined my new home to be a large and empty place. The idea of emptiness appealed to me. Wyoming was a blank page, and I pictured myself reading books and climbing mountains, engaging in a scholarly pursuit of knowledge in a tranquil natural setting.

After settling in Laramie, I realized, of course, that even a place as sparsely populated and expansive as Wyoming is hardly blank and empty. Wherever my boots trod, they fell upon many deep layers of overlapping histories. I immersed myself in my studies, doing archival research and oral history work. I continued to play gigs, and I took every opportunity to embark on outdoor adventures. For three charmed years, I came to know the state well. I marveled at its geology, animals, and plants. I heard old hunting tales, stories from the rez, stories of homesteaders, settlers, and outlaws. Most revelatory were the stories I heard of people who looked like me: that is to say, with origins on the Asian continent.

When one of my professors heard that I was trekking around every weekend, he told me to check out a place called Heart Mountain in the northwestern part of the state. During World War II, he told me, Heart Mountain was home to one of 10 concentration camps established in the United States following the attack on Pearl Harbor. A total of 120,000 Japanese Americans—most of them U.S. citizens—were removed from their homes on the West Coast and held without regard to their constitutional rights. There were no trials, no juries, just an atmosphere of wartime hysteria that followed a history of anti-Asian economic jealousy and prejudice dating back to the 1800s. Heart Mountain had 14,000 prisoners; if it had been a city or a town, it would have been the third largest in the state.

Growing up in Tennessee in the ’90s, I had never heard about Japanese-American incarceration, or Japanese internment, as it’s more frequently called. In fact, I’d never learned any Asian-American history in schools. I wish I had, because as an Asian American (my mom is Vietnamese), I always felt a bit like I was on an island. I often joke that Wyoming, one of the whitest states in America, is where I actually became “Asian American,” but it’s true. Out west, I visited the largely forgotten sites of former Chinatowns and joss houses (another term for Chinese temples). I saw where massacres once took place. I learned the histories of Chinese miners and rail workers and read about the Asian sailors and slaves who had come to this country as early as the 1500s. My travels became the basis of my scholarly work, and my trips to Heart Mountain played perhaps the biggest role of all.

Getting to Heart Mountain is easy enough. It’s between the towns of Cody and Powell, and a simple turn off Highway 14 brings you to the sparse ruins of the camp. Where once stood a square mile of hastily constructed tar-paper barracks, you now find a single original barracks, a replica guard tower, and a few interpretive signs tucked into sprawling fields of farmland. For a while, the farmer who took over the surrounding land grew sunflowers in the summer, a stark, beautiful sight against Heart Mountain itself, which cuts its silhouette into the expansive blue sky.

The grounds also house a small museum that attempts to tell the complicated story of what life was like for Japanese Americans incarcerated during World War II. You learn who the prisoners were and what they did, as well as how they endured harsh weather in so desolate a setting, in quarters surrounded by barbed wire, surveillance spotlights, and guards wielding machine guns. The stories of their endurance still haunt this landscape, and if you listen carefully enough, you just might hear them whispered through the sage. Other stories, however, are more easily discerned, if only you know where to look.

One day, I stumbled across a photograph of the George Igawa Orchestra, a jazz band consisting of a dozen or so Japanese-American guys playing horns, drums, bass, the works. I had gone to a music college, a jazz college at that, but I had never learned of any Asian-American popular musicians. I certainly hadn’t heard of George Igawa. Intrigued, I pored over archives and old government maps, filled notebooks with my research, and began to stitch together the story of this band, even interviewing its last living members—one of whom, vocalist Joy Teraoka, now 97 years old, has become like family to me. It turns out that the George Igawa Orchestra, made up of prisoners at Heart Mountain, was not only the best swing band in Wyoming, it was also the only swing band in Wyoming at that time. The ensemble performed both inside the camp and outside it, at war bond rallies and community events throughout Wyoming. How could I have never heard of this band before?

As a scholar of music and sound, I find that history tends to leave out certain auditory details. We can read the words of the Gettysburg Address, but what were the tone and timbre of Lincoln’s voice on that November day in 1863? How did it sound to a soldier 10 rows back? Did the wind kick up at any point? Did a bird call in the distance? If so, what kind of bird? A musician’s ear, perhaps, is more attuned to the silences in our history books. So when I felt ready to tell the story of George Igawa and his band, I knew that I had to do more than simply write a paper that I could present at an academic conference. I wanted to share it with more people, especially my fellow Wyomingites, many of whom had never learned about the concentration camp in their state. The best way I knew how to do that was through music—and so my folk song “The Best God Damn Band in Wyoming” was born.

Under starlight they danced behind barbed wire

Under the mountain, it meant something to sing

Stuck between two countries in a fire

The best god damn band in Wyoming …

Ten years after my first visit to Heart Mountain, the song has been heard by thousands of people around the world.

While in Wyoming, I started writing other songs about hidden Asian-American histories, and that work has evolved into a hybrid scholarly and musical practice, further developed during my PhD work in American Studies at Brown University and culminating in a dissertation that pushed beyond the typical boundaries of academic writing. The last chapter of that dissertation, in fact, is a vinyl record called 1975, on which “The Best God Damn Band in Wyoming” appears. The album was commercially released through Smithsonian Folkways in 2021. I have also told the story of George Igawa’s band through other media: documentary film, podcasts, and an immersive multimedia concert project called No-No Boy, named for those internees who dared respond no to two questions on the “loyalty questionnaire” demanding their allegiance to the U.S. government.

To get there, though, we must first go back in time.

Our setting is Heart Mountain in the spring of 1944. The war rages on. It’s dusty and cold. There is a lot of shame experienced by those incarcerated in camp, a lot of boredom. Life, for most, has never been grimmer. And yet it goes on. Farmers till the land, teachers teach, students learn, sports are played, music is made—and at the center of all that music-making is George Igawa.

Igawa was born in Los Angeles in 1908. Prior to his arrival at Heart Mountain in 1942, he had established himself as a tenor saxophonist in a Los Angeles swing band called the Sho Tokyans, which played up and down the West Coast and even had a brief residency in Japan. After being forced from his home and detained in Pomona, California, where he awaited news of where he’d be incarcerated, Igawa sought other instrument-carrying detainees and formed a band called the Pomonans. At Heart Mountain, they added several more musicians to their ranks, transforming into the George Igawa Orchestra and rapidly growing in popularity throughout the region. Igawa did an admirable job of transforming a group of novices—including untrained high schoolers, such as Joy Teraoka and trumpet player Yone Fukui—into a formidable big band. Between relocations and work leaves, high personnel turnover routinely shifted the ensemble’s lineups, but by the end of his time in Wyoming, Igawa had delighted dancers with dozens of performances and given many young people what felt like the musical opportunity of a lifetime.

For its first two years there, the band developed a repertoire of popular big band songs, performing often at dances held at the camp. But in 1944, Igawa guided his young musical disciples through an innovative and challenging program of transpacific musical fusion, consisting of swing arrangements of traditional Japanese tunes. This took them into a new musical space, and not just by the standards of the camp—no band in America was exploring this artistic terrain.

As an older nisei (second-gen Japanese American) with a deep cultural connection to both Japan and the issei (first-gen), Igawa made these arrangements not only to do something artistically interesting but also to appeal to those in the older generation who did not attend the dances held at camp. He bolstered his ranks with issei singers and instrumentalists who performed on traditional instruments such as shamisen (akin to a banjo), koto (plucked zither), and shakuhachi (wooden flute). He also added traditional Japanese dancers and incorporated his frequent collaborators, Al Tanaka’s Surf Riders, who had performed popular Hawaiian music during intermissions at most of the Igawa Orchestra’s concerts since the fall of ’42.

This musical revue, which had six performances, mustered all of Igawa’s musical skill and drew on his background performing jazz on the West Coast and from his time touring Japan with the Sho Tokyans. Japanese musicians had been putting their spin on American jazz since the early 20th century, but before this revue, no American popular musician had seriously considered arranging traditional Japanese songs—the music many issei would have connected with—for a swing orchestra. This was not a commercially driven novelty performance, like many of the pop hits released by the Japanese divisions of the Columbia and Victor recording companies in the ’20s and ’30s, nor was it akin to earlier American minstrel performances that took up “oriental” music and subjects for comedy. Igawa wanted to create a show that combined the distinct but overlapping cultural influences of his Japanese-American identity while providing joy and escape for several generations of people locked inside a concentration camp. It is one of the most extraordinary American musical performances that almost no one knows about.

By April 1944, Igawa had secured work leave in Chicago. (After 1942, the U.S. government encouraged Japanese Americans to resettle in the Midwest, a lukewarm attempt to right the wrong of incarcerating so many innocent people.) And so, the George Igawa Orchestra’s last official gig took place at 7:30 p.m. on April 22, 1944, at a sports awards dance held at the Heart Mountain high school gym. The school was in the center of the project, occupying an area of two blocks. It had been completed the previous year to provide education for the 1,500 high school students in the camp, and the gymnasium, to the envy of some Wyomingites, was one of the nicest facilities in the state.

At least 16 musicians would have participated in the performance that evening, and one can only imagine how excited they must have been. I love to think of young Tets Bessho, one of the high school musicians Igawa had shepherded from Pomona to Wyoming, now Heart Mountain’s most talented musician. The young clarinetist and sax player had blossomed in these difficult circumstances, performing at multiple social events each week. I can picture that April evening, a crowd of 400 expected at the high school, and Tets making his way from the barracks in the northeast section of camp, walking the half mile with his sax in one hand and his clarinet in the other, probably missing dinner in the mess hall to set up and soundcheck with the band before the gig.

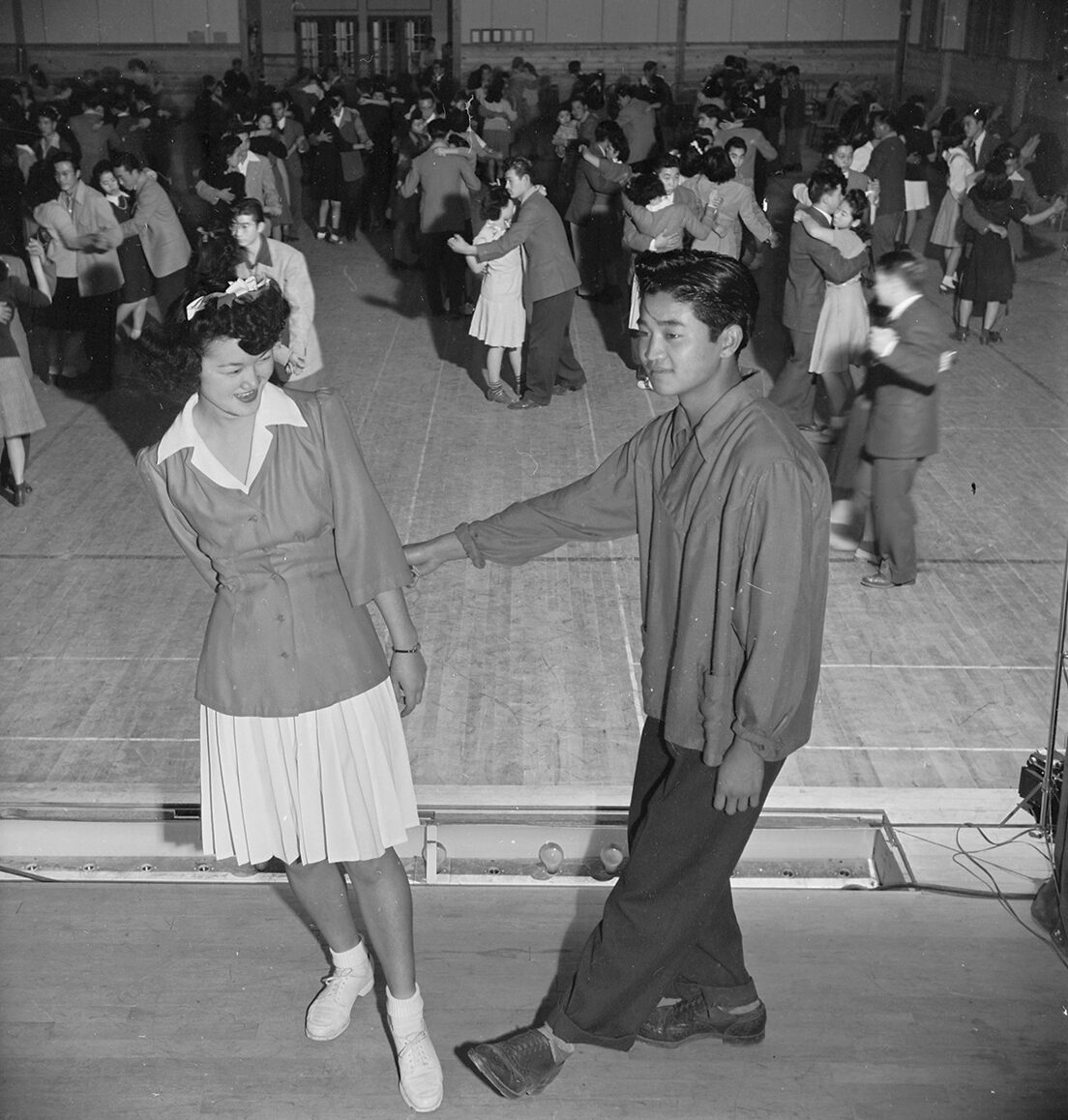

Laverne Kurahara dances the jitterbug with Tubbie Kunimatsu, who sang with Igawa’s band. (Hikaru Iwasaki)

This performance was not an East-meets-West musical revue, but rather a straight-ahead swing music affair, the kind of performance Igawa’s young band members—and the hundreds of teenagers gathered at the high school—adored. Indeed, the big band music of Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, Glenn Miller, and others was hugely popular with the nisei. Teraoka said that hearing the pop hits of the day in camp “was the thrill of a lifetime.” It was common for young folks to hold jam sessions in the recreation or mess halls, where they would play recordings of the day’s most popular songs on a phonograph borrowed from the recreation department. The teenagers would often sprinkle Cream of Wheat on the floor to facilitate sliding and jitterbugging. Like trumpet player Walt Hayami, who blared Gene Krupa on the radio in his family’s cramped quarters, many younger nisei, especially those in Igawa’s dance band, dived deep into swing music.

No full set lists survive from any of the Igawa gigs in camp, but we have a good idea of the band’s repertoire from newspaper clippings, interviews with former members, and the work of musician-historian George Yoshida. From these various sources, I have been able to reconstruct what likely took place on that boisterous and momentous spring evening.

When the George Igawa Orchestra took the stage for the last time, to rapturous applause, the band probably began with its theme song, “Moonlight Serenade,” a down-tempo number whose famous opening strains evoke an ethereal, almost haunting romance. Igawa had deftly altered stock sheet music to replicate Glenn Miller’s standard-bearing arrangement, familiar to the audience from recordings and radios played around camp. Bessho would have brought forth the choice clarinet lines as the dancers took to the floor, easing into the evening with a slow dance.

The band then would have picked up the tempo with a number like “Pennsylvania 6-5000,” and jitterbugging would have ensued, at least among the L.A. kids familiar with the music of the Black and Mexican communities—sweat beads forming, young women spinning out, brave but less coordinated attendees stumbling and losing track of their steps, ace dancers enjoying athletic, physical catharsis and impressing those on the sidelines. During the fast numbers, the strictly slow-dance crowd would join the wallflowers on the edges of the gymnasium, perhaps munching on meager refreshments and providing a bed of chatter underneath the band’s performance. Feet tapping, shoes sliding, an out-of-tune note or missed entrance here or there, laughter, smiles creasing faces, sexual anxiety, off-color comments, zoot-suited posturing: this was the vibe, as the grim reality of concentration camp life remained well outside the gymnasium’s double doors. After an hour or so, the band finished the first set and left the stage for intermission.

During the intermission, while sports awards were handed out to the camp’s best basketball teams and outstanding individual players, some of the band members probably grabbed a cigarette and some gossip outside. The young ballers accepted their awards to the applause of the crowd, and community activities supervisor Marlin T. Kurtz would have closed the intermission with some uplifting words about the merits of athletic pursuit, or some other such boilerplate, before reintroducing Igawa and his band. Once again, the musicians took their places behind their stands and a few RCA microphones, and the music resumed.

As the evening wore on, feet grew sore. Four hundred different energies mingled together and synced up to the rhythm of drummer Jimmie Akiya as the big band echoed through the cavernous auditorium. Favorites such as “In the Mood” and “At Last” were likely performed, providing opportunities for frivolity, romance, and connection. Standout trumpeter Yone Fukui took a few solos. Bessho switched between sax and clarinet as needed. Igawa improvised a bit over the sounds of his musical wards. The music, though nowhere near perfect, did its job and carried the night.

And then it was over. The attendees applauded. Igawa smiled his picture-perfect smile and took one last bow. The crowd lingered and then filed out into the cool spring night. The dance was done. That was it.

The voices gradually dissipated. The soft ripping of tape and the crinkling of crepe paper could be heard as dance chairman Mas Morioka and members of the athletic department tore down the decorative streamers and put away the refreshment tables. Onstage, the trumpet and trombone players blew swift bursts of air through slightly numb lips to remove spit from their horns. Bessho took apart his sax and clarinet, packed them away, and latched his cases shut. The custom “GI” music stands that camp carpenters had made were carried off the stage.

The temperature outside had dipped down into the 40s by the time the band left the gym. Bessho shuffled along the dirt roads back toward Block 24. What would he do next? Was he thinking about the fact that his mentor, George Igawa, the musical engine of the camp, was slated to leave him and his bandmates not long after? Did Bessho feel that typical mix of gratitude and betrayal so many musicians have experienced when a band ends? There would be no more daily rehearsals. Igawa would spend the next weeks making arrangements for his relocation to Chicago and for his wife, Kimiko, to eventually join him there.

High from the gig, Bessho probably didn’t reckon with any of these anxieties. It’s doubtful he registered the bittersweetness of the moment. He probably didn’t even go back to the apartment where his parents were likely sleeping. No, the way I imagine things, the members of the band would have kept the good times going, roaming Heart Mountain’s dirt roads in the moonlight, swigging some contraband whiskey that’d been snuck in through the barbed wire. Jimmie, Yone, Tets, and the crew stirring things up, squeezing as much life from the desolate northern Wyoming landscape as they could, dancing in the glow of the searchlights.

For the next nine months, dances at the camp were accompanied by recordings played through tinny PA systems, a thin substitute for Igawa’s irreplaceable blend of horns, piano, live drums, and thumping bass. Before his departure, Igawa had handed over leadership of the band to Bessho. The young clarinetist made a bold attempt to reform the big band, but the task proved too tall. Small groups entertained at socials, but the big band dances were done, and gone were the improvisations, the mistakes, the thrilling dynamics and tempo pushes. In their place? Records that always sounded the same, spinning around and around on a phonograph.

Igawa’s departure left a gaping hole in the sonic landscape emanating from below Heart Mountain, and one of the greatest musical acts in Wyoming history would disappear from the record—except for one black-and-white photo in a small museum.

Heart Mountain looms behind F Street, the main thoroughfare cutting through the camp. (Tom Parker)

In the years after finishing my initial research on the George Igawa Orchestra, I started the No-No Boy project, an immersive multimedia concert work blending original folk songs, storytelling, and archival images, all in the service of illuminating hidden American histories. When I perform live, I project curated archival images that sync up with folk songs I write about those stories. Many of these songs are inspired by my own family’s history during the Vietnam War, the experiences of Asian Americans who lived through the Chinese Exclusion Act and Japanese-American incarceration, and our present-day refugee crises. My goal is to use multimedia art to reach large audiences, to connect with a public increasingly skeptical of “experts” and “facts.” I think of my performances primarily as ways to engage diverse audiences with difficult conversations through deceptively simple songs. Whether performing at Lincoln Center or for rural high school kids in Oregon, I approach each gig the same, using music and moving images to invite audiences to sit with the mess of history. Additionally, by turning my research into art, I can regularly revisit and revise my work. A book represents a kind of finality, whereas each of my concerts is a chance to defend and reconsider what I’ve learned.

The story of George Igawa and his Asian-American musicians remains at the heart of my project. In an era of scholarship obsessed with the traumas of American history, I’ve found it important to provide a fuller picture of dark times, to bring a higher fidelity to what has typically been a mono record. This I can do by celebrating the joy cultivated amid tragedy and injustice.

The last time I hiked up Heart Mountain and looked out at where the camp used to be, there was—as with many vistas in Wyoming—a whole lot of nothing below. But I closed my eyes and listened deeply. I thought back over the archives I’d searched and the oral histories I’d collected, summoned forth in my mind the barracks and the barbed wire, tried to feel the exhilaration and the pain and the erasure of the past. I heard thousands of faint overlapping histories. I heard George Igawa saying “Thank you” for the last time. I heard the strains of “Moonlight Serenade” swelling in the distance. No place is empty.