Inside Comedy: The Soul, Wit, and Bite of Comedy and Comedians of the Last Five Decades by David Steinberg; Knopf, 352 pp., $30

There’s a Mitch Hedberg-esque joke to be made that would go something like, “Why is there an ‘About the Author’ section in an autobiography? The whole book is an About the Author section!” But such is the case with David Steinberg’s Inside Comedy: The Soul, Wit, And Bite of Comedy and Comedians in the Last Five Decades, a whole book written in the tone of boldfaced aggrandizement usually reserved for dust jackets.

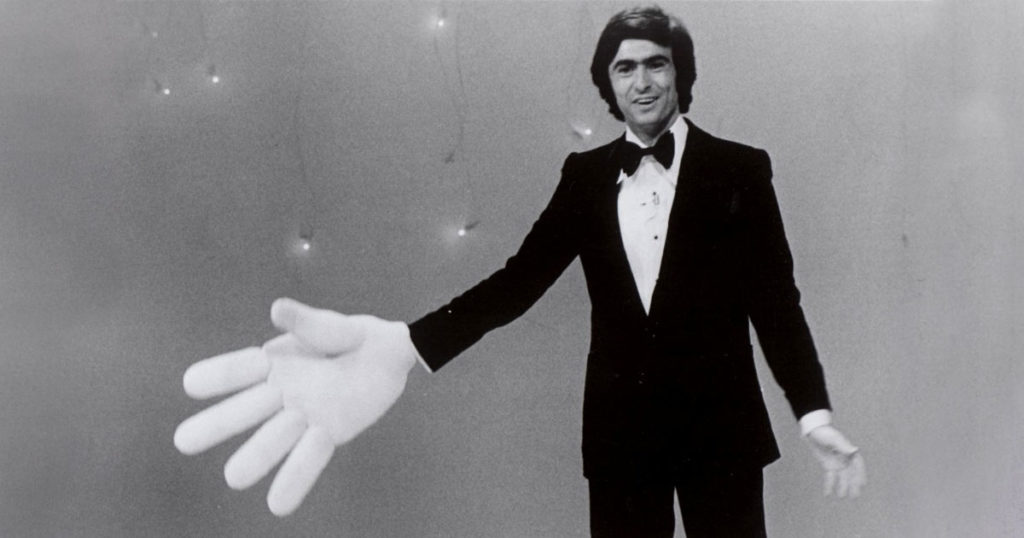

Steinberg’s career has been charmed. Forrest Gumping his way through comedy and showbiz for 60 years, he did his first stand-up alongside Richard Pryor and George Carlin, joined an early Second City class, and performed on The Tonight Show over 100 times, eventually guest hosting. Steinberg went on to direct episodes of Mad About You, Golden Girls, Seinfeld, and Curb Your Enthusiasm.

He’s responsible for such great lines as “God, whom I’m sure you will remember from last week’s sermon …” Also storied quips, like this one in response to Bea Arthur wondering why people often take an instant dislike to her: “It just saves time.” Steinberg was great for lots of reasons: He didn’t change his last name—to make it sound less Jewish, one of his jokes went, he’d have to shorten his last name to “St.” He told stories and teased out ideas while many comedians were still relying on the setup-punchline jokes of the Catskills variety. He talked about real life: growing up lower class and Jewish, and was early to set as the target of his jokes racism instead of just race. His fame soared. One rumor had it the song “You’re So Vain” is about him, as he lived below and performed with Carly Simon. His comedy and onstage persona has for 50 years been smart, likable and often poignant.

Steinberg lets none of this likability, wisdom, or humility slip into the book. It’s a dazzlingly brave comedic choice. If we read Inside Comedy as a send up of the lack of self-awareness so often rewarded in show business, as a parody of the celebrity memoir in which the author conflates proximity with importance, as an end-of-life cash grab, then Steinberg’s book is an astounding success.

“There are things I’m too modest to tell you,” Steinberg writes in his book’s opening chapter, and then spends the next 300 pages telling us those things. (Drink every time you hear a legend is his “dear friend” or “good friend.”) Things he’s too humble to say include his assertion that he “may be the only comedian to have made Elie Wiesel laugh.” That he was admired by S. J. Perelman, Harold Pinter, and Philip Roth. Was “virtually adopted” by Hillcrest Country Club old-timers Groucho Marx, Jack Benny, and George Burns. That musicians like Dionne Warwick, Frankie Valli, and Miles Davis “were fans of mine because they identified with what I was doing.” He spends paragraphs explaining a Canadian award, so that we may understand how big a deal it was that he received it. “I’m the Martin Scorsese of Canada,” he mentions as an aside about tax law. It’s pitch perfect.

Of course, we want to hear all about Steinberg’s accomplishments. To see them, be with Steinberg as they happen. “And I held court every morning at the coffee shop and after a while you just couldn’t get into the place.” Neither, in any real sense, can the reader. The book is tantalizing but frustrating, much like a career in showbiz. Steinberg’s heavy-handed yet opaque narration evokes the exclusivity of his fabulous life, just as it underscores the unknowability of what’s behind the clown’s makeup.

In what can only be taken as a wink at the subjectivity of showbiz history or memory, the comedians interviewed in the book, purported to represent the most important of the past five decades, just so happen to be the ones who appeared on Steinberg’s Showtime interview series, Inside Comedy. Some stories are great. Sarah Silverman explains how, as a 14-year-old living in New Hampshire, she had a David Hockney poster on her wall simply because Steve Martin once mentioned liking him. But the book largely consists of transcripts of these interviews, which are already available to stream online, shot through with Steinberg’s interjections.

Thus Inside Comedy is neither a comprehensive account of the comedians of the middle of the 20th century, as the title promises, nor a closely observed personal account of Steinberg’s life. We watch as Steinberg flails, killing no birds with two stones. It’s brilliant narrative slapstick. Steinberg seems to say with every page, Why would you assume, nay demand, I write memoir AND history?

As Mitch Hedberg joked,

When you’re in Hollywood and you’re a comedian, everybody wants you to do other things besides comedy. They say “All right you’re a stand-up comedian, can you act? Can you write? Write us a script.” They want me to do things that’s related to comedy but not comedy. That’s not fair. It’s as though if I was a cook, and I worked my ass off to become a good cook, and they said “All right you’re a cook … can you farm?”

The crazy thing is, Steinberg actually did make those leaps successfully—until it came to this book.

Like an unpolished joke, Inside Comedy is not perfectly chaotic. Steinberg occasionally breaks character long enough to relate some enjoyable stories: how he ended up the best man at Mobster Joey Gallo’s wedding; how a former valet attendant named Larry Charles, whom Steinberg once helped break into the industry, called him years later to ask that he work on a new NBC show called Seinfeld. He also offers brief glimpses into the ache of being once-famous: Steinberg seeking out older and older flight attendants in the hope of being recognized. He teases us with stories and insight that could have elevated Inside Comedy beyond the solipsistic. But in the end, the book mostly feels like a comic telling readers how he killed: how he hung out with legends like Groucho and Johnny Carson and formed great friendships. When, as in life, people also want to hear about the times you bombed.

Maybe everything really was that charmed and simple. Or maybe this book is Steinberg’s act of graciousness: he truly has had a remarkable career. Done and made great things. That he made a book so bad is refreshing. It gives hope to those of us envious of the life he’s lived.

If only Steinberg and his publisher were in on the joke.