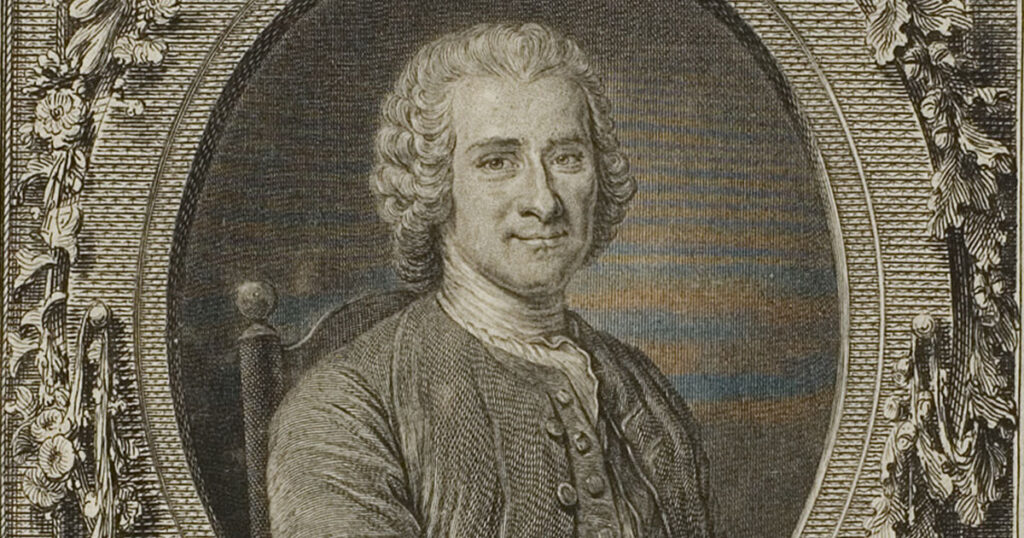

When my children were little, I found myself immersed in Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Emile. Part treatise on education and part novel, Emile calls out the artificiality of social expectations, which can lead to suffering, anxiety, and physical ailments. Rousseau advocates instead for a system of education that can free human beings from the chains of public opinion while fostering virtuous interactions with others. For Rousseau, the arbitrary rules and conventions imposed by society and well-meaning parents only stifle a child’s capacity to learn.

Sometimes, after days tending to my children, I would read passages aloud to my husband and we’d laugh over the impracticality of Rousseau’s suggestions: exposing children to cold weather or setting them loose in the woods so they would get lost and have to find their way home. Rousseau, moreover, wasn’t a model parent. He fathered five children and took them all to a foundling home. We do not conclusively know what happened to them, but given the conditions of foundling homes in 18th-century Europe, Rousseau almost certainly doomed his offspring to a nasty, brutish, and short life. Apparently, like so many of us, he was better at giving advice than doing the work of parenting.

Although my children are grown now, I still find myself thinking about Rousseau’s approach to education. As a social philosopher, I see his project as visionary. Indeed, Emile’s contributions to discussions of human relations, justice, and politics remain relevant. Rousseau understood that people don’t appear fully formed, ready to take their place in society as responsible and contributing citizens. Emile offers his detailed description of raising a child according to nature, for the good of the child and the community.

Rousseau’s wonderfully rich text—beginning before the birth of Emile and concluding when, as a young adult, he meets his perfect mate—teaches that human beings need to learn how to be social. The past few years have punctuated the importance of Rousseau’s lesson. The lockdowns brought about by Covid provided a sort of reset: a long period of isolation followed by a gradual reintroduction to social life. But the modern world is too infected with all the things Rousseau disdained: the curated images of self constantly on display in social media and the celebration of uncivil or cruel behavior—especially on “reality” shows that distort what their name promises. I doubt Rousseau would find our forms of social existence compelling. Contemporary human beings worry too much about the opinions of others and too little about the cultivation of empathy.

Login to view the full article

Need to register?

Already a subscriber through The American Scholar?

Are you a Phi Beta Kappa sustaining member?

Register here

Want to subscribe?

Print subscribers get access to our entire website Subscribe here

You can also just subscribe to our website for $9.99. Subscribe here

true