The Caribbean experience has, since the “discovery” of the West Indies in the 15th century, been marked by exile, displacement, comings and goings, and the creation of diaspora everywhere from Canada to the United Kingdom to South Africa, where West Indian merchant marine men settled at the turn of the 20th century and the height of the Anglo-Boer war. Our literature is filled with stories that recount and lament what happens when one goes to seek fortune and family elsewhere. We’ve always, necessarily, had an elastic sense of both home and time, cultivating connections to our beloveds (or, as in the case of Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy, eschewing these ties) while adjusting to the new places we’ve adopted.

My debut novel, The Star Side of Bird Hill, is a coming-of-age story focused on a family of women—two girls reeling in the face of their troubled mother’s unraveling and their abrupt landing with their grandmother in Barbados. I wrote this coming-to-the-Caribbean story in an effort to better understand an experience that imprinted itself upon me in childhood, that of leaving home in America and visiting my parents’ islands in the Caribbean, which I also claimed as home.

Other books, of course, explore these themes: exile, homesickness, displacement, being a stranger in a land that feels both foreign and familiar. I found it incredibly difficult to cull this list to ten titles, so I selected books published in the last ten years (Caribbeanists will note the absence of a few important classics, including Samuel Selvon’s novel The Lonely Londoners and George Lamming’s essay collection The Pleasures of Exile). In curating this list, I chose titles both within and outside the Caribbean literary tradition and considered not just physical but also psychic exile, bearing in mind this quote from “Who’s Listening,” M. Nourbese Philip’s essay in Frontiers: Essays and Writings on Racism and Culture:

“Audience is a complex and difficult issue for any artist, particularly in today’s world where any sense of continuity and community seems so difficult to develop. It becomes even more complex for the artist in exile—working in a country not her own, developing an audience among people who are essentially strangers to all the traditions and continuities that helped produce her. Scourges such as racism and sexism can also create a profound sense of alienation, resulting in what can best be described as psychic exile, even among those artists who are not in physical exile.”

Americanah, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

Adichie’s third book bursts at the seams with stories about whether and how true love might be found and sustained, how Africans become black and negotiate racism in America, and whether Nigerians who’ve been living in the United States, the Americanahs to whom the title refers, can ever go home again.

A Thread of Sky, Deanna Fei

Deanna Fei’s A Thread of Sky follows three sisters on a tour of China with their mother, aunt, and grandmother in the wake of their father’s death. Fei richly illustrates the conflicts between sisters and generations as well as how the women have fallen short of the lives they imagined for themselves and each other. Each generation has a different relationship to China, giving the novel ample room to explore the costs and rewards of immigration and exile.

Oh Gad!, Joanne C. Hillhouse

Joanne Hillhouse’s Oh Gad! tells the story of Nikki Baltimore, who decides to leave a comfortable but unhappy life in New York City to reconnect with her family in Antigua after her mother’s death. She finds herself stepping onto landmines of old hurt as she tries to make a life among her maternal siblings in Antigua, which she knows from childhood summers there, but has never before called home.

A Brief History of Seven Killings, Marlon James

Winner of the 2015 Man Booker Prize, Marlon James distinguishes himself with this novel’s epic scope, panoply of characters, innovative narrative style, and athletic prose. What I found most compelling in A Brief History for the purposes of this list are the characters whose lives we witness in both the Caribbean and the United States–a gay gangster, Weeper, who leaves Jamaica to expand the drug business Stateside, and a woman who flees Jamaica and tries to assume a non-descript Caribbean-American womanhood as a nurse in the Bronx. Both characters beg the question of what Caribbean people must give up and take on in order to create new lives outside the class structure and social conventions they’ve left behind at home.

I’ll Never Write My Memoirs, Grace Jones

Grace Jones details her spectacular life in the limelight, including modeling, acting, music, and unclassifiable ribaldry, in this aptly titled memoir. The most interesting sections of the book, however, are the chapters where Jones describes her early childhood in Jamaica before she leaves for the States, her rebellion against the conservative culture of her family and community, and how returning to her artistic and cultural roots feeds her music.

Lucy, Jamaica Kincaid

Following the publication of her debut novel, Annie John, which ends with the title character leaving her home island of Antigua for England, Kincaid published Lucy, a sequel of sorts. It’s the tale of Lucy, an au pair for a wealthy New York City family, who is fiercely committed to herself and her independence. Lucy is remarkable in that it questions not just the power and racial dynamics inherent in intimate labor, but also the model of Caribbean women’s devotion to their families in the form of expected frequent contact and financial support.

The Absolutely True Story of a Part-Time Indian, Sherman Alexie with Ellen Forney, illustrator

Sherman Alexie’s first young adult novel, which won the National Book Award, follows the teenaged Arnold Spirit Jr., a budding cartoonist who traverses the chasms of history and personal experience when he leaves the Spokane Indian Reservation for a predominantly white public school off the rez.

Anna In-Between, Elizabeth Nunez

As the title suggests, this novel is the story of Anna, a book editor caught between the life she’s built for herself in New York City and her parents’ lives in the Caribbean. A trip home reveals that her mother has cancer, and prompts a consideration of the turns long-term love must take.

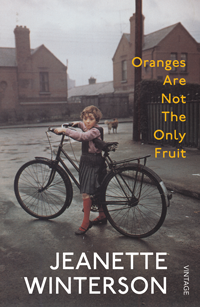

Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal and Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit , Jeanette Winterson

These twin titles cover some of the same ground of trauma, same-sex desire, and beauty. Jeanette Winterson skyrocketed into the literary stratosphere when her debut novel, Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit, was published in 1985. Nearly 30 years later, her memoir, Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal, examines the true story of Winterson’s profoundly unhappy childhood with her adoptive parents. Both books deal deftly with the question of emotional and physical exile from one’s family of origin.