Twice, publishers have approached me to suggest I write a memoir or an autobiography, and both times I instantly recoiled from the prospect. I can’t say quite why I did, perhaps because of the implication that my life was over when to me it seemed so intensely in progress. But just recently a friend suggested a title, The Unfinished Education of Jack Miles, that opened the closed door just a crack. It was the word unfinished that loosened things up, suggesting that whatever had been learned, there was more still to be learned. So perhaps now, homebound amid a pandemic, I could allow myself to tell a few stories about lessons learned long ago.

A first story. The scene is Ireland in the mid-19th century. Because of English colonialism, the rural population has been forced off all the good agricultural land and into the Irish badlands, where little can be cultivated but potatoes. And then something terrible happens. A deadly disease, the potato blight, strikes the island, and famine results—severe, ghastly famine. Potato blight is first identified in County Monaghan, an impoverished chunk in the center of the island, and before the blight is finally contained, 30 percent of Monaghan’s population will die. Now, Owen and Mary Gunn, owners of the farm where the blight is first identified, happen to be my great-great-grandparents. Their daughter Bridget marries a Monaghan man named James Campbell. James and Bridget have a daughter, Catherine Campbell, my grandmother. Catherine emigrates to England to work as a domestic servant in the household of the royal physician. There in England, she meets and marries a laborer named Michael Murphy. Catherine and Michael, Kate and Mike, immigrate to Chicago, where Kate finds work as a cleaning lady and Mike drives a streetcar for the public transit system until he is laid off in the Great Depression. Kate and Mike have a daughter, Mary Murphy, born in 1919, who marries a man named John Miles. John and Mary Miles have a son, whom they name John Miles Jr. after his father but to avoid confusion call by the nickname Jack. John and Mary do not attend college: they can’t afford it. They can’t afford to send me to college either.

This back story, which I know in as much detail as I do thanks to the work of my younger sister Mary Anne, drives home for me a lesson that I have learned in other ways as well—namely, that we never know enough to despair. If three of every 10 people you knew were dead of starvation and others were starving before your eyes, you might well think that it was only reasonable to give up all hope. But it wouldn’t be reasonable. James Campbell was four years old when the Great Hunger began, but he did not die of it. I myself am part of what he did not know would happen.

I am a supporter of MAID, medical assistance in dying, yet I do not believe that despair is reasonable even when death is inevitable, even at the very moment when a mortally ill person ingests the licensed, lethal prescription. I used to think that way, but I don’t anymore. It is not bravery alone that engenders hope. For me, it is also and primarily honesty about how little we know. If we do not yet know what life is even in material terms (because we do not yet know, fully and finally, what matter is), then how can we know what the deprivation of life is? It cannot be said too often: we do not know what we do not know. And where there is such uncertainty, there cannot be despair. Despair requires a certainty that we just never possess. So what matters to me? Hope! Hope matters, invincible hope. A first lesson.

The Great Hunger, depicted here in The Life and Times of Queen Victoria, brought the Campbells—the author’s maternal forebears—to America. (Historical Images Archives/Alamy)

A second story, in three scenes. The first scene is Rome. I am a Catholic seminarian, a young Jesuit, studying philosophy at the Pontifical Gregorian University. After my first year there, in the summer of 1965, I spend five weeks in Germany learning the German language, living with a German family, and falling in love with everything German. One day, I come home from school at an unexpected hour and sense a kind of tension when I enter the apartment. My somewhat elderly host couple is listening to the recording of an impassioned speech delivered in a cemetery where are buried German prisoners-of-war killed by the Americans after Germany surrendered at the end of World War II. Vengeance murders, in other words. Vengeance murders, by Americans of my father’s generation. Awkwardly, my hosts beckon me to take a seat, and when the speech ends, an interesting conversation ensues.

When my course of German language study is concluded, I visit Munich, a truly beautiful city, something close to the capital city of German art, literature, and music. But while there, I take an excursion to a small town some few miles away named Dachau, the site of a death camp where in the 1940s the then-government of Germany slaughtered hundreds of thousands of Jews and others and incinerated their corpses in giant ovens. Back in Rome, a great gathering of Catholic bishops is about to pass a resolution entitled, in Latin, Nostra aetate (“In our time”), by which the Church—appalled, finally, by the slaughter of millions of Jews in the Nazi death camps—will renounce and decry its centuries of ruthless anti-Semitism.

The first scene, Rome; the second, Munich. The third scene in this second story is Jerusalem. I am there for the same reason that I was in Germany during the previous summer. My Jesuit superiors have decided that I should train to become a professor of Old Testament. Much biblical scholarship is available only in German. But, of course, the languages of the Bible itself are Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. I already know Greek, but I am in Israel to master Hebrew, and then to return to the United States—to Harvard, as it turns out—for doctoral studies. There in Israel, like any foreign student at the Hebrew University, I am eager to fit in, to make friends. Though the Israelis never forget that I am American, they can never remember that I am Christian. They treat me as just another American Jew on his junior year abroad, and for my part I begin to feel Jewishly proud of the rebirth of our Jewish national life here in Israel after a 2,000-year interruption, all the while privately happy that the Catholic Church seems tacitly to welcome this development.

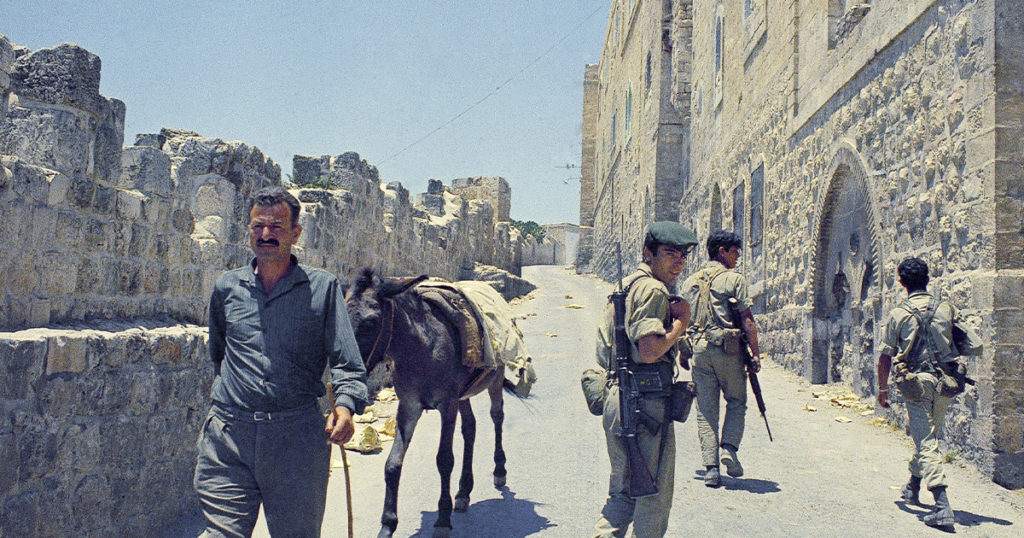

No surprise, then, that when in June 1967 a coalition of Arab states prepares to attack Israel, I join in patriotically as we students put duct tape on dorm windows to prevent their shattering in a bomb blast. I am in Haifa when the air-raid siren goes off, and I take refuge in a designated bomb shelter—the underground garage beneath a car rental agency. Late on the sixth day of the war, when word comes over the radio that the Jews have won and I hear Moshe Dayan, the Jewish commander-in-chief, praying at the Western Wall of the ancient Second Temple, praying in Hebrew a prayer that by now I know by heart, I choke up and my eyes fill with tears. I am that intensely, passionately identified with the Jewish cause. Yet just a day later, I leave the country by ship. I do not want to take part in the victory celebration. I’m just not up to it.

Why? Here I must provide a bit of background. As late as the 1966–67 academic year, the Old City of Jerusalem and all of what is oddly called the West Bank—that is, Palestine west of the Jordan River—is still legally a part of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. As a Christian residing in the State of Israel, I am permitted to and do cross into Jordan at Christmas to visit the Old City of Jerusalem. During this visit, I reside in a Catholic boarding school where I meet young Palestinian Christians my own age who cannot fathom why in this terrible conflict the Christians of America are not standing up for their fellow Christians the way the Jews of America are standing up for their fellow Jews. The church in Jerusalem is, after all, the mother church of all Christendom. With a mix of anger and grief, they challenge me. Why have we American Christians so abandoned our suffering Palestinian brethren? They choke out moving, even heartbreaking stories about how the Jews have robbed them and killed or abused members of their families. What have I to say for myself and my country? At the time, I can only listen. And then something else happens.

Several days after Christmas 1966, with the heaviest influx of tourists now departed, I do some private exploring, hiking my way around the east side of the massive walls that enclose the Old City, and I end up caught in a torrential downpour. Jerusalem gets more rain in an average winter than London does, and in December the rain is icy cold. Heading for home, drenched to the skin and shivering, I have to pass through a city gate guarded by a Jordanian sentry. But I am in luck. This soldier takes one look at me and beckons me into his little guardhouse, an enclosed room built into a recess in the Old City’s formidable wall. He has a tiny stove there, with water boiling for tea. He gestures for me to take off my sopping raincoat. He gives me a little towel to dry my face. I sit down on a straight chair opposite him, and he gives me a glass of hot sweet Arab tea. I do not know this man’s name. He does not speak a word of English. I speak barely a word of Arabic. But something transpires between us, some understanding, something quite real, quite deep, and moving. When I eventually rise to leave, he gestures that I should wait just a moment. And he fishes out a little snapshot of himself in his uniform. No name on the back. No telephone number. No favor even implicitly requested. Just a simple token of friendship, the memento of a fleeting moment of human warmth.

And so it happens that on the first morning after the end of the Six Days War, as ecstatic Jewish victory celebrations break out all over the country, all I can think is that my friend, my rescuer, is dead. How could he, an Arab sentry guarding Jordanian territory against the Jewish invasion, possibly have survived? That’s what I’m asking myself, and, of course, I have no way of checking my intuition. All the same, a feeling in the pit of my stomach makes it impossible for me to take part in the celebrations. I am glad the Jews have won and Israel is safe, but as soon as the Port of Haifa reopens, I board ship and sail for Naples.

About 40 years later, at a time when I am serving as senior adviser to the CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, a letter reaches me from Yale University. An Israeli graduate student in philosophy, a veteran of the Israeli Defense Forces, has read my book God: A Biography in Hebrew translation and wants to start a conversation. This conversation continues for years, and my correspondent, Omri Boehm, now a professor of philosophy at the New School for Social Research in New York, has published a book offering his radical vision of an Israeli future in which all of that country’s actual inhabitants, Arabs no less than Jews, will enjoy full and equal human rights.

What do I take away from this set of highly charged experiences, mostly from my mid-20s, 50 years ago? What I take away is that, yes, it is right to seek justice, and it is essential to seek to right old wrongs and heal old wounds, but justice blindly pursued can so easily commit new crimes and open new wounds. America did so in Germany, notwithstanding the Marshall Plan and other acts of generosity. Israel has done so in Palestine. Justice is commonly portrayed as a blindfolded goddess holding scales in her right hand. The scales represent the facts. The blindfold represents her lack of favoritism. I understand and respect the metaphors and the personification in play, but their application is limited. Wisdom should always, always, be watchful, and when we feel we are most in the right, then is when we should look just a little further to see whether and how we may be about to cause pain, humiliation, and even lasting harm. A second lesson.

Protesters take over Harvard’s University Hall in April 1969. The author was a student there at the time, volunteering with Harvard Big Brothers. (Harvard University Archives)

A third story. The scene this time is Harvard University, 1968 through 1970. While I am there, antiwar student radicals occupy the hallowed University Hall, and the Cambridge police expel them in a bloody nighttime raid that leaves the entire campus in an uproar. Meanwhile, the Civil Rights Act has passed, officially ending segregation, but violent riots have followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. And, not to be omitted, the sexual revolution of the 1960s is fully underway.

On registration day, I am invited, like the other registrants, to volunteer for one or more of Harvard’s many public-spirited clubs and social programs. But I am a 25-year-old Jesuit, just back from Israel and still determined to keep my vow of celibacy. I do not want to volunteer for anything that would put me in the company of attractive young women and tempt me to break my vow. So, what do I do?

I volunteer to take part in the Harvard Big Brothers program. This program pairs Harvard students—especially freshmen, as I will learn—with fatherless Black boys living in a huge housing project on Columbia Point, a peninsula jutting into the Atlantic slightly south of downtown Boston.

Consider now: a young Catholic cleric decides that he wants to work with, uh, little boys, little Black boys … In 2021, this might be about the most suspect, least innocent thing for a Catholic cleric to volunteer for, but back then it was regarded as innocent, and innocent it turned out to be. I was paired up with a fourth-grader named David Farrow, and we went on some kind of an outing every weekend from spring 1968 to spring 1970. Most of the boys whose mothers enrolled them in the Big Brothers program were problem boys. David’s problem was that he was always getting into fights at school. He was short and picked on for that reason. But he was also tough, so if you messed with him, he messed with you. And he had scars to show for it, including a nasty jagged line across his upper lip, plus two front teeth that had been halfway knocked out, so that when he smiled, it was as if he had four pointed incisors. Result: this was one little boy who just didn’t smile much at all. But David was plenty spirited in his own way. Once, when I went to pick him up, he boasted, “We won yesterday, and I hit nine home runs.” I said, “Hey, that’s great, David,” while thinking to myself, Nine home runs? Really? But then I went to one of his games, and the kid was a phenomenon. Every time up, the crack of the bat and then outtathepark. So, I was glad that I had kept my earlier skepticism to myself. And after a while, David’s mother, Mamie, told me that he was no longer fighting in school.

Among many revealing moments over two full years of weekly visits, let me single out just one that taught me something especially important. It was a gray afternoon in April or May. I now had a car, and so I decided to take David and his four siblings out for fried clams at a clam shack on the Atlantic end of the South Boston peninsula, immediately north of Columbia Point. It was raining when we set out. It was absolutely pouring when halfway to the end of the peninsula, my damn car broke down. I told the kids to wait in the car while I walked to where I could get some help, but they begged me not to leave them: they were terrified to be left there alone. Why? I wondered. The rain was coming down in sheets. The streets were empty. The car was safe and dry, wasn’t it? Why so fearful? Well, South Boston—also known as Southie and now, I gather, quite gentrified—was back then a working-class Irish neighborhood just like the raggedy one where I had grown up back in Chicago. These Black kids from Columbia Point were terrified, just terrified, of the white people of South Boston.

In Austin, my old Chicago neighborhood, we were afraid of Black people. The 1940s and 1950s were peak decades in what is sometimes called the Great Migration—namely, of Black people fleeing vicious racism and inescapable poverty in the South and moving to the industrial cities of the North. Existing Black neighborhoods in Chicago became hugely overcrowded in the 1950s, and as they overflowed into adjacent poorer white neighborhoods like mine, violence broke out. My mother was mugged or had her purse snatched several times by Black boys, teenagers or even younger. Black burglars twice struck my brother-in-law’s camera shop, before Black marauders in balaclava masks held him up at gunpoint and cleaned out his shop in broad daylight, stealing his whole stock and forcing him out of business. As a result of these episodes and others, when I first ventured into the Columbia Point housing project, I was afraid that I myself might be mugged or robbed or worse. Nothing like that ever happened, but, believe it or not, it had never once occurred to me that Black people in Columbia Point might be similarly afraid of people who looked like me. But they were, and this came home to me on that rainy day when I left five frightened little Black kids in my locked car. I got the car started soon enough, we all had our fried clams and French fries quite happily, but I drove home full of very tangled thoughts.

After I completed my doctorate, I stayed loosely in touch for a few years with Mamie Farrow, David’s mother, and with David himself. David made it safely through high school and then joined the Marines. At my last attempt to contact him, he was a private down the road at the El Toro base, back when it was still an actual base. I discovered, though, that when you call a Marine base and ask to be connected with a mere private, it ain’t like calling a hotel and asking to be connected to a guest. I got quite the runaround, though after several tries I did almost reach him. Somebody deep in the interior of the base answered the phone, and said, “Farrow? Yeah, he’s around here.” I heard a shout, “Farrow!” and then, “Sorry, Farrow’s out on patrol.” That near miss was my last contact.

Saint Paul in the First Letter to the Corinthians speaks of three great virtues—faith, hope, and love—but, he insists, “the greatest of these is love.” The three vices to which these virtues are opposed would seem to be doubt, the opposite of faith; despair, the opposite of hope; and hatred, the opposite of love. But behind hatred, even ostensibly livid hatred, what you find so often is buried fear. Once we face down our fears, we discover at least sometimes that those we feared were fearful of us. And as the fear subsides on either side, it is—at least sometimes—as if the love that was always there, lying dormant, waiting for its chance, wakes up and starts to sing. A third lesson—among many by then already past but with more, many more, still to come and still coming.