When I moved to New York City in 1980 at the age of 22, I almost never went near 125th Street, the unofficial boundary of Harlem, even though I lived only two blocks away in Morningside Heights, across the street from Riverside Church. Harlem, of course, was the beating heart of Black New York: the Harlem Renaissance, the Schomburg Library, the Apollo Theater, Sylvia’s Restaurant. It was also, less than two decades after the scarring riots of the 1960s, a place where white people just didn’t go. I’d heard the stories—junkies, drugs, guns, violence—and internalized the warnings. Little could I have imagined that by my late 20s I would find myself a fixture on Harlem’s main thoroughfare, one block east of the Apollo, playing harmonica with a Mississippi-born bluesman named Mr. Satan, or that we would break into the national market with the release of our debut album, Harlem Blues. The whole experience demolished the way I’d been programmed to think about Harlem, to put it mildly.

It began one August evening in 1981 when I heard music filtering through my 18th-floor window, along with a warm breeze off the Hudson River. The sound was raucous, tinkling, propulsive. Intrigued, I walked up the hill from Broadway and found myself in the middle of a huge block party, a thousand people strolling, chattering, mingling, lazing back. This, I would learn, was part of the Jazzmobile summer concert series that ran every Wednesday evening. The Jazzmobile itself, a drive-in stage, was parked in the middle of the plaza at the top of the hill, facing the marble steps and high white columns of Grant’s Tomb.

I was, I quickly realized, one of a handful of white people in an otherwise all-Black crowd. Although I felt my whiteness acutely, I soon began flowing north with other strollers toward the food vendors and men in colorful robes selling essential oils. Sweet incense drifted through the humid summer air; I heard every sort of accent—Caribbean, African, hard-edged Bronx. The vibe was peaceful, relaxed, buoyant with an energy that came from somebody blowing hell out of a trumpet mixed with tinkling piano and drums. I bought a plate of curried goat on dirty rice with stewed cabbage and sat down on an open stretch of marble bench. I ate slowly, kept my eyes open without staring at anybody, soaking it all in. The way people greeted each other—loudly, happily, demonstratively—made the occasion feel like a family reunion.

Later, I squeezed back through the crowd, getting close to the stage. A sign next to the Jazzmobile said, “Dizzy Gillespie and his Orchestra.” The Dizzy Gillespie? There he was, big-bellied in a blue T-shirt, mopping sweat off his face with a white towel. His trumpet was bent, angling up toward the darkening sky. He leaned against the front of the piano, relaxed and informal, and sang “Swing low, sweet Cadillac, comin’ for to carry me hooooooooooooome!” as everybody around me, the whole plaza, roared and cracked up. Later, as I headed home, I could hear Dizzy and his band playing on behind me, the music rippling with good feeling.

Summer Wednesdays at Grant’s Tomb became something I looked forward to. I saw Art Blakey’s band up there in 1982 with Wynton and Branford Marsalis; the same band a few years later with Donald Harrison and Terence Blanchard; singer Betty Carter, who swaggered and yelled at her rhythm section; an aging Lou Donaldson playing “Alligator Boogaloo”; Dr. Billy Taylor on piano, lecturing us between songs about the history of jazz. All the energy of the crowd fed into the music. I knew there was magic at work, but what exactly was it composed of?

I hadn’t yet had the stunningly obvious insight that the people who attended these events, Harlemites descending on Morningside Heights, just wanted to be free. I hadn’t yet realized that every single element of those Wednesday evenings at Grant’s Tomb—the sputtering high-note solos, the potpourri of smells and tastes from the Caribbean and beyond, the styling and profiling and mutual checking out of young men and women and those who had once been young and were hanging on regardless, the loud greetings, slapped hands, and bumped elbows, the flowing movement of bodies easing gently past one another, the lack of assigned seating, the majesty of white marble and the down-home practicality of the tenting and cooking equipment back behind it, the free-for-all entrepreneurialism, the lack of a cover charge—was part of the whole. The musicians felt that whole for what it was, harmonized it and punched it up, and sent it back into the crowd, the soundtrack of free people grooving on freedom.

By the mid-1980s, I had gotten into the habit of blowing harp as I walked the streets of New York, no matter what neighborhood I was in. One day, a young Black man my age sidled up next to me when I was doing this down in the West 20s. He listened for 30 seconds, grooving, and then we started talking. The sound of harmonica is a universal catalyst. Play it in public and people will approach you. This guy told me his name was Kevin Rollins and said he was a nephew of the jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins. He told me I ought to go to the Wednesday jam session at La Famille, a restaurant and jazz club up in Harlem where he worked as a dishwasher. He pronounced it La Fah-MILL.

“They’ll like what you doin’,” he said. “It’s a fun time.”

I’d paid a lot of dues by that point. I’d been to Europe and back, twice, busking the streets of Paris, Avignon, the French Riviera. The previous summer, 1985, I’d followed and learned from Nat Riddles, the Black New Yorker and blues harmonica legend who became a big brother to me, the mentor I was hungering for. He showed me how to tongue block and gave me study tapes filled with Arnett Cobb, Willis “Gatortail” Jackson, and soul-jazz guitar, modeling the busking life with his crowd-stopping performances at the Astor Place Cube. I’d woodshedded incessantly, sat in with a dozen different bands at Dan Lynch, Abilene, and other downtown clubs. I’d played solo on the streets after Nat got shot and fled to Virginia, then hooked up with a manic young guitarist named Bill Taft and busked New York’s streets and subways all autumn, before he, too, left town. I had lifted myself into a new life, a radical makeover of the young white literary journalist I’d been. Harlem was the next step, a huge step. The size of the step scared me. But you can’t end up somewhere new if you don’t risk failure.

So on a cold night in February 1986, I drove down from my new apartment in Inwood, at the top of Manhattan Island, and parked on 125th Street in central Harlem, west of Fifth Avenue. I asked a couple of young guys loitering in front of a bodega where I could find La Famille. It turned out to be just around the corner, on a part of Fifth Avenue that looked like a cozy side street because it dead-ended at Marcus Garvey Park. I hesitated on the threshold, then stepped inside. There was a tiny stage to my left with drums, a Hammond B-3 organ, a stool, and a mic on a stand. I was the only white face in the room. No big deal, I told myself. Just be cool. I moved forward into the smallish room, smiled at a well-dressed couple in a booth on the right. I asked about Kevin Rollins. They hadn’t heard of him. Nobody had. I heard several people murmuring “white boy.” Trying to remain cool, I eased toward the small bar and ordered a Heineken. (Many years later, it would occur to me that the black leather bomber and blue jeans I was wearing—the Fonz look—might have led people to assume I was an undercover cop.)

My best move, I decided, was to connect with the musicians. I went back toward the front and chatted with a man in a light blue fedora sitting across from the stage. John Spruill, rhymes with pool, Panamanian, mid-40s, an organ player—although he wasn’t on the gig that night. For some reason, he took me under his wing. I told him I was a harmonica player looking to sit in.

“Talk to Tippy,” he said, nodding at the tan, clean-shaven trumpet player who had just walked onstage. “He’ll get you up. Second set, though. Wait until the break.”

I noticed a little sign in the front corner of the stage: the Tippy Larkin Trio.

I sat with John at his booth and finished my Heineken, then ordered another and another after that. Three beers didn’t begin to counterbalance the adrenaline flooding through my bloodstream. The music, when it started, was thrillingly alive and propulsive, swinging in at least four dimensions, not the three I was used to. The organist, a stooped older man with a ragged graying beard, bad teeth, and tinted red-framed glasses, was playing with both hands and both feet. It’s possible, I thought, that I am in over my head. There was no guitar to serve as anchor, and I had trouble hearing the chord changes in the organ’s huge swirling wash. But the warmth of the music was what amazed me, the vividness. It was like tasting homemade gumbo made with real roux after spending your whole life eating the slop prepared from a boxed mix.

Eventually, impossibly, the moment arrived. Tippy Larkin held up the cocktail napkin on which I’d written my name. “Ladies and gentlemen, I’d like to introduce a young man who’s going to play some harmonica. Will you please welcome … Adam Gussow.” He mispronounced the first syllable “Goose.”

As I walked the five feet to the stage, the scattered applause died out. “Don’t touch the mic,” Tippy warned.

I turned toward the drummer and organist and said I’d like a B-flat blues, medium shuffle. They chuckled when I pulled out a harp.

“Okay, man,” the organist grunted. The drummer counted it off, and they hit it. And we were swinging.

There was an immediate hush. People were listening for something. I locked into the groove—it was hard to miss—and ran some basic changes, boogie-woogie style, the way you’d show a dance teacher that you knew how to count off the steps, but swinging hard at the same time, pushing against the groove without forcing the tempo. A couple of people started clapping along. Then a guy in back, a young trumpet player I’d chatted briefly with at the bar, called out, “Don’t stop!”

Provoked, I wailed like a lost child on the four-hole draw, the basic power move that every harp player knows. That broke things loose. “Blow!” somebody shouted. “All right now!” The energy level soared in a way that almost knocked me off my feet, but I had just enough experience to recognize what was happening and to hold on. I was suspended in a force field—drums kicking me from behind, organ washing over me, John Spruill shouting on my right, a huge wave of hungry attention pouring down as I stood in the spotlight, feeling it in my throat, the sudden ache, and now I was almost desperate because I’d wanted this for a long time—it was like coming home into the music, walking through a door into the place where the music lived. I reached down into my throat with tongue and lips and wrenched out the bluest blue third I had, halfway between major and minor with a rising edge—wrestling it into place, struggling to hold it—and then I cut them hard with that knife edge, the whole room. And they felt it. They felt me. They were shouting at me, happy. On and on and on we went.

We finally swung to a close, and the place exploded. I stood there stunned. Relieved. My whole life, people had been warning me to stay out of Harlem. White people. Now this.

I glanced at the organ player. He smiled behind his tinted glasses, gestured at the mic. “Play another one,” he croaked.

Four days later, my Harlem education kicked back into high gear at a club called Showman’s, half a block south of 125th Street on Frederick Douglass Boulevard. I’d seen a little ad in the back of The Village Voice for a Sunday jam session starting at four; I jumped in my car, drove down from Inwood, and walked in at six. Nothing was going on. Maybe a dozen people were scattered across the room—relaxing at tables, nursing drinks at the three-sided bar. Tippy Larkin was there, wearing the same blue blazer and tan slacks. The drummer, Phil Young, was setting up on the big low bandstand. Tippy looked up and smiled.

“Maurice, right?”

“Adam.”

He laughed. “You know you all look alike.”

I asked about the jam session.

“Chill out, brother,” he said in a friendly, jaunty way. “We’ll get there.”

Bit by bit, the evening assembled itself as I sat there drinking—the crowd filling in, everybody well dressed and most of the men wearing sharp hats; John Spruill coming through the door, missing me as he skirted the tables and sitting down at the organ, fingering a few chords, then spying me and hopping up to grab my hand; John and Phil kicking the groove into motion; Tippy leaning back on his stool, trumpet flashing as he quietly spattered the head for “Take the A Train.” By mid-set, the house was full, a percussionist had heaved his conga onstage and was slapping and bopping away, and there were two sax players up there, one Black, the other white (Lonnie Youngblood and Jim Holibaugh, I found out later). Then the band was kicking into “Tenor Madness,” a hard-charging jazz-blues I’d jammed on a few times in the downtown clubs. I checked my harps and found the right key. After the full ensemble played the head, Tippy stepped off the bandstand and I saw my chance. I got up off my barstool, leaned over, and asked him if I could get up and blow after the sax players had done their thing.

“It’s in B-flat,” he said.

I patted my pocket. “I’m ready.”

“Your move, baby.”

I walked onstage, squeezed in behind the white sax player, and shouted in his ear that Tippy had given me the go-ahead to blow third, after him.

“Cool,” he said.

Then he bit down on his reed and started wailing, accelerating into a ferocious streaming blast—he was no white pretender but the real thing—and I suddenly thought, Oh shit. The beer and adrenaline were boiling through me, wrestling for dominance, combining and recombining like epoxy starting to smoke and fume. I took a deep breath and dug deep. What was my strategy? Then it came to me: differentiate. There were a zillion things these guys could do that I couldn’t match, but there was one thing I could do that they couldn’t match, which was play harmonica. I had that sound.

I took a step toward the mic as the white sax player finished up, raised it to face level, and let things die down. It was risky leaving that much space, because the rhythm section kept cooking along regardless. I had to keep an ear out for the chord changes, stay locked into the 12-bar cycle as I was surveying the room, and keep breathing, taking it all in as the riff came to me. Don’t overthink it. Just feel it. Hit the two-hole draw, the tonic note, five times, softly: bum bum bah-bah BAH. I could feel things shifting around behind me, heard Phil give a little rim-tap, a “Yeah, buddy,” and I did it again …

Bum bum bah-bah BAH.

And he hit the last three accents, with a POW! on the last one so perfectly propulsive and well calibrated, you’d have thought we’d been playing together for years. I heard John call out, “That’s right!” and I did it again, Phil kicking me even harder from behind.

Bum bum bah-bah BAH!

And then, as calls and shouts filtered into the mix from around the room, the two saxes suddenly swooped in from the side on a little improvised riff that fit between my riffs, like a Kansas City horn section from the 1930s.

Before I knew what was happening, I was roaring down the road in the cockpit of a turbocharged Lamborghini, feeling the explosive power as we shifted and throttled up. I’d never come close to commanding this sort of pedigreed excellence, but somebody had handed me the keys, thrown me into the bucket seat, put my hands on the wheel, and said, “Go ahead.” And I did.

I was driving through Harlem in late October of that year, cruising across 125th Street, when a faint bluesy roar caught my ear shortly after I’d passed the Apollo Theater. I crossed Seventh Avenue with the State Office Building rising on my left, eased slowly past the bus stop, then glanced right and saw him in front of the New York Telephone office.

It’s that guy, I thought. And almost without thinking, I pulled the Honda to the curb, parked, and got out.

An older Black man with a grayish beard and graying cornrows was playing electric guitar through a pair of Mouses—the same battery-powered amp I’d been using—and keeping the beat on a hi-hat cymbal. He was singing hoarsely through another amp, almost shouting, his words partially drowned out by the guitar.

I was thrilled to have stumbled across this particular musician again. Two and a half years earlier, strolling in Morningside Heights on a mellow spring evening, I’d paused to watch a trio of blues musicians on the corner of 113th Street and Broadway: two guitarists backed by a drummer. The guy with the gray beard was the front man. He was drinking heavily—upending a paper-bagged 40 ounce and draining it as he rocked back on his heels, shuddering in a comically exaggerated way, as though the booze was ripping down through him, then strumming a shuffle groove with an incredibly catchy backbeat. “Oh baby,” he sang, “You don’t have to goooooooo …” I was blown away by his music, intimidated by his power and presence.

Now I’d found him. I leaned back against my parked car, watching him go, astonished once again by his deathless groove, his rasping voice. He was two steps lower down than Tippy Larkin and the other jazz cats and soul men I’d been jamming with in the clubs. His take on the blues was closer to my own guitar-driven sweet spot, but with a wild-eyed funk edge propelled by complex inner voicings.

I leaned toward a guy standing on my right and asked who the musician was.

“Who, him?” he said. “That’s Satan. Everybody in Harlem knows Satan. Uh-huh. That’s his spot, right there.”

Satan? I thought.

Although we wouldn’t end up calling ourselves Satan and Adam until we recorded our demo in 1990, the seeds of our duo’s name were planted in that moment. The union-of-opposites theme was baked in.

“Do you think he’d let me sit in?” I asked. “I play harmonica.”

“Harmonica?” He chuckled. “Stevie Wonder, my man.” He extended his hand, and we slapped five. “Sure, he’ll let you play. Can you play?”

“I can play,” I said, surprised at my own boldness.

“Yeah, I think Satan will do that.”

His name was Duke. He called me Adams. I told him I’d be back tomorrow with my stuff.

The next day at noon, I spun out the door with a daypack over my shoulder and Mouse dangling from my hand. I jumped in my Honda and flew down the West Side Highway, exiting at 125th Street, pushing into the heart of Harlem.

Satan was playing the same spot, just east of Seventh Avenue. The weather was lukewarm and calm, one of those Indian summer days New York sometimes gifts you with. I pulled to the curb. Duke was there; I jumped out and grabbed hands, then leaned back as Satan roared on. My heart was thrumming, my whole body. It was La Famille all over again.

Satan finished the song and leaned forward to adjust his hi-hat, which was sitting on a big dirty square of cardboard. He’d kicked it so hard that the cardboard had slid forward, away from his chair. He tugged it closer.

I slid toward him, leaned down, and thanked him for the music. He smiled distractedly as he glanced up at me.

“Thank you, sir.”

“Do you … think I might be able to sit in on a song or two? I’m a harmonica player.”

He continued to adjust. “Where are your instruments?”

I jerked my head. “My Mouse and harmonicas are in the trunk of my car. I won’t embarrass you,” I added.

A few seconds went by. Then he made a big beckoning motion, like he was tossing a tennis ball back over his shoulder. “Come on up!”

A crowd began to form the moment I set my Mouse on the sidewalk and began plugging things together: mic, digital delay pedal, cable. When I was ready to go, Satan kicked into gear, a fast groove in E. I did my best to hold on. People were shouting from all sides as I wailed. We played for what seemed like forever but must only have been six or seven minutes. Satan brought the song to a close with a withering flurry of guitar and cymbals as I screamed on a bent 10-hole blow. Sidewalk traffic had frozen. The intensity of the response was hard to believe. Several guys grabbed my hand, asked me where I was from. Dollar bills and change tumbled into the blue plastic bucket between Satan’s legs, where the mic stand was planted.

The name on his driver’s license was Sterling Magee, but he never used it and didn’t want it used. Over the first couple of years that we played together, people filled in bits and pieces of his backstory: his band work as a guitarist with King Curtis, Etta James, Little Anthony and the Imperials; his singles as a solo artist in the ’60s and the album he’d made with George Benson and the Harlem Underground in 1976, including the song “Funky Sterling”; his time as a Brill Building songwriter with partner Jesse Stone.

Our musical partnership would endure for 34 years, until Satan’s death from Covid-19 in September 2020. My journal tells me what else happened on that day we first played together—October 23, 1986. At noon, according to The New York Times, a group of 800 peace activists marching for nuclear disarmament walked across the George Washington Bridge and continued south to Grant’s Tomb. Half of them had walked all the way from Los Angeles, straight through the desert, the heartland, in seven months. Judy Jones, a participant from Coronado, California, sent home the following account to her local newspaper:

After leaving Grant’s Tomb, we march through Harlem toward our campsite at Randalls Island. Looking up at the decaying buildings, I see children peering out of broken glass windows covered with burglar bars. I am surrounded by Harlem’s colors, spirits, smells and yells. A spiritual band follows us down the street, and a man playing and singing blues on the sidewalk gives several marchers a chance to unwind and boogie.

That bluesman was Satan—Mr. Satan, as I quickly came to call him. (He called me Mr. Adam, and I returned the favor. Everybody else followed suit.) He told me about it two days later, as we were standing next to his old white Chevy step van out on Seventh Avenue, after playing a couple of sets at a nearby discount emporium.

“I could have kicked you in the butt!” he chuckled. “That whole damn march came by right after you left the other day.”

“On 125th Street?”

“You darn right. Thousands of ’em, right after you packed up.”

“Oh shit,” I groaned. “I had a job to get to! I was late for my tutoring gig.”

“I was mentally putting my foot in your behind!” he roared.

That’s how we talked, in full public view on one of Harlem’s big boulevards, after knowing each other for only two days: a 50-year-old Black guy and a 28-year-old white guy. There’s something about grooving with another musician that tends to break down barriers, but I’d never experienced this sort of immediate connection before.

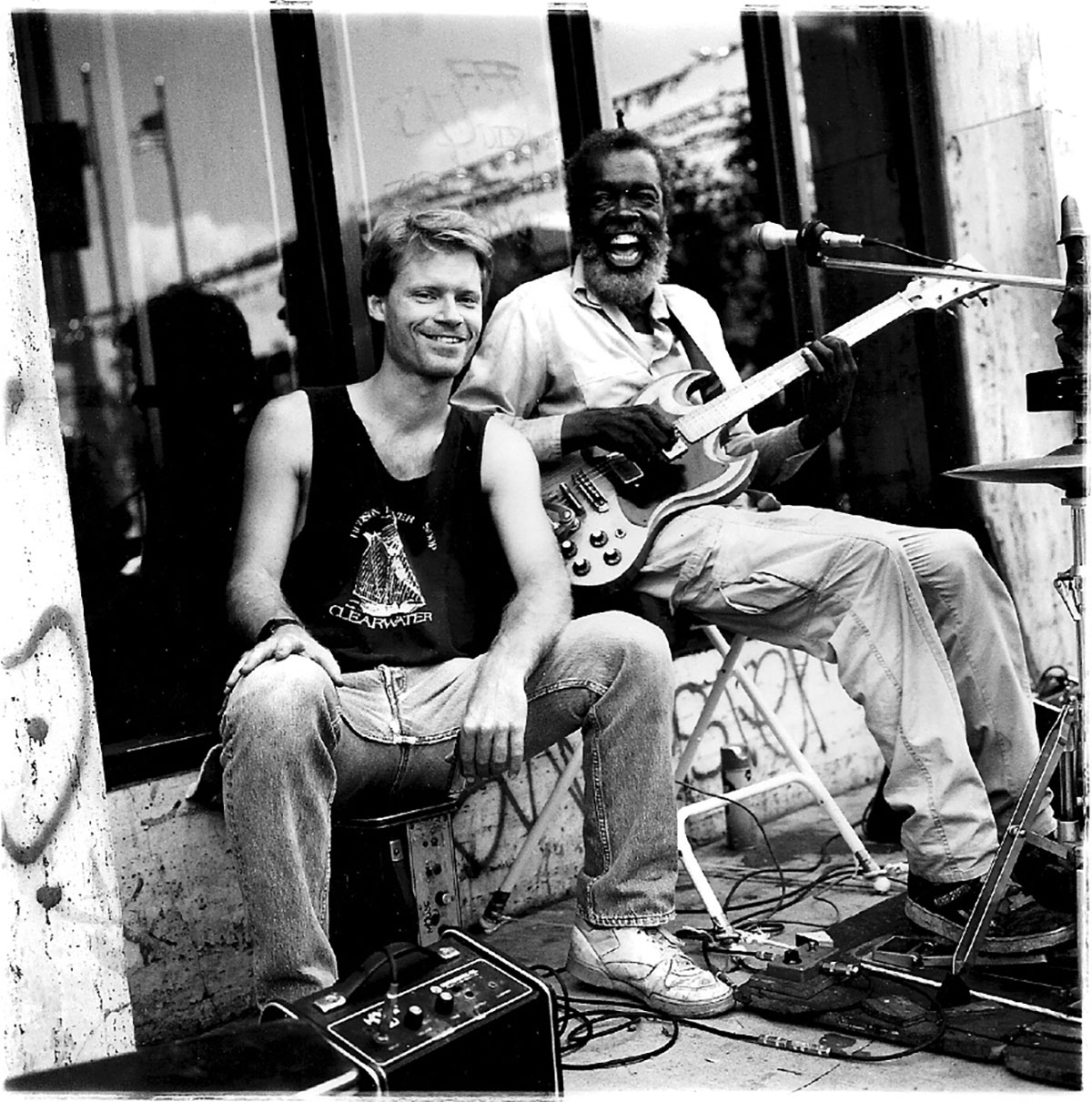

Mr. Satan and the author in Harlem in 1989 (Danny Clinch)

I first became aware of the phrase “beloved community” a year or two after that debut. I was reading James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Malcolm X, Albert Murray, W. E. B. Du Bois, whatever I could get my hands on, trying to make sense of the experiences I was having down in Harlem. I picked up Stephen B. Oates’s biography of Martin Luther King Jr. and was struck by a statement of King’s that gave shape to the partnership that Satan and I were in the process of forging. “We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny,” King had written in his 1963 “Letter From Birmingham Jail.” Six years before that, while discussing the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he had written, “The ultimate aim … is to foster and create the ‘beloved community’ in America where brotherhood is a reality. … Our ultimate goal is genuine intergroup and interpersonal living—integration.”

“Getting it together,” a phrase I heard a lot in Harlem, is the musical equivalent of working toward beloved community. Like beloved community, it has an individual and a collective dimension. You get your own thing together—you woodshed specific songs and techniques, you and your axe, striving for a soulful sound—but musicians who work side by side also seek common ground, especially with regard to volume, pitch, and groove, in a way that isn’t obvious to outsiders but that makes a huge difference to the players themselves.

Early in our relationship, as Satan and I were getting things together in that fashion, a third musician was part of our group: a washtub bass player named Bobby Bennett, a.k.a. Professor Six Million. A slim, acerbic, bronze-skinned man with a hoarse voice and a harsh laugh, Professor—as Satan called him—was an unlikely agent of beloved community. He and Satan had an uneven relationship—bickering like brothers one moment, laughing uproariously the next. They said “shut up” a lot, in a fond way that meant, “Hush your mouth.” I quickly took that sort of incoming fire from both men, and was happy for it. I was part of the team.

We were all aware that race relations in the city were toxic—at least to judge from the headlines and the way they skewed the feeling in the neighborhood. There was a trilogy of low points during our half decade on 125th Street, a murderer’s row of troubled locations in which Black men and boys died at the hands of white men and boys: Howard Beach, Bensonhurst, Crown Heights.

I’d spent Christmas of 1986 out in California with my family. When I got back to New York in January, the city was still aching from what had happened in Howard Beach, where a mob of white teens had chased a group of Black men out of a pizzeria and across a highway, resulting in the death of 23-year-old Michael Griffith. Mayor Ed Koch described the killing as “the kind of lynching party that took place in the Deep South.” The New York Times and the tabloids ran garish front-page headlines, day after day. I hadn’t seen Satan in a while; it was just warm enough, about 45 degrees, that I thought he might be out there. So I drove down to Harlem one afternoon and rolled to a stop at the place where we’d first jammed a few months earlier.

Satan and Professor had just finished packing up. Satan’s amps and percussion were loaded into his shopping cart; Professor had tossed his broomstick and clothesline into his old metal washtub. They were bickering, scowling.

“Well now,” sneered Professor, eyeing me as I came up.

“Hey, Mr. Satan, you’re packing up?”

He glanced up. “Hey, Mr. Gus.”

“We just talkin’,” Professor said, spitting toward the curb.

“Let’s play over by Columbia,” I said. I’d dropped out of the English PhD program there the year before.

Satan stroked his beard and thought. We’d made the quick hop once back in November and done well.

“You have your Mouse with you?”

“It’s in the car.”

Suddenly he broke into a grin. “Hell yes! Let’s drive on over and collect some of that good green money they’ve been holding for us.”

We set up on the sidewalk in front of the Broadway Presbyterian Church steps and ended up staying until dusk: two older Black men and one younger white man making music together on a cool January day, two weeks after Michael Griffith’s death. There was something uncanny about the smiles on people’s faces as they pitched dollar bills into Satan’s open guitar case; you could almost feel them feeling themselves contributing to a righteous cause.

“Kicking ass and stomping dick” was the phrase Satan and Professor had used to describe our playing. Was blues performance a kind of symbolic violence—a recapitulation of the violence that circulated out there, in the social world? Or was it a healing spell against such violence? Or was it both things at the same time? I didn’t know. But I knew that we were doing something useful just by being there, making the racket we made as people strolled by and paused to watch.

We were crowing as we drove back to Harlem that evening. Money and music will do that.

The duo performing downtown (Corey Person)

Two days later, we played out on 125th Street, another cool gray January day. Satan was scowling when I arrived—he’d been there since 11; Professor had shown up at one—but the moment I plugged in, we were kicking and stomping, the music was flowing, and the bills were fluttering into the tip bucket. I was filled with jumping energy, hungry to blow. I’d already learned how to discipline that feeling, falling into formation behind the others, weaving my riffs between the vocal lines, waiting for Satan’s call. “Blow on, Mr. Adam!” he’d shout into the mic. And I’d blow.

Letting my eyes drift toward the big vertical sign for the Apollo Theater, a block down on the left, I’d gaze at the endless parade of bundled-up Harlemites: puffy goose-down coats, black leather coats, and brown suede coats, cheap navy watch caps and spiffy Kangols and fedoras, big white high-top sneakers like the rappers wore on MTV, lots of blue jeans and black jeans and Timberland boots, men in suits with mufflers flapping around necks. Women, too: groups of schoolgirls giggling and shouting, elderly church ladies glancing sideways at me through spectacles, drop-dead beauties my own age and 10, 20, 30 years older.

Out beyond the sidewalk was the usual mix of Transit Authority buses with whooshing diesel engines, bright yellow taxis, freshly washed Lincoln Town Cars sporting livery plates, beaters grimed with winter dirt, plus a steady stream of gold-trimmed, pimped-out white Lexuses and Benzes with fancy chrome rims, sound systems thumping like pile drivers as sullen Black male voices talked trash over hip-hop beats.

This particular day, with the troubles at Howard Beach still dominating headlines, was charmed. “We are the Creators!” Satan roared into his mic. “We are a threesome! And while you’re at it, put your hands together for the young man! He’s been blowing that thing!”

Satisfying as the music was, big as the crowds were, most of the action took place between sets as Satan and I hung out near our amps, gabbing with whoever came up. I kept assuming that somebody was going to give me grief for what had happened to Michael Griffith, but nobody did. Just the reverse: when I mentioned “that bullshit out in Queens,” the person I was talking to made it clear that we, all of us up in here, were on the same side.

“I slapped hands at least two hundred times this afternoon,” I wrote that evening in my journal. I was an avid journal keeper back in those days because so much was happening and I wanted to remember it all.

Much later, after we’d packed up and Professor had disappeared, after I’d driven around the corner and down three blocks to Shakespeare Flats while Satan pushed his shopping cart along the same route, we leaned against the side of my car as winter dusk fell in Harlem, tossed back a couple of half pints of Romanoff vodka, and began to make plans: huge plans, staggering plans, plans that had us playing the streets all spring and hitting the road when summer came. Healing the soul of America. That’s when he first called me son.

“I’m calling you son,” he said, “because that’s how I feel about you.”