In the morning, after the rain, I headed for a rusting watchtower at the edge of the U.N. compound to see what water had done to the desert. Already frogs had emerged from subterranean slime chambers and filled the air with their calls, and in the trees starlings and doves with mad red eyes cooed and hollered. I was excited, too. The previous week had been hot and dust ridden, and a thousand years of pulverized earth seemed to scrape inside my eyelids. Clouds had been gathering in grand formations for days, but they always sailed out of Kenya dry and mute, only to be torn open by the ragged volcanoes on the horizon, above Uganda.

I walked slowly through tall grass, careful for cobras and adders and other creatures made truculent by the rain, and the stubborn mud glommed onto my boots in thick, stinking sheets. When I reached the tower, a thin new sound rose above the amphibian shrill. A human voice, high and fair, recited verses in Swahili, crumbled gracefully into wordless humming, and then rose into song. I climbed the tower fast for a glimpse of the singer.

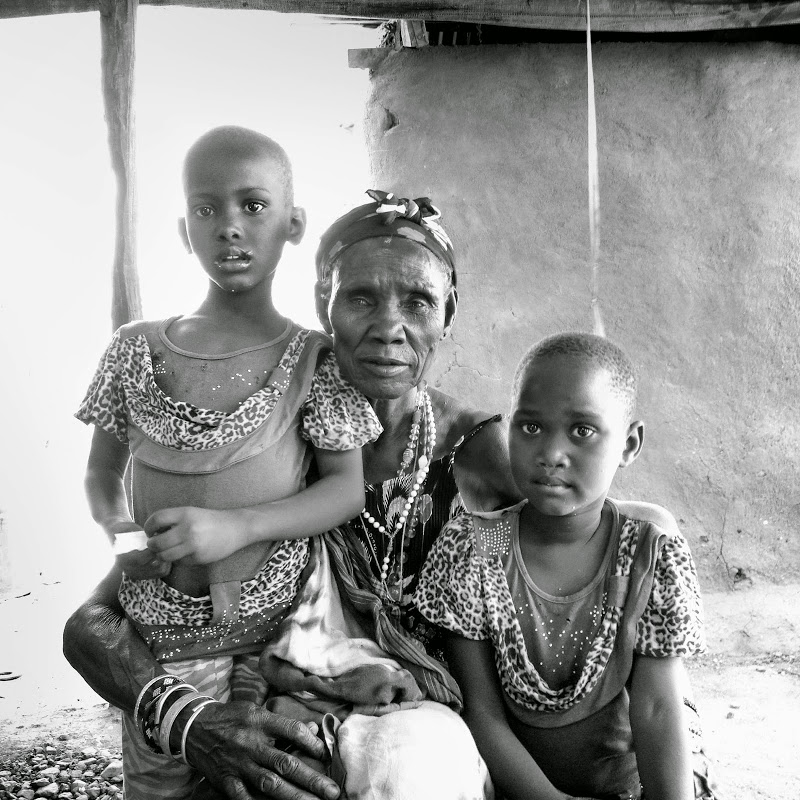

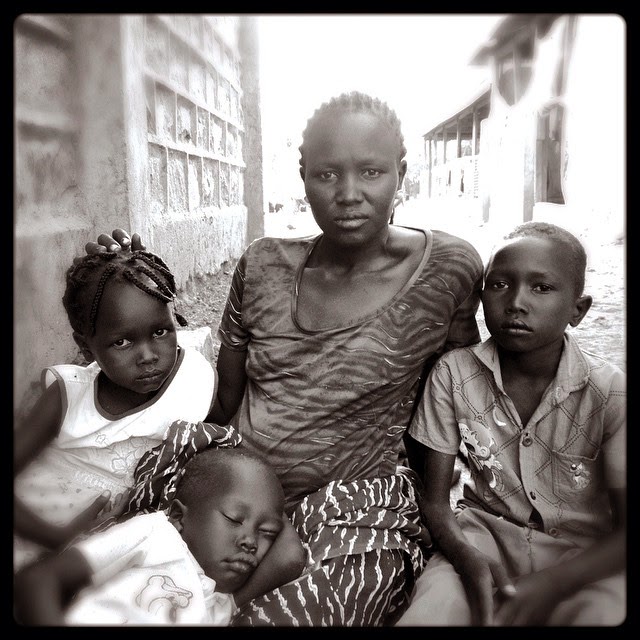

It was a girl I’ll call Leah. Slender and long-limbed, wearing a T-shirt and skirt, she sat on a berm above a big puddle, singing and humming and drawing shapes in the mud with a finger. Leah was a refugee from South Sudan, 17 or 18 years old, depending on the day you asked, and an orphan whose parents were long dead, killed by fighting back home. She had come around a lot lately. At first her appearance, outside the gate of the U.N. compound where I lived, or somewhere in the sprawling refugee camp across the road, had seemed sweet coincidence. But lately the encounters had gotten weird.

Leah had been watching me and my collaborator, photographer Luke Padgett, and had recently come to know which of the compound’s towers we might climb for a view of the desert and when we were most likely to do it. She would suddenly appear wherever we were working, acting furtive and fidgety, sometimes waiting to speak with us, sometimes vanishing before we could greet her. She never demanded money, never requested impossible things. She wanted something, but even she didn’t seem to know what.

This was unsettling. She was alone, all but invisible to the world, one orphan among thousands drifting through a refugee camp called Kakuma. And yet her presence had begun to haunt me, and the idea of another awkward chat—me shouting hello to a teenager, she offering a smile before sinking into girlish silence—seemed ridiculous, guaranteed to make me feel helpless and stupid. Who knows what she got out of it.

Leah did not see me in the tower, and I climbed down. I noticed she was shoeless, and her pale soles were somehow unmuddy. She went on singing, the beauty of it undiminished but now melancholy, unanswerable against the screeching frogs. Later I learned that she had been waiting specifically for me. In her hand she carried a small bracelet made of bright beads, my name misspelled in white across its face.

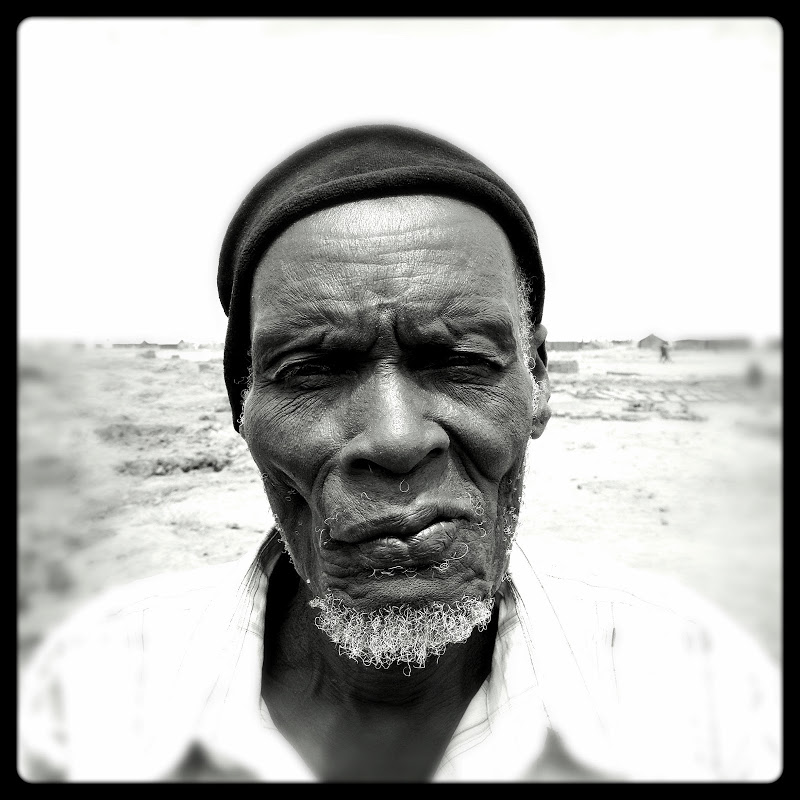

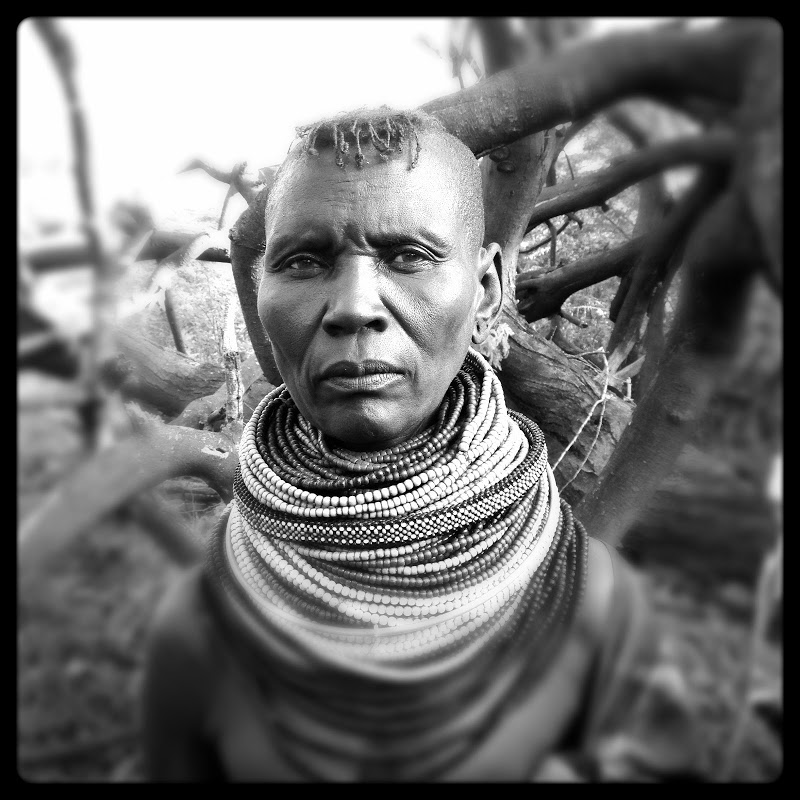

The near encounter happened late last November, when I had been at the Kakuma camp in northwestern Kenya for a month, working on a documentary film about refugees. The camp, which is managed by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, sprawls across almost 10 square miles and is home to 180,000 people from more than a dozen African nations and, now and then, to a stray Iranian or Russian. Most of the refugees at Kakuma are Muslims from Somalia or, like Leah, Christians from South Sudan. Other groups include Pentecostal Rwandans, Catholic Congolese, and Orthodox Ethiopians, some of whom have spent 20 years waiting to be resettled somewhere else.

In most ways Kakuma is safer than scores of African cities and even some comparably sized ones in the United States. Perhaps it’s because people who arrive here from the battlefields, failed nations, and oppressive corners of the continent have seen enough bloodshed; perhaps something drains away when the tired construct of statehood dissolves. The camp is not without trouble, though. Domestic violence is common, and sexual attacks also occur, although both are hard to quantify. And because the camp is so diverse, Kakuma sometimes sees flares of intertribal combat and score settling.

Just before I arrived here last year, fighting between the Dinka and the Nuer—Sudanese tribes that have been rivals for generations—exploded. Eight people were killed, many were wounded, and a chaotic reverse tide of more than a thousand refugees fled the camp into the Kenyan town beside it. When my plane was landing at the town’s small dirt airstrip, I saw them crowding into churchyards, swarming onto the grounds of the police station, wandering in the dry riverbeds. Most, I discovered, were from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. More than one said they learned long ago to run at the first sound of trouble.

But such conflict is unusual, and people keep coming. Since December 2013, 45,000 Sudanese have poured across the Kenyan border toward Kakuma, fleeing civil war in their newborn country. For others, including the Congolese, Kakuma has become a sought-after destination, by virtue of its general peacefulness, the apparent quality of its schools, and certain persistent rumors, including one that if you make it to Kakuma, your chance of earning passage to the United States is improved (it isn’t true). A former official at the camp, a Frenchman, told me large groups of children sometimes arrived at Kakuma, sent across deserts and borders by hopeful parents.

“I’ve never seen anything like it in 20 years of working with refugees,” he said, speaking not only of the children but also of Kakuma itself. “It is an amazing place.”

And yet it is still a modern limbo. Even the name Kakuma, its origin unclear, is sometimes said to mean “nowhere.”

I first met Leah along the western edge of the camp, on a rise above a lagga, a dry riverbed. She was in a crowd of men, women, and children making bricks. The U.N. encourages refugees to build their own houses, and most eventually do. There is, after all, abundant mud and enough water with which to make bricks, endless sunshine to bake them, and plenty of time for the project—most refugees will remain here for years, possibly for the rest of their lives.

Leah had recently been kicked out of an aunt’s house for reasons I never learned, and she was making bricks to build a house for herself. When she saw us, she stopped and walked over. A lot of people did that—white guys with cameras are still an unusual sight for many at Kakuma—but in Leah there was a childlike boldness, a fearlessness and curiosity that Luke and I admired. After that we looked for her whenever we worked on her side of the camp, and once or twice I paid her to help translate.

Over a couple of weeks I learned more of Leah’s story. She belonged to the Didinga tribe from Eastern Equitoria, a state of South Sudan, and she told me that she left home after her parents had been killed during the second Sudanese civil war. She was probably 14 years old at the time. Alone, frightened, she attached herself to a group of fleeing neighbors and headed east for Kenya. She never mentioned brothers or sisters or relatives other than her aunt, and when I asked she said she had none.

Like a lot of stories told at Kakuma, Leah’s shifted from day to day, and with each telling. There might have been several reasons for this, including her limited English and my inability to speak her language beyond “Good morning.” But more important, Western ideas about unshakable truth rarely took root in the refugee camp. Not because people were lying, but because they understood fluidity and sensed the absurdity of their situation.

Refugees such as Leah knew how easily community, family, and identity might disintegrate. Every day in the camp you wandered through their stories of flight and transformation, narratives rich in unverifiable detail or dark and impenetrable. Several times I asked Leah why she’d been pushed out of her aunt’s house, or what specifically had happened to her parents. She would grow sullen and silent, and I stopped asking.

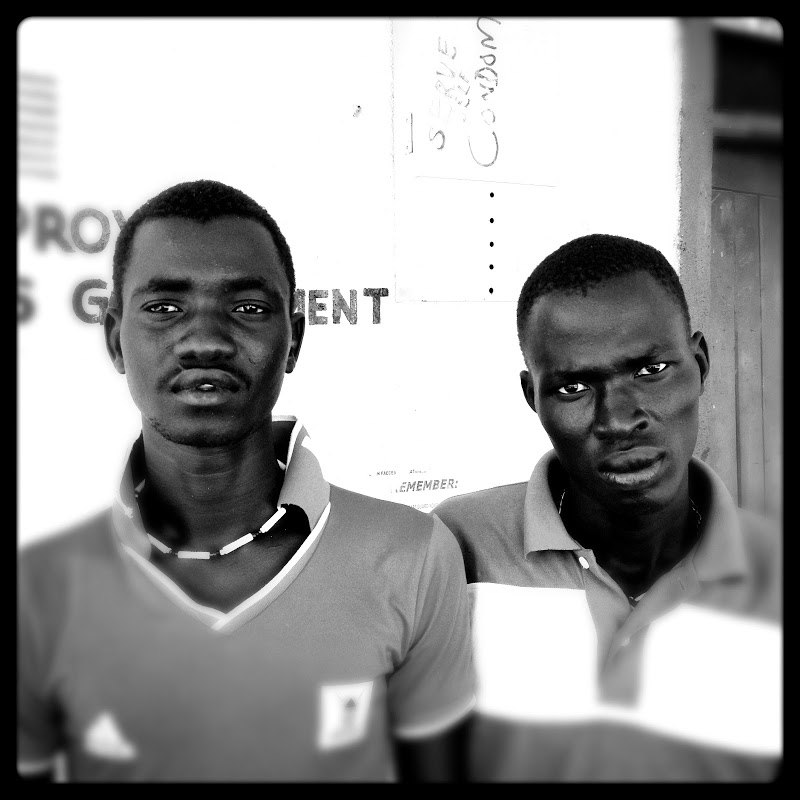

Around this time I noticed that Leah was always uncomfortable around boys her own age. The boldness I had seen earlier did not extend to the teenagers who drifted in packs through the camp—gangly and grinning, handsome in their bright soccer jerseys. She would stop to watch them, but not in longing. She was very pretty, and the boys would watch back.

Early one morning, at the brickyard, she stood silently at my side as I took notes on the ebb and flow of the work. Women and children carried bricks stacked three or four atop their heads, walking up from the pits toward plots where they would soon begin assembling low, rectangular houses. After a while, I asked Leah what she’d been up to, and she breathed in a way that made me look at her. Then she said she’d nearly been raped.

“Yesterday some boys try and catch me,” she said.

“Catch?” I asked.

“My neighbor sent me to fetch something, and when I come, they took me.”

“Took?” My gut lurched.

“I yell and yell, and some Equitorians, they come and the boys run off.”

She did not look at me. I tried to read her face and could not.

“I am not feeling good,” she said, and she did not mean ill. I asked if there was anything I could do, anywhere in the camp I could take her. She shook her head, and we fell again into silence.

After some minutes I asked more questions, as delicately as I knew how. Leah’s answers were vague, the locations and timelines unclear. I pressed a few hundred shillings, worth about five dollars, into her hand, partly in payment for helping translate a sentence or two but mostly because I didn’t know how to help. Once more I asked if she wanted to come with me. She said no. We walked in silence until we reached her rambling brick pile. Then I went on alone.

That night I searched for options. I thought I could find a way to help Leah, but the U.N. officers I spoke with, patient and jaded, told me there wasn’t much to be done. If she was 18, she was old enough to fend for herself. If 17, she’d probably have to do that anyway. She might go to the Kenyan police and file a report, but we all knew that wasn’t going to happen. The police were considered violent and untrustworthy, and they had a reputation for blaming victims of sexual assault.

Her orphan status didn’t push her to the front of any lines, either. There were many orphans at Kakuma, and many of them were much younger than Leah. In the end there seemed only one route open: to apply for resettlement in the United States or some other country, which for most refugees is the equivalent of a Hail Mary. Leah had never tried. She’d only once mentioned America, in a whisper, saying, “I want to go there someday.”

Over the next few weeks, as my reporting shifted to other areas of refugee life, Leah started seeking Luke and me out. One morning she showed up at the front gate, but we did not see her; a guard said that she’d come looking for me. Other times she appeared pacing back and forth below the watchtower. She always told us she was looking for firewood, but that seemed unlikely; the area had been stripped of wood ages before.

I guessed that Leah just wanted attention. That she felt safer with us than with other men, safe enough to be curious about life beyond her confined world. Still, it was troubling. In a refugee camp you are constantly asked for things—money, phones, a helpful word at the embassy. You do what you can, and simultaneously you learn to deflect the endless stream of desire. I’d gotten pretty good at it, but Leah slipped through my defenses. She asked for nothing, but in a way her need was louder than all of the rest. I felt ashamed each time I saw her. When she began working harder to find me, I grew angry. What did she want? What could I offer? What was I supposed to do with this kid?

I never found a good answer. The last time I saw Leah was in early December. She had tracked me into the Ethiopian section of the camp, where I was saying goodbye to friends. I noticed her coming up the road, and she gave her awkward smile. When I finished with the Ethiopians she came over and presented the bracelet, the one with my name misspelled on it. She told me she’d been looking for me for days. I laughed and offered her a ride home on a motorcycle taxi. At first she was reluctant, but then she changed her mind and sat sideways behind the driver, holding down the hem of her skirt as we bounced through the camp, dodging virescent puddles and sliding through mud. I noticed she was smiling again, this time in simple joy.

When we reached her neighborhood we stood looking at the brick pits and the new houses rising nearby. After a while a small crowd of boys wandered through, laughing and shoving each other, being boys. Leah went rigid. Slowly she told me they had tried to catch her while she walked in the lagga a few days before.

I looked at her and at the boys and was suddenly filled with rage. They were teens, skinny and pimpled, but I started to walk toward them anyway. My skin tingled, heart pounded. I had no idea what I would do or say but it didn’t matter, for in their giggling arrogance I glimpsed one possible version of Leah’s future, and I saw reflected my own helplessness.

“Don’t,” she said.

“Are you sure?” I asked. “I’ll tell them to leave you alone.”

But my fury had already broken. She was young enough to be my daughter, but she was not. Was I really going to attack children and say I’d done it on her behalf? In a few days I’d be gone, and there was nothing I could do to keep them away for her. She would have to figure it out on her own.

We walked back toward her brick pile, and when we arrived, I saw it was gone. A storm had passed through a few days earlier and her bricks—nearly a thousand of them, one for almost every day of her life at Kakuma—had melted back into the earth. I asked about it, and she shrugged, said she was in no hurry. The days were warm and the nights were warm and she had all the time in the world to start over.