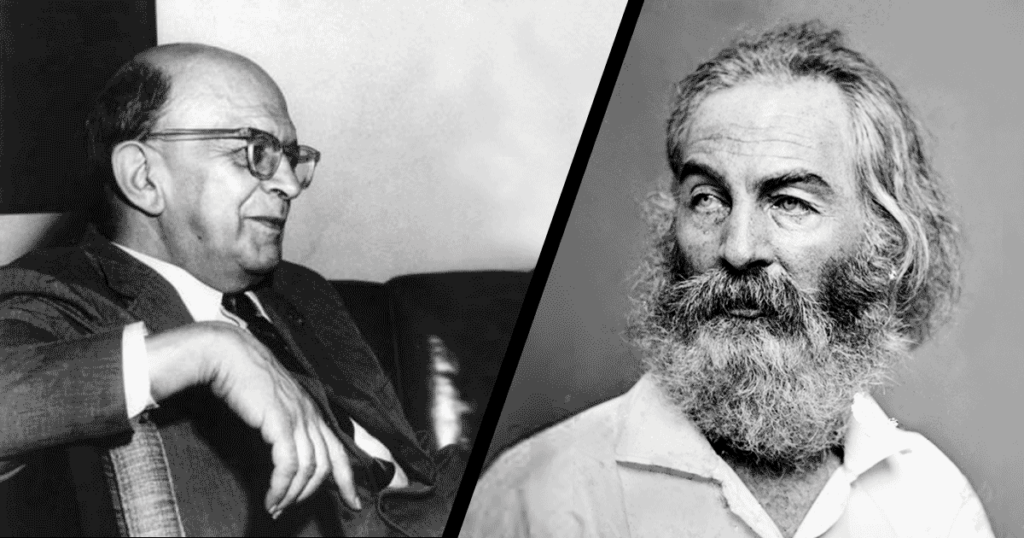

Last week, I wrote about the eminent American composer Roger Sessions (1896–1985) and his searing Eighth Symphony, completed 50 years ago. Sessions happened to be working on another work during that turbulent period, what would turn out to be one of his most enduring pieces: the cantata When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, which takes as its text the famous elegy by Walt Whitman. Completed in the autumn of 1970, the work was dedicated “To the memory of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy”—both of whom were assassinated during its gestation.

Sessions’s acquaintance with Whitman’s poetry dated back to his freshman year at Harvard (he was all of 14 at the time), when he purchased a copy of Leaves of Grass. “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d,” once encountered, lingered in his imagination. “Even during my adolescent years,” Sessions wrote, the poem, “with its moving evocation of the rich American landscape in spring, with its lilacs, its forests, and its thrushes, and of the Civil War, had touched me very deeply.” In 1921, he attempted to set the poem to music, but despite making numerous sketches, nothing he wrote satisfied him, and he knew that some time would have to pass before he could do justice to the text. Indeed, not until 1967 did he take up the project once again. By this time, an elegiac current had been running through much of Sessions’s work. He had begun his Piano Sonata No. 3 (the so-called Kennedy Sonata) in the aftermath of JFK’s assassination, and an earlier piece, the Symphony No. 2, was dedicated to the memory of Franklin Delano Roosevelt—Sessions had been working on the third movement Adagio when he learned of that president’s death.

As for Whitman, the 46-year-old poet wrote “Lilacs” in a sustained white heat, his heart filled with sadness following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865. “The season being advanced,” Whitman would recall, “there were many lilacs in full bloom. By one of those caprices that enter and give tinge to events without being at all a part of them, I find myself reminded of the great tragedy of that day by the sight and odor of these blossoms. It never fails.” Though the poem never mentions the fallen president by name, it is unquestionably an elegy for Lincoln, an incantatory and ecstatic meditation conceived on a grand scale.

So much of Whitman’s verse is musical. “Lilacs” is especially so. As biographer Justin Kaplan has noted, “Few American poets have been as consciously and deeply indebted to music as Whitman.” The poet loved both grand opera and the popular American songs of his day—both influences can be heard in his verse. Praising the song-like qualities of “Lilacs,” Swinburne called it “the most sweet and sonorous nocturne ever chanted in the church of the world.” No wonder, then, that Whitman is the American poet set most often to music. In 1946, Paul Hindemith composed a moving setting of “Lilacs,” but Sessions, who after 1953 or so wrote largely in a 12-tone modernist idiom, interpreted the poem along starkly different lines.

The work—some 45 minutes long and divided into three parts—is scored for soprano, contralto (or mezzo-soprano), baritone, chorus, and orchestra. From the opening, enigmatic passages, the piece is almost unrelentingly mournful. In the brief first part, the three symbols of the work are presented: the lilac, emblem of love, remembrance, and springtime renewal; the planet Venus, the “great star early droop’d in the western sky in the night,” a representation of Lincoln himself; and the hermit thrush, associated with death and its inevitable acceptance. The musical motif connected to the thrush is memorable and haunting—an obsessive, repetitive, and fluttering figure in the flutes and piccolos, a deathly carol that’s a world away from that of, say, Hardy’s darkling thrush, which sounds a note of joyful hope in a desolate winter’s landscape (“So little cause for carolings / of such ecstatic sound …”). In Whitman’s poem, these symbols are interwoven throughout, with power and resonance; so they are in Sessions’s score.

This is music of so many moods and characters, despite the pervasive funereal context. We sense pain, ecstasy, stupor, consolation, and confusion, too, especially in the music assigned to the chorus. I am thinking of the chaotic choral section in part one and the canonical passage beginning, “O western orb, sailing the heav’n!” in part two. We also sense nostalgia, for example, in the long, arcing melody sung by the baritone when describing the old farmhouse with the lilac bush that fronts it. The music soars and crests and undulates, with swirling, strident dissonances. Yet it is also lyrical: few composers could shape a melody like Sessions. In the work’s second part, the music takes on a distinctly American character, with hints of the hymnal and Charles Ives, appropriate given Whitman’s subject matter: the description of Lincoln’s funeral train, the coffin adorned with roses and lilacs, bearing west from Washington, D.C., to Springfield, Illinois. One passage sung by the chorus seems to encompass the totality of the nation:

Over the breast of the spring, the land, amid cities,

Amid lanes, and through old woods, where lately the violets peep’d from the ground,

Amid the grass in the fields, passing the endless grass;

Passing the yellow-spear’d wheat,

Passing the apple-tree blows of white and pink in the orchards;

Carrying a corpse to where it shall rest in the grave,

Night and day journeys a coffin.

Few other musical passages I can think of better convey the feeling of deep, collective grief.

The cantata’s second part is filled with wondrous moments. When I listen to the chorus singing, “Sea-winds, blown from east and west,” I can practically hear the chill and bluster in the air. And when I hear the dark-hued, somber lines sung by the contralto in the middle of part two, Kennedy and King come quickly to mind:

O how shall I warble myself for the dead one there I loved?

And how shall I deck my song for the large sweet soul that is gone?

And what shall my perfume be, to adorn the grave of him I love?

These lines, their music reminding me of the valedictory section of Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde, are pretty much all the contralto has to sing until a moving, extended passage in part three; it’s almost as if Sessions has been holding her back for effect. And sure enough, the autumnal timbres of the contralto voice come almost like a shock after the sonorities of the baritone and chorus:

Come, lovely and soothing Death,

Undulate round the world, serenely arriving, arriving,

In the day, in the night, to all, to each,

Sooner or later, delicate Death.

This is the heart of Sessions’s cantata—the coming to terms with death—and the music is piercing and intense, the soloist’s melodies floating over the angular harmonies of the orchestra. What follows is a volatile sequence in which the soloists and chorus sing as one:

I saw the battle-corpses, myriads of them,

And the white skeletons of young men—I saw them;

I saw the debris and debris of all the slain soldiers of the war;

And we saw they were not as was thought;

They themselves were fully at rest—they suffer’d not;

The living remain’d and suffer’d—the mother suffer’d,

And the wife and the child, and the musing comrade suffer’d,

And the armies that remain’d suffer’d.

Whitman was recalling here what he saw in the war, when he consoled the wounded as an army hospital volunteer. The music captures all of those torrid emotions and the overwhelming nature of the experience—the way the chorus lands every time on the word suffer’d is nothing short of chilling. Given the intensity of the passage, it’s apt that the cantata ends not with a bang but with a gentle fade-out and a whisper. Anything else would have been too much to bear.

Harold Bloom has written that “elegies often have been used for political purposes, as a means of healing the nation.” Frequently, following some national tragedy, I find myself turning to European music for consolation: Mozart’s Requiem, say, or the Adagietto from Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, or one of the sublime Adagios from Bruckner’s late symphonies. But what is America’s requiem, the piece that ought to be played in moments of tumult in order to assuage grief both private and public? I attended a Baltimore Symphony concert very shortly after 9/11, and when the conductor, Yuri Temirkanov, led the orchestra in a performance of the national anthem, many in the audience broke down in tears. But what I am imagining is something longer and more substantive, something that traverses the entire range of human emotion, a great work of art in which music and text and symbol and metaphor work in complex and brilliant ways to bring about solace and catharsis. Roger Sessions’s Lilacs might be that very work.

Although Sessions faithfully adhered to Whitman’s lines, the composer worked from memory, and discrepancies with the poem exist. The extracts quoted here are from the text of Sessions’s cantata.

Listen to Sessions’s When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d, with Seiji Ozawa conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra, the Tanglewood Festival Chorus, and soloists Esther Hinds, Florence Quivar, and Dominic Cossa: