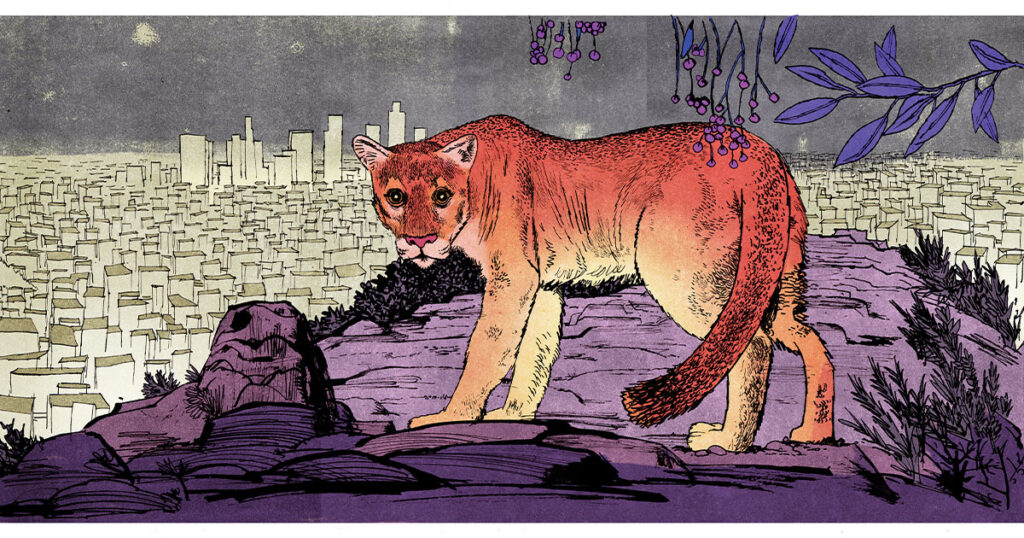

On December 17, 2022, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife euthanized P-22, the celebrated mountain lion “king” of Griffith Park, after he was struck by a car in the Los Feliz neighborhood of Los Angeles. P-22’s death inspired a public memorial concert attended by thousands, coverage in local and national news outlets, a eulogy from California Governor Gavin Newsom (whose father was a founder of the Mountain Lion Foundation), and several murals across Los Angeles. Previously, P-22 had been the subject of books, a documentary, and an Instagram account with more than 15,000 followers. He was arguably the most famous mountain lion of all time and, by some standards, one of LA’s most beloved celebrities.

He was born around 2010 in the western region of the Santa Monica Mountains, where he lived anonymously for the first years of his life before heading east to Griffith Park, somehow crossing the 405 and 101 freeways without being hit. In March 2012, scientists from the Friends of Griffith Park Wildlife Connectivity Study, which had installed cameras around the park to monitor wildlife, found him wandering across one of their screens. Soon afterward, he was caught, christened P-22 (since he was the 22nd puma in an ongoing study), and fitted with an e-collar, which he wore until his death.

Over the next 10 years, P-22’s movements were meticulously tracked, recorded, and publicized. In December 2013, he appeared in the pages of National Geographic, prowling in the darkness underneath the glowing white Hollywood sign. He became the new face of urban wildlife conservation efforts, helping to raise funds for one of the world’s largest wildlife bridges, currently being built over Highway 101. In 2014, he was captured for a routine collar change and treated for a serious case of rat poison ingestion. In 2015, he was discovered in the crawl space of a Los Feliz house. Despite the presence of helicopters and news cameras and numerous flying projectiles—officials shot rounds of beanbags and tennis balls in an effort to flush him out—P-22 refused to leave until the cover of night. In March 2016, the carcass of a koala was found at the Los Angeles Zoo, and though P-22 was captured on security footage roaming the grounds at night, no one could prove—or perhaps no one wanted to prove—that he was the perpetrator.

Despite living in LA for almost two years, I hadn’t heard of P-22 until his death last December. First I saw friends mourning him on social media. Then I noticed his picture in coffee shops. Strangers began striking up conversations with me about their grief. A horse owner in Griffith Park, whom I’d spoken to only in passing, told me in detail about two personal encounters with P-22, both times when she was out late at her barn. With a mystical look in her eyes, she described the feeling of being watched before she noticed the big cat’s golden gaze and slowly backed away.

The descriptions I heard were almost spiritual. It was as if P-22 had been an earthly manifestation of the divine, a sort of miracle, surviving as he did amid encroaching urbanization and highways and rat poison—an icon of hope, of our ability to live in harmony with nature. People called P-22 a hero, a symbol, an incarnation of all that is beautiful and mysterious about nature. But perhaps he was just an animal doing what he could to survive with what he was given. After reading the history of the last 10 years of his life, I kept wondering how wild he really was.

When I was growing up in Monterey, California, encounters with mountain lions often made local headlines. California, along with Colorado, is home to one of the largest mountain lion populations in the country—4,000 to 6,000 by some estimates—so this is no surprise. Occasionally, we would hear of sightings on a neighbor’s security camera or of a dog that had been attacked, but mostly, the big cats kept to themselves, living among us but in secret. As far as I knew, none of them had names.

I was also raised on a steady diet of Animal Planet and nature encyclopedias. By the time I was six, I was at peace watching a lion rip apart a zebra limb by limb. This was the way the world was: wild animals lived only by the rules of survival. It wasn’t good or bad; it was nature. My mother fondly recalls the time I consoled her about the death of a dog in a movie by saying, “That’s just the circle of life, Mom.”

Though I never saw a mountain lion, I encountered “wild” animals every day. The most dangerous of these seemed to be the mother deer—one of them chased my mom and dog all the way home when they were out walking one day. Coyotes also tracked my dog, but they usually kept their distance if humans were around. There were always raccoons, and I seem to remember an incident when one tried to attack one of our cats, but I’ve since learned that raccoons are not aggressive, so I wonder if another animal was to blame.

The less common the wild animal, the more mystical the encounter. Once, in Big Bend National Park in Texas, I was standing next to a clearing when I suddenly felt that I wasn’t alone. When I looked toward the clearing, I saw a black bear about 65 feet away, nosing the ground. I remember being struck with wonder rather than fear. I stayed quiet as the bear looked up at me before eventually shuffling away.

In urban spaces, most of the wild animals we know and love are not in their natural habitats. We see them at a zoo or on a screen, where they exist as celebrities with recognizable names, personalities, and quirks—just like us! They become recurring characters in our lives, and the degree to which they do so seems determined by their perceived cuteness. Vultures, not that cute. Snakes, not cute. But anything with fur, cute. Also cute: fish or amphibians that can be easily anthropomorphized into cuddly friends. Wild pigs enjoying mud rolls or foxes living like pet dogs have become objects of worship. Raccoons—or “trash pandas”—are meme celebrities. The axolotl, a salamander, has become a social media darling for its remarkably human smile. Our culture seems to say, “We love the wild!” Or at least we love our definition of it.

Killer whales, or orcas, are a prime example of an ontological dilemma surrounding our definition of wild animals. Are they killer whales, or are they orcas? Even their unstable name reflects our inability to capture their true nature—and they are among the deadliest predators of the sea. Sure, they can jump through hoops in a pool, but a pod can also take out a blue whale and up to 20 sharks in a day.

For years, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) has been a staunch and vocal opponent of housing orcas in captivity. In 2022, the organization once again criticized SeaWorld, a company it had previously sued after a video of two whales “attacking” each other was released by a concerned patron. A SeaWorld spokesperson said that the behavior was known as “rake marking” (that is, when certain whales and dolphins rake their teeth against one another) and was normally seen in the wild. PETA said that the video was evidence of “horrific attacks.” The question of whether the incident was “normal” or “horrific” strikes me as particularly human in that we believe there is one right answer.

Recently, the Cancun-based Dolphin Company, which operates several aquatic parks, has considered releasing its prized orca, Lolita, from the Miami Seaquarium, where she has lived and performed for more than 50 years. The move could potentially cost millions of dollars and require a military transport plane, not to mention the crew required to help Lolita adapt to the wild. Despite these difficulties, Lolita’s potential release has been celebrated as a win for animal rights. The chief executive of the Dolphin Company, Eduardo Albor, said that she would become a “symbol,” and I don’t doubt that if she is released, this is exactly what she will be, watched and tracked until the day she dies. After all, there’s nothing for us to gain from a whale living her life anonymously in the sea.

P-22’s death also inspired a debate over the body of the animal. To whom did it belong? Scientists had already performed a necropsy and wanted to retain samples of his remains for further testing. Tribal leaders of the Chumash, Tataviam, and Gabrielino (Tongva) peoples, who regard mountain lions as relatives and teachers, wanted P-22 to be buried in his homeland, and as intact as possible. At the time of the burial, it remained unclear whether the groups had reached a compromise. I assume that the location of his burial was kept secret to dissuade pilgrimages to his grave.

The thousands who attended P-22’s memorial in early February saw performances and tributes by DJ and music producer Diplo and actor Rainn Wilson. Chuck Bonham, director of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, described his decision to euthanize P-22 as “gut-wrenching.” (After the car accident, wildlife biologists found that the puma had a fractured skull and diseased kidneys, among other serious ailments.) “P-22 was beautifully abstract,” Bonham said, “the essence of the wildness of wild things.”

Can you know a wild animal to death? What’s most interesting to me about P-22 is this paradox: our insistence on understanding the “essence” of wild animals seems to compromise their wildness. That we saved P-22 from death by rat poison only to kill him “humanely” years later is evidence of our irreconcilable presence in the wild, of our compulsion to mark it with our own values. Do animals suffer as we do? This is a bigger question than I can discuss here, but I think the short answer is that we don’t know. What we do know is nearly the entire life story of this mountain lion—from the moment he appeared on scientists’ radar to the time we decided that his injuries from a car crash were too severe for him to continue living. The possibility that he had suffered before the collision, because of what we as a civilization had done to interfere with his livelihood—this is almost too much to bear.

Tracking P-22 and turning him into a public icon have contributed greatly to scientific knowledge and public awareness of wildlife conservation efforts. I don’t doubt this. What I want to point out is how our obsession with documenting and projecting our ideas of wilderness onto animals defeats the very notion of the “wild.” I wonder whether the urge to deify P-22, to release all the orcas from captivity, and to make cute online memes of axolotls and raccoons is just a way to assuage our guilt. After all, we are the ones who have wreaked havoc on these animals’ lives. We are the ones who have destroyed or degraded so much of their habitat, and I think the fantasy of living in peaceful coexistence with wild animals in urban spaces is problematic, if not potentially dangerous. Do we love wild animals, or do we love the feeling we get when we do our part to save them?

Maybe it’s not just a sense of guilt that makes us grieve the loss of P-22. Maybe it’s a more primal urge, a reminder of the parts of us that remain wild, that are still untamed, that continue to fight for survival. But though it’s better to care about wild animals than to ignore their fate altogether, I wonder what life would have looked like for P-22 if he had lived his life nameless and unseen—living and dying not by our hands but by the rhythms of the natural world that was his.