Listening Anew to an American Nomad

How the Grammys recognized Harry Partch nearly 50 years after his death

In winter 1940, beside a highway in the California desert, a reedy man bends down for a closer look at the road’s guardrail, where someone has scribbled graffiti: It’s January twenty-six. I’m freezing. Going home. I’m hungry and broke. I wish I was dead. But today I am a man … The onlooker feels a pang of recognition. He can hear these words in his head—the beginnings of another song.

That onlooker was Harry Partch, a musician and writer who balked at the strictures of Western music to become one of the most influential avant-garde composers of the 20th century. Few people today have ever heard of him—Partch seemed to position himself very far from folk hero, and he rarely gets mentioned in the same breath as his contemporaries Woody Guthrie or Huddy Ledbetter, better known as Leadbelly, who drew on deep folk traditions for their music. By contrast, Partch has long had the reputation of an iconoclast and a wanderer. His compositions are written for instruments he built and in complex scales of his own devising, thrumming like wild, futurist gamelan performances.

Born in 1901 to former missionaries to China, Partch grew up in the American Southwest, absorbing a mix of American music but looking to ancient cultures for the creative freedom that he craved. He moved to Los Angeles as a young man and briefly studied music at the University of Southern California, then earned money in movie theaters as an usher and live accompanist to silent films. He had his first hobo experience in the fall of 1928, following the California fruit harvest. He composed music to the verses of eighth-century Chinese poet Li Po. Gigs for the WPA in the ’30s and ’40s inspired him to pen a hobo epic, U.S. Highball, first recorded in 1946. Support from foundations and universities allowed him to pursue musical inventions and compositions in the 1950s, and in the early 1960s, he built a studio in Petaluma, California, out of a former chick hatchery. In 1969, Columbia released The World of Harry Partch, his first album on a major label.

Partch died in 1974, the same year he was inducted into the Percussive Arts Society’s Hall of Fame, and since then has been forgotten by much of the music industry. So how did it come to pass that one of his albums was up for a Grammy Award—for Best Album Notes—earlier this year?

MicroFest Records, founded by Grammy–winning producer John Schneider and Grammy–nominated pianist Aron Kallay, boasts a “repertoire that is simply unavailable anywhere else.” In 2021, they released Harry Partch, 1942, a series of recordings—previously believed to be lost—that Partch made at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York. The black-and-white photo on the cover—a moody young Partch in a flannel shirt, pondering a cigarette Brando-style—captures the artist at a pivotal moment in his career. The album opens a window on a young man searching for American identity, and offers a chance for us to consider him anew.

I’ve been intrigued by Partch ever since my first encounter with U.S. Highball, with its curious tunings and ghostly operatic voices, as rendered by the San Francisco-based Kronos Quartet. Subtitled “A Musical Account of Slim’s Transcontinental Hobo Trip,” U.S. Highball invites comparison to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. In eight tracks, Partch journeys from the California coast to the Midwest on a soundscape of intonations, sideways humor, and fear, its sliding scales conveying the thrill and uncertainty of life on the rails.

Partch was documenting a culture sidelined by mainstream America. His meticulous travel journals are filled with sketches, ephemera, and snippets of speech. June 1935 found him on the California coast, taking shelter in government work camps for migrants, many fleeing the Dust Bowl. In musical notation, he recorded the words of a camp official who ordered Partch to get his clothes deloused. In other words, Partch was creating a musical language to express what he heard amid the hobo community that fascinated him.

Life on the road also allowed Partch to explore his sexuality. I spoke with Andrew Granade, author of Harry Partch, Hobo Composer, about the composer’s time in California. Partch lived at a time when it was not safe to be openly gay, says Granade, “but it very much, I think, informed the life that he chose to live.” Gay life “was still something that was not accepted by the culture at large, was in many ways persecuted. … But when he goes on the road, he discovers a culture where it actually is accepted.” Granade points to affectionate letters between Partch and other hobos with whom he had relationships: “He was able to live that lifestyle in a much freer way during that time period than really almost any other in his life.”

Other times, Partch’s creative pursuits required that he return to stable surroundings. To cover his expenses, he took menial jobs and sought proofreading and editing work with the WPA arts agencies. He was not able to get support from the Federal Music Project, but George Cronyn, an editor on the Federal Writers’ Project, was sympathetic to Partch. He wrote a letter reassuring Partch, “Your essay style, combining color with detachment, is a rarity … An outsider might consider you maladjusted; that’s the penalty of looking clearly at a maladjusted world.”

By early 1940, Partch had wrapped up an editing stint for the Writers’ Project and felt the need to pursue opportunities in the east. He hit the road. A few hours’ drive outside of LA, he found himself in the desert crossroads of Barstow, California, where he discovered that memorable piece of graffiti. He wrote later of his discovery that day:

The scribbling is in pencil. It is on one of the white highway railings just outside the Mojave Desert junction of Barstow. I am walking along the highway and sit down on the railing to rest. I notice the scratches where I happen to drop. I have seen many hitchhikers’ writings. They are usually just names and addresses—there are literally millions of them—or little meaningless obscenities … But this—why, it’s music. It’s both weak and strong, like unedited human expressions always are. It’s eloquent in what it fails to express in words. And it’s epic. Definitely, it is music.

Those found texts became the seeds of a major work he called Barstow (Partch’s only extant solo recording of it is featured on Harry Partch, 1942). Soon he was aboard a freight train heading east to Chicago on the epic trip that would inspire U.S. Highball. (This 1958 performance filmed by Madeline Tourtelot, featuring Partch and footage from a California train, is delightful.)

By that point, Partch’s movements involved greater logistical planning. As Schneider observes in the liner notes for Harry Partch, 1942, the composer got ready for this trip by putting several of his new instruments (a Kithara, his take on an ancient Greek lute; and a Chromatic Organ console) into storage in Carmel, California. He hauled with him an Adapted Guitar and Adapted Viola, along with his sheet music and some clothes.

On the long freight rides toward Chicago, he kept up his notes. Some would show up in the vocals in U.S. Highball, subtitled A Musical Account of Slim’s Transcontinental Hobo Trip: “Going east, Mister?” “It’s the freights for you, boy.” “Let ‘er highball, engineer!” From Carmel, Slim heads through Nevada, crosses Great Salt Lake, and crosses Wyoming and Nebraska, switching between hitchhiking and the freights as he must. Leaving Rock Springs, Wyoming, another exchange: “There are lots of rides but they don’t stop much, do they, pal?” “Back to the freights for you, boy.”

In Chicago, he had lined up lodging with a friend of a friend. But covering expenses made for, as he wrote in a letter, “a precarious means of existence.” So he cobbled together dishwashing jobs and, in the summer of 1942, hitchhiked north of the city to join harvest work in the orchards and grain fields of Michigan, then worked in a lumber camp’s dining hall. Before long, he had musical gigs arranged in Chicago. One, Schneider notes, placed him on the bill with a young John Cage, a double-billing emblematic of the wide range of genres available to concertgoers then: Cage a formal experimentalist, Partch somewhere between unorthodoxy and traditionalism.

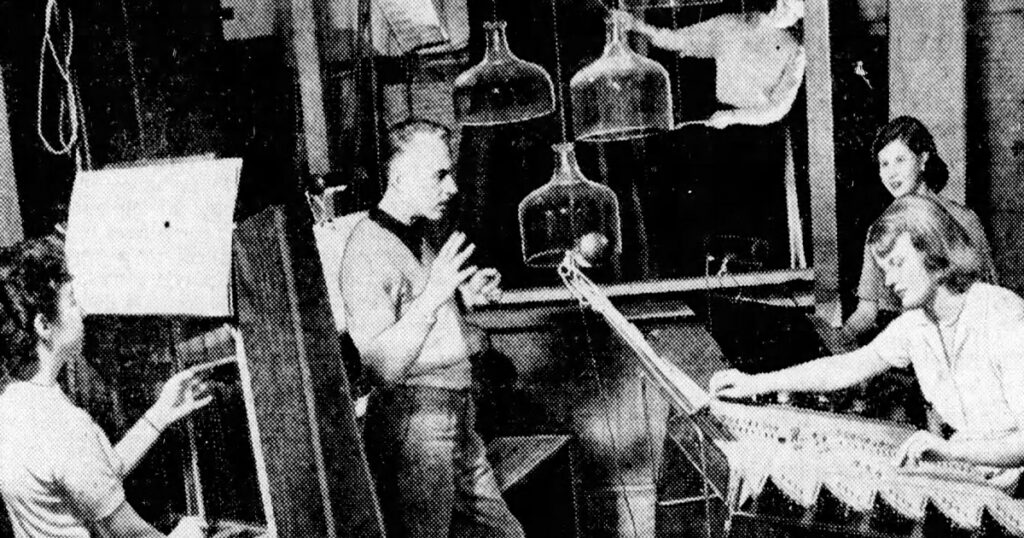

When Partch reached New York, he was feeling inspired and writing more. “I am working in a creative fever,” he wrote to his friend, the composer Otto Luening, “the most intense I have experienced in years—on ‘U.S. Highball.’” He submitted that project to the Guggenheim Foundation in hopes of getting their support. That winter, he moved around New England, meeting a range of American composers and creatives, including Martha Graham. With their encouragement, Partch assembled a handful of performers for a concert of his works with Chromelodeon (a pump organ redesigned to fit Partch’s tonal system), tin flutes, tin oboe, and a vocalist. They began rehearsals for a date in New York.

Partch eventually performed with the group at Carnegie Hall in April 1944. A review in The New York Times opened with a noticeable eye-roll: “What might be called the season’s most ‘sophisticated’ concert, or the most boring or the funniest, according to the point of view, was given late yesterday afternoon …” Still, the reviewer described the musical inventions with care, noting the performance was “said to be the first of the chromelodeon and the guitar in this city, and the first of the kithara anywhere.” And the reviewer did perceive Partch’s storytelling core, writing that the ideas and lyrics held center stage in an atmosphere shaped by the novel instrumentation.

A year earlier, the Times had published a piece by Woody Guthrie, fresh from releasing his memoir, Bound for Glory. He too wrote of listening to America as he bummed across the country. “I ain’t out to say that real honest classical music is better or worse than what you’d call folk music,” Guthrie wrote. “As far as ‘modern’ music goes, or folksongs either, there’s plenty of it that’s good and plenty that’s worse than useless.”

In Partch’s applications for funding, excerpted in Schneider’s liner notes, he walked the same line as Guthrie, writing, “I hold no wish for the obsolescence of the present widely heard instruments and music. My devotion to our musical heritage is great—and critical.” But to create “a healthy musical culture,” Partch wrote, “I am endeavoring to instill more ferment.” He and Guthrie were both churning in response to a conformist society, struggling to bring sidelined voices into a society that was largely uninterested.

Today, the 11-person Partch Ensemble in California, which Schneider leads, has continued the social and musical exploration of its namesake. Just before the pandemic put a pause on concerts, the ensemble performed “The Wayward,” which bundles four of Partch’s hobo compositions from 1941–43: Barstow, U.S. Highball, “The Letter” (told from the perspective of a fellow hobo), and “San Francisco.” Schneider played guitar and “as the main Woody Guthrie-esque hitchhiking composer,” wrote Mark Swed in his review for the Los Angeles Times.

Did time change the way we hear the tune? “I don’t know that anyone ever could get used to the sounds that Partch’s music makes,” Swed wrote. “The cloud chamber bowls ring like the tuned glass they are. The altered viola goes where no viola has ever dared. The bass marimba aims at a listener’s solar plexus.” Yet Swed ultimately found the work ebullient, leaving with a new feeling about the relationship between art and homelessness, and the dignity of the homeless.

In the end, Partch and Schneider’s Grammy bid got edged out by Chicago-based indie rock band Wilco. Partch’s liner notes are pretty long, too—a 72-page book containing photos is available for purchase. But Partch’s career may not be over yet. After all, Woody Guthrie’s first Grammy came in the form of a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2000, 33 years after his death. Harry Partch still has a shot.