Long-Distance Punishment

Could a landmark work of conceptual art be an emblem for the Covid era?

On July 24, 1970, John Baldessari took all the paintings in his possession—landscapes and abstractions that he had created between May 1953 and March 1966—to a San Diego mortuary, where he had them burned in its crematorium. Several art historians attributed this decision to Baldessari’s disillusionment with the state of painting, a frustration with the rigid formalist doctrine of modernist contemporary art. (“Baldessari began to reconsider not just painting but the practice of art-making itself,” one curator wrote on a gallery label at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.) Baldessari himself later said that his studio, a decommissioned California movie theater built by his father, was full of unsalable paintings. Hoping to change the direction of his art in a significant way, he felt it only logical to burn his earlier work.

“I thought about Nietzsche and the eternal return,” Baldessari told New Yorker art critic Calvin Tomkins in 2010, “and equating the artist with the ‘body’ of his work, and so forth. The problem was that several local mortuaries refused to cremate paintings. I found one finally, but the guy said we had to do it at night.” The event itself became a work of art, known as the Cremation Project, with photographs showing Baldessari at dusk, smoking a pipe and watching a gloved mortuary worker feed his work into a rectangle of fire. The ashes were subsequently baked into cookie-like figures that were placed in an urn and displayed.

When Charlotte Townsend-Gault of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design (NSCAD) in Halifax asked Baldessari to put on a show at the school’s Mezzanine Gallery not long after, she knew that the artist did not have any paintings left to exhibit. Instead, she wanted Baldessari to collaborate in the creation of a piece of art on site.

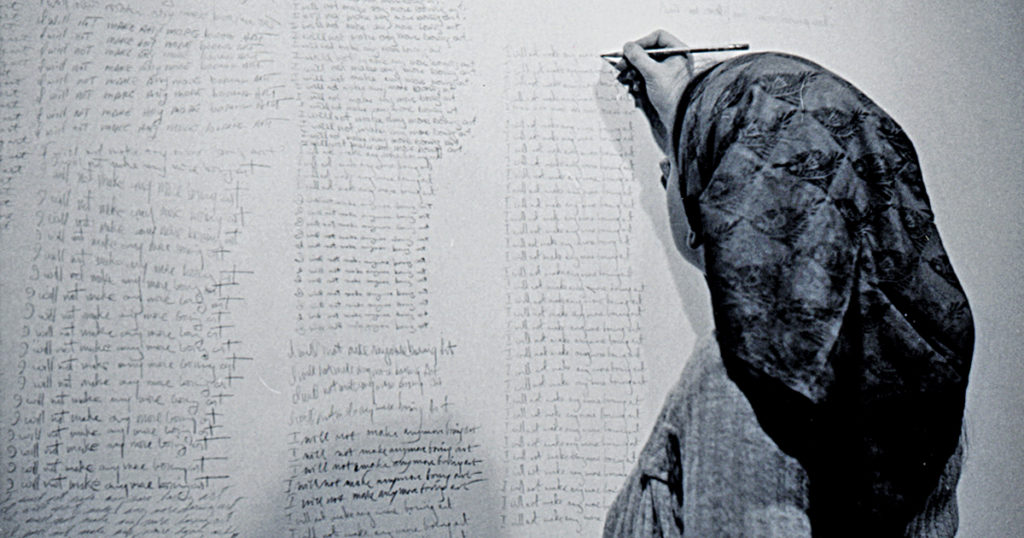

“I’ve got a Punishment Piece for you,” Baldessari wrote in response to Townsend-Gault’s request in February 1971. “It will require a surrogate(s) since I can’t be there to take my self-imposed punishment but that’s o.k. since the theory is that punishment should be instructive to others. … The piece is this: from ceiling to floor should be written by one or more people, one sentence under another the following statement: ‘I will not make any more boring art.’ ” In the envelope, he included a sample—he had handwritten the sentence—that was to be included on the mailed announcement of the show. The script tilts to the right; the slight variation of the length of each line creates a pleasingly unmeasured pattern.

Later that year, between April 1 and 10, NSCAD students carried out Baldessari’s vision, writing the sentence in pencil about 4,000 times, covering the walls of the Mezzanine from floor to ceiling. Black-and-white photographs from the show mostly depict students from behind, their hands lifted to the walls teeming with words. As Baldessari had made clear in his instructions, he did not believe that the students were actually deserving of punishment; rather, they would be the “holy innocents who will willingly take on my sins.” In the midst of creating the work, two of the students wrote Baldessari a letter describing the experience: “After the initial possible response of satire or witty solutions to punishment some people are still writing. It is a strange activity; there are a lot of columns of words on the wall.” They mention that the repetitive task was, indeed, despite the work’s title, boring.

The project was not without precedent. In the 1960s, Baldessari had hired professional sign painters to execute canvases for him. In this way, he was raising questions about the role of the artist and the very nature of artistic authority. During his 70-year career, Baldessari earned an international reputation as a seminal figure in conceptual art. His work is irreverent and funny, and the artist himself was playful; he made ironic art about art. He put text on canvas to describe what a painting should be. In one series of works, he used colored dots to obscure the faces of people in vintage photographs and movie stills.

Yet I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art remains the work for which Baldessari is best known. Following his death on January 2, 2020, numerous obituaries mentioned the piece—and, in doing so, printed his sentence thousands of times over.

Just after I finished graduate school, I moved into a brightly painted house in Charlottesville, Virginia, with three studio art students. I hung a poster of an Egon Schiele drawing in the stairwell and a reproduction of a René Magritte painting in my bedroom. Without comment on my taste, one of my housemates asked if I’d seen work by Cai Quo Qiang or John Baldessari. She showed me an image on her laptop of lifelike replicas of wolves posed together in the shape of a wave. She showed me a white canvas painted with the words pure beauty. I hadn’t realized that art could be so mischievous or shocking. I was entranced.

After Baldessari died, I read his obituaries, and I searched for images of his work and interviews. I rewatched A Brief History of John Baldessari, a 2012 short film that measured his acclaim in practical terms. (“John Baldessari is so successful that he carries absolutely nothing in his pockets.”) I indulged the impossible desire to close the distance between us, via the ephemera on the Internet, even after he had departed the world.

Months passed, and the pandemic winnowed my life. On a Tuesday, I took my laptop home from my office, where I edited a magazine for Canadian dentists, and I didn’t see my coworkers again after that. I read the news. I saw photographs and videos of people in socially distanced lineups, getting nasal swabs through open car windows, walking alone on once-bustling streets. But the only people I shared proximity with were members of my family. During those months, I was drawn back to Baldessari’s work, which felt free and risk taking, in favorable contrast with my own vigilant stasis. I was bored with panic and panicked with boredom. Baldessari’s work was delightful and droll. It buoyed me, too, that Baldessari believed that ideas matter, even silly ones.

But Baldessari’s work offered more than levity; it was evidence that art could be made at a distance. It was collaboration between people who never met “in real life,” before that phrase became current. It was art-making for Covid times, whose author had conveniently left the stage right before the lights went up.

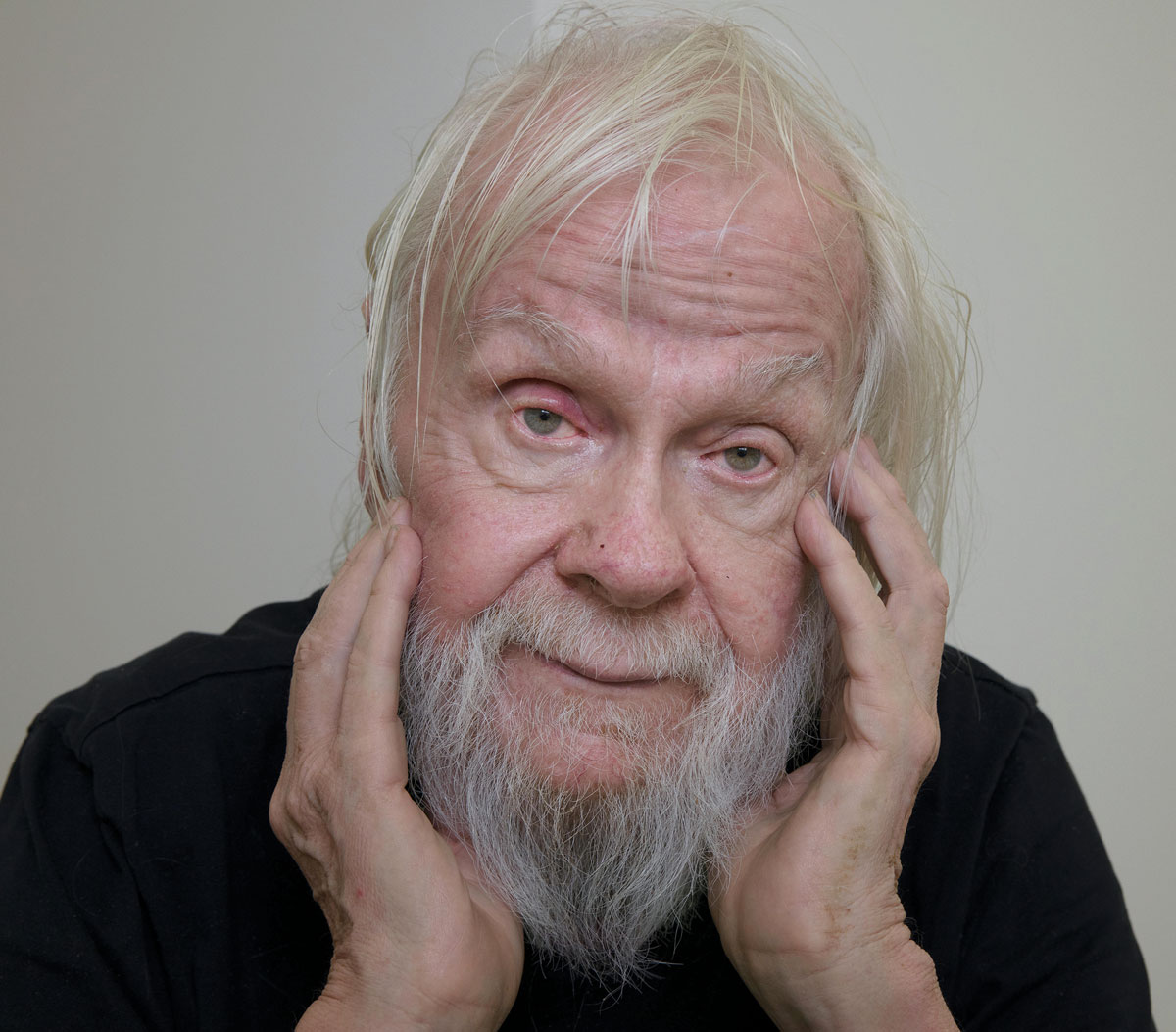

John Baldessari, shown here in October 2017, a little more than two years before his death (Dan Tuffs/Alamy)

In March 1971, before Baldessari’s punishment piece was performed at the NSCAD Mezzanine, Gerald Ferguson, an artist and faculty member who ran NSCAD’s Lithography Workshop, wrote to Baldessari to propose making 22-by-30-inch prints based on a photographic enlargement of the artist’s handwritten sample. Ferguson suggested a retail price of $100 each.

Baldessari’s I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art was printed in June of that year. “As an old hand at lithography, I had the enjoyment of printing this edition myself,” former NSCAD president Garry Neill Kennedy would write in his book about the college. “Baldessari’s penitential commitment to ‘not make any more boring art’ became emblematic of the College’s mission. It was a constant reminder of what we were about as a community of working artists.”

All 50 editions of the print were mailed to Baldessari to be signed. In the end, he sold half, and the workshop sold all the rest but one, partly to recoup the $500 cost of creating the print. The Museum of Modern Art in New York owns an edition of the lithograph. The Whitney Museum of American Art owns another. Edition 4/50 sold at auction in 2006 for $6,600. Edition 17/50 sold at auction in 2017 for $43,750.

After it was created in 1971, Baldessari’s famous sentence proliferated, in many iterations. Baldessari made a video art piece of himself writing the sentence over and over until the tape ran out, which took 13 minutes. That piece is owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The lithograph has been re-created as a silk scarf, about 1,500 of which have been sold. Baldessari also turned it into limited-edition wallpaper, and the phrase appeared on pencils and shopping bags. In 2010, the Whitney restaged the punishment piece. The Anna Leonowens Gallery at NSCAD also restaged it six years later, as part of a wider exhibition hosted by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia. The artists Teresa Hubbard and Alexander Birchler have an exhibition, Dear John, to be held at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in the fall of 2021, that will explore aspects of this work. I spoke to Hubbard about the two years of archival research on the punishment piece that she and Birchler have done. Until they began their research, no one had ever been interested in finding the people who first gave labor and form to Baldessari’s idea. “The central idea of our work,” Hubbard said, “has been to try to identify and locate all of the participants of the punishment piece as it was executed in 1971 and to conduct interviews with the surviving participants.”

When Calvin Tomkins and Baldessari watched the video version of I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art at the Met, the artist laughed. “And it’s very boring, isn’t it?” Baldessari said.

A few months after Baldessari’s death, I talked to Townsend-Gault about her commissioning the punishment piece. Speaking from Brussels via Zoom, she told me that it was unusual for Baldessari to separate the idea for a work of art from the labor of making it. “You know, he wasn’t Sol LeWitt,” she says, referring to the American artist whose conceptual art often consisted of a set of instructions that could be followed by others. (Indeed, one of my housemates created LeWitt’s Wall Drawing #394 at the University of Virginia’s Fralin Museum of Art while I was living with him in 2009, two years after LeWitt died.)

When I asked Townsend-Gault what it was like to be the curator of the Mezzanine Gallery, she disputed the words gallery and curator. The former, she told me, “carries all sorts of connotations, and none of them fitted what this place was trying to do.” The latter didn’t fit her position: “There was no name, no easy tag to give me. We all tried to work out better words for what I was doing and what the space was, but we never came up with anything that everybody could agree on. Which I sort of like, because it’s very hard to maintain an entity without an identity. We were trying to do something different. Many aspects of NSCAD, at the time, were aspirational. We tried to keep it indefinable.”

In those days, NSCAD often invited conceptual artists, such as LeWitt, Lawrence Weiner, Lucy Lippard, and Robert Barry, to submit projects that students could execute in class. Baldessari’s idea was a good fit with the Mezzanine’s indefinable ethos. “He got it,” Townsend-Gault said. “His piece was very evanescent, very short-lived. It was a little strange to look at. And it was hard to get people to do. I had to sort of chase people up. I ended up doing a lot of it myself.”

Baldessari did not attend the exhibition at the Mezzanine. Some accounts attribute his absence to a lack of funds needed to fly him from California to Halifax. But Townsend-Gault says that Baldessari’s absence was intentional. Her non-gallery was interested in creating art only at a distance, in ideas that could be transmitted for the cost of a stamp. “Conceptual art attempts to do something beyond definition,” she said. “It’s in the head. Conceptual art is only about the idea, right? Of course, there are masses of words written about it, but if you go to the works themselves, they’re almost pure. And this work of Baldessari is so puzzling perhaps because he’s using words about something that happens without words.”

During the pandemic, what I’ve missed most were shared experiences. I’ve longed to sit around a big table and share food, wine, and conversation with friends. I’ve wanted to hear live music among hundreds of fellow listeners, our bodies subject to the same sound waves and vibrations. Baldessari’s punishment piece was a shared experience over distance; writing the same words was the common activity that embodied the idea. The work of art was inseparable from the work that produced it, and the labor was shared between the artist in California and his surrogates in Nova Scotia.

I asked Townsend-Gault about the photographs I had seen of the punishment piece’s creation. I had noticed that there appeared to be only one woman in those images—we can see her headscarf, but only a sliver of her profile.

“That’s me,” she replied. “I could tell you all about that scarf.”

In a 1992 interview conducted for the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian, Christopher Knight asked Baldessari what he considered his most significant piece of work. “Well, I don’t know about recently. It’s hindsight. I mean, the more distance you have, the more things fade in your memory,” Baldessari said. “But two pieces had always seemed to me to be watershed works for myself—or pivotal or seminal or whatever.” Neither of the pieces he mentioned was I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art. Instead, he talked about the all-text canvas Semi-Close-Up of Girl by Geranium (Soft View) from 1966–68. He also mentioned Concerning Diachronic/Synchronic Time: Above, On, Under (with Mermaid), which he made in 1976. It consists of found black-and-white images, arranged in a two-by-three grid in a way that suggests likeness as well as simultaneity. The top two images depict an airplane in the sky and a bird aloft. The middle two are images of ocean horizons. The bottom two show divers in an undersea vehicle and a swimming mermaid. The piece is a koan, a trick question to tickle the mind, a short meditation on time and distance.

“You know how you get that while something is happening here, something is also happening over there?” Baldessari said about the piece.

It’s impossible to keep all those things in your mind, but one should try to do it. And I think that’s maybe a reason that quite often my work looks, the parts look so disparate, but I’m trying to convince myself that while this is happening, this is also happening, and this is also happening, and they’re related in my mind in some way, which I could describe, but I think [that sometimes] drives … other people a bit crazy.

There is a unity in this idea that each of us is in our separate space but linked by our existence at the same time. Everyone is connected—by shared work, related ideas, and happenstance—despite distance. In the spring of 1971, Baldessari was teaching a class on the grounds of the Villa Cabrini, a former Catholic girls’ school in Burbank that served as the temporary campus for the California Institute of the Arts. Meanwhile Townsend-Gault, wearing a scarf over her hair and annoyed that she couldn’t persuade more students to help her, was writing in pencil on the walls of a small annex in a Canadian city next to the Atlantic Ocean.

This morning, I woke up before my children did and drank coffee at the kitchen table with my husband as rain splashed against the windows. I couldn’t find a pencil, so I picked up a red pen and wrote Baldessari’s famous lines in a notebook. The scratch of pen against paper made a regular rhythm. My hand made the same movements that Baldessari’s had 49 years ago, and also the same as Townsend-Gault’s, as if we’d learned the same dance. I thought about exciting art, ideas that made reality look different, changed by a shift in perception. I thought about connecting with both Baldessari and Townsend-Gault across not only space but time. Then I got bored. Being bored, it turns out, is another way of being together.