Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit; Viking, 320 pp., $28

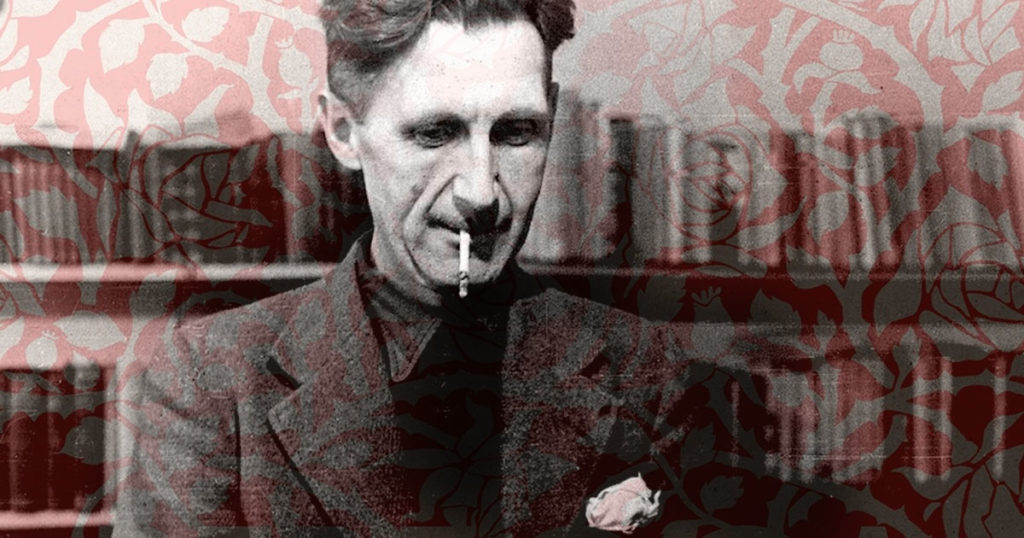

Hertfordshire, England, 1936. A young writer, newly wed, rents a ramshackle cottage from his aunt. He should be finishing a book on industrial poverty, but instead he buys rosebushes at the local Woolworth’s to brighten his aunt’s flowerbed and shovels them in himself. “Outside my work the thing I most care about is gardening,” he later confesses. His life will be short (1903–1950), but nearly everywhere he lives, he plants. In the privacy of his many gardens, he is Eric Blair, Eton graduate, who counts an earl and a slaveholder among his ancestors. On the page, we know him as Orwell, George Orwell.

In Orwell’s Roses, a sheaf of essays and short takes on horticulture and power, Rebecca Solnit reminds us that the inventor of Big Brother and coiner of the term cold war was also a lifelong outdoorsman and gardening fiend, who took his pen name from a Suffolk estuary he loved, the River Orwell. This is no biography, she warns early on, but a series of intellectual forays inspired by Orwell’s gesture, and “also a book about roses, as a member of the plant kingdom and as a particular kind of flower around which a vast edifice of human responses has arisen, from poetry to commercial industry … Roses mean everything, which skates close to meaning nothing.”

Fair warning. To enjoy these off-road trips, it’s best to cease hunting for point, direction, and shape, as Eudora Welty said of Annie Dillard’s Pilgrim at Tinker Creek (1974), and surrender instead to Solnit’s iron insistence on sidestep and meander, a way of writing she calls rhizomatic, in homage to the decentralized root networks employed by plants like iris or bamboo in order to spread and conquer.

Some of these sorties feel like notes for magazine pieces that never cohered; others start big, then skitter and evaporate. But the book teems with people (and plants) behaving badly, and Solnit is an inspired guide to the byways of botany, notably Stalin’s dogged attempts at lemon control, the allure of floral chintz, the politics of enclosure, and the Western garden as imperial palimpsest. Pocket biographies of rose-touched lives pop up to fine effect, from Soviet science czar Trofim Lysenko to charismatic photographer and revolutionary Tina Modotti, who blazes across the page like a Crimson Glory in full bloom.

Orwell’s Roses shares literary DNA with several strains of nonfiction, including the commodity-book-as-cultural-peephole—such as Mark Kurlansky’s The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell (2006) and Betty Fussell’s The Story of Corn (1992)—and the obsessive compendium, like Charles Sprawson’s Haunts of the Black Masseur (1992), created to justify (or exorcise) a lifelong fascination with some topic: for Sprawson, swimming, for Solnit, apparently, Orwell.

Like her quarry, Solnit is a public intellectual and activist who writes best when angry, and her career as social critic includes some excellent philippics, most famously a withering 2014 essay on gendered cluelessness, Men Explain Things to Me. This book could have used more fury. An eyewitness account of Colombia’s rose industry, for example, describes only a genteel show factory, not the notorious sweatshop operations supplying First World markets from equatorial nations worldwide. But Solnit’s conclusion is nevertheless hard to unsee:

Each box, they told us, holds 330 roses, and one 747 can hold 5,000 boxes, or 1.65 million roses. The idea of an immense airplane whose sole freight was roses burning its carbon and rushing high over the Caribbean to deliver its burden to people who would never know of all that lay behind the roses they picked up in the supermarket was maybe as perfect an emblem of alienation as you could find. Could roses be more uprooted?

Solnit’s taste for the horizontal and nonhierarchical favors surprise connections, unexpected echos, odd foretellings. But Orwell is a diver, a digger, Solnit a natural skimmer, and the strain is never resolved. For instance, the scholarly literature on Orwell out-of-doors is ample, absorbing, established—and absent from her sourcing. AWOL, too, is any sustained discussion of the immense cultural weight given roses on the Continent, in the Middle East, across Asia and, profoundly, in the United Kingdom. Rhizomes are, by definition, shallow. Roses have none. Rather, they have anchor roots, that plunge and grip, deep into history, as Orwell knew. Solnit’s bouquet, delightfully varied, can seem hydroponic, a conjurer’s flower.

Orwell’s Roses could also have used more Orwell. Too often he functions here as mascot or touchstone. When allowed onstage, the book snaps into focus. His tonic clarity braces Solnit’s talent for waffle, which in helpings this large can be doubleplusungood, and in their dialogue across the decades we glimpse the book that might have been.

For when Solnit abandons meta-collage for close reading, the results are remarkable. In our earth-conscious age, she contends, grim, gaunt, wintry Orwell can also be an avatar of growth and hope. The hero of 1984 yearns, after all, for a sunlit Golden Country of meadow and stream, the kind of landscape that haunted Orwell lifelong. Solnit’s eco-reading does not dead-end in terrifying Room 101 but restores nature and women as counterbalances to power in a dream-rich novel of “vitality and generosity and fecundity.” Acts of resistance come in many forms, she reminds us, like pleasure, like beauty.

As his good friend Cyril Connolly wrote, the month Orwell died, “It is closing time in the gardens of the West and from now on an artist will be judged only by the resonance of his solitude or the quality of his despair.”

Orwell’s Roses would not make the man despair; far from it. But he might be wary. That opening anecdote of visiting the Hertfordshire cottage to discover his lost roses blossoming still, one pale pink, the other salmon rimmed in gold, forever England, would touch the hardest heart. Yet deeper in the text we find this throwaway line, “It is not absolutely certain that the two rosebushes growing there now are those he planted.”

Ah. Proceed with caution. 2+2=5. It’s that kind of book.