On October 28, 1964, when I was 26 years old and in my first semester as an instructor in Columbia University’s English Department, my father called and asked if I’d read an article in The New York Times that morning about I. I. Rabi. I had not. “Well go and read it,” my father said, “because I. I. Rabi teaches at Columbia, and was born in the shtetl of Rymanow, which is where my parents—your grandparents!—and my six older brothers and sisters were born, so call him and tell him you come from the same shtetl—that you’re landsmen!”

I protested that Professor Rabi was a Nobel Prize–winning physicist, and I was just a part-time instructor, but my father would have none of it. “You both went to Columbia,” he said, “and you both teach there, and he was born in Rymanow—where our family comes from—so I don’t see why you can’t call and get together with him.”

My father was a mild-mannered man who rarely insisted on anything. He had failed at several businesses, and it was my mother, a registered nurse, who—to my father’s embarrassment—had always supported our family. I was surprised by his call, and more surprised when he called the next day to urge me once again to contact Professor Rabi, and to express his disappointment in me for not doing what he’d asked.

So I wrote a letter to Professor Rabi on English Department stationery, telling him what my father had learned, and that he’d encouraged me to get in touch.

A few days later, while I was holding afternoon office hours, my phone rang.

“Mister Noy-geboren?” a man said, pronouncing my name in the German fashion.

When I said that it was, the man spoke with a more familiar Brooklyn accent. “Listen,” he said. “This is Izzy Rabi. I got your letter. You wanna have lunch?”

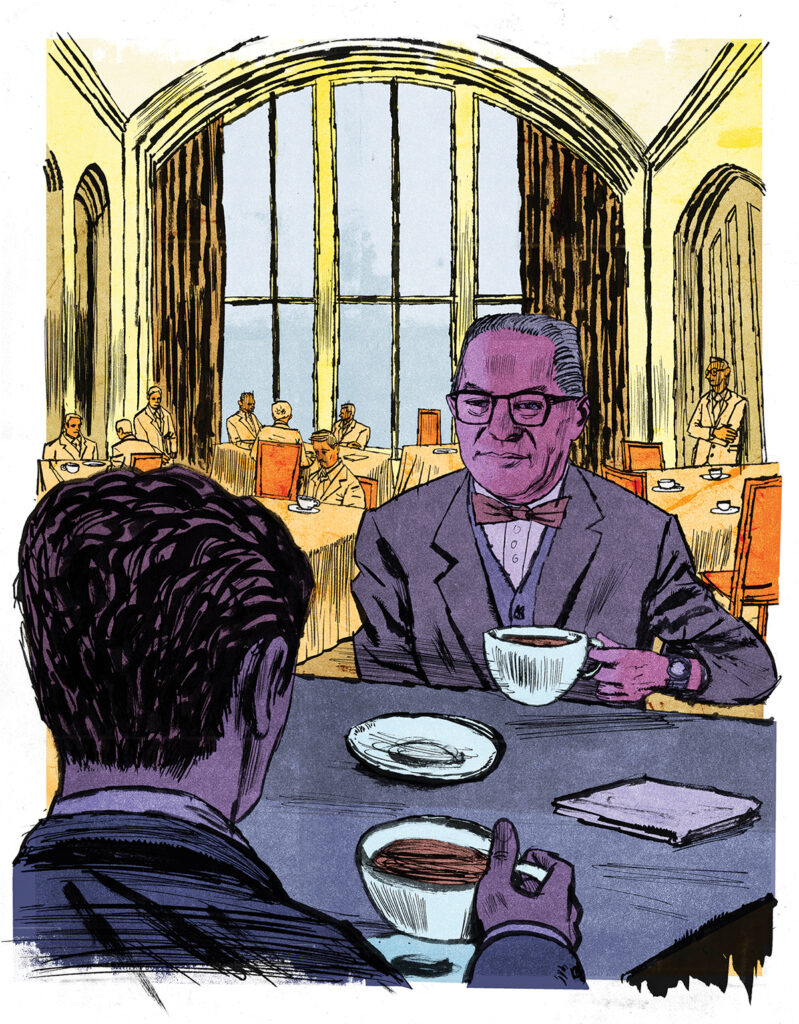

And so, a few days later, I met Isidor Isaac Rabi for lunch at the Columbia University Faculty Club, where he told me to drop the “professor stuff” and call him “Izzy.” He said he’d left the Polish town of Rymanow before he was two years old and didn’t know much about it, other than that it was the home of Menachem Mendel, the red-bearded rebbe about whom Martin Buber wrote in Tales of the Hasidim. As soon as we were seated, he commented on my unusual family name (Neugeboren means “newly born”), and how I looked “very Neu-geboren”—like an undergraduate—and he asked me to tell him about myself and my family.

I said that my father was the second youngest of nine children from an Orthodox Jewish family, and when the family came to America, they’d lived on the Lower East Side before moving to Brooklyn. Professor Rabi said that, like my father, he’d grown up in an Orthodox Jewish family and had lived on the Lower East Side before moving to Brooklyn, and that we’d talk about our families later, but what he wanted to know now was how such a young man had wound up teaching at Columbia.

I told him that, like him, I’d gone to Columbia and that although I was technically a doctoral candidate, a status that allowed me to teach freshman English, I never went to classes and had no intention of completing my Ph.D. because what I wanted to be was not an academic who wrote about literature but a novelist who wrote the literature other people wrote about.

He hesitated—had I revealed too much too soon?— then leaned back and smiled brightly. “A novelist—how wonderful!” he declared. “But tell me more, because in my line of work—the sciences—it’s the same as in your line of work: you need the basics, of course—how to run a lab test or produce a good sentence—but what makes the difference is imagination!”

I exhaled, and when he invited me to tell him more about my writing, I said that I’d written seven unpublished books, to which he replied by saying that when he was a boy, the public library was his second home, and he’d read through all the books on the children’s shelves before ever looking at a book about science—that he’d “knocked around” for a long time before settling on physics, had analyzed furniture polish and milk in his first job, and assumed we all had to serve apprenticeships.

He then asked what I thought of President Eisenhower, who had served as president of Columbia (from 1948 to 1953) before becoming president of the United States. He asked the question, he said, because people at Columbia had greatly underestimated what a terrific president Eisenhower was. When the university hired him, the standard joke among faculty was that the trustees had called “the wrong Eisenhower”—that they had meant to call Milton Eisenhower, Dwight’s brother, who was president of Penn State. But Eisenhower, Professor Rabi said, was a great president who understood the necessity of having the sciences and humanities communicate with each other, and he wasn’t talking about building bridges between them, I recall his saying, but of having them interpenetrate, so that laymen wouldn’t feel alienated from science, and scientists wouldn’t wall themselves off from the arts.

While we ate, we talked easily—about our families (his father and mine were both named David), about Brooklyn (he’d gone to Manual Training High School, the arch rival of my high school, Erasmus), about novels and novelists (he was good friends with Herman Wouk), about our public school educations (physics had been one of my favorite high school subjects), and about being raised in observant Jewish families. We discovered that although we both identified proudly as Jewish, were knowledgeable about Jewish history and culture, and valued the moral teachings of Judaism, neither of us believed in God, or held to any beliefs about prayer or ritual.

After we’d talked for a while about Jewish artists and scientists—about Albert Einstein and Sigmund Freud, Saul Bellow and Bernard Malamud, George Gershwin and Yehudi Menuhin—he suddenly leaned across the table and, in a whisper, asked why I thought it was that despite centuries of persecution, Jews had excelled out of all proportion to our minuscule fraction of the world’s population.

“Survival of the fittest,” he said quickly in answer to his own question, and when I didn’t immediately agree with him, he said that one couldn’t say what he’d just said too loudly—that of course he didn’t believe Jews were genetically smarter than any other group of people, but because of the persecution we’d suffered, we’d honed what talents and brains we were given to finer points than we might otherwise have done. It was, he said, simple Mendelian arithmetic: Those within the Jewish community who were healthier, stronger, or more clever—or more useful to the rulers of nations we’d lived in because of particular talents—survived in larger number.

I protested, citing the millions of poor, uneducated Eastern European Jews who’d come to America without exceptional skills, yet had brought into being several generations of Jewish Americans who had excelled in remarkable ways. And what about luck? I asked. My points were well-taken, he said, and he quoted Louis Pasteur about chance favoring the prepared mind, and this led him to suggest another element that accounted for our achievements: that we’d always been a nomadic people with a history of being expelled from country after country, and thus had come to value things intangible—reading and study above all—that prepared us for the arrival of good fortune if and when it came, and that this was so because, unlike physical objects and property, our knowledge—what we read, studied, and thought—was transportable and could not be taken from us. “We’re not known as the people of the book for nothing,” he said.

As soon as I arrived home, I called my father and told him all about my afternoon with Professor Rabi. I said that, to my surprise, the lunch had gone on for nearly four hours, and that I’d felt so comfortable with him that I was able to disagree with him on certain points.

“See?” my father said. “There was no reason to hesitate or be nervous—he’s our landsman.”

All of this came to mind late last year when I saw the movie Oppenheimer, in which Rabi is played by David Krumholtz. I recalled how my father, who was often critical of me and rarely insisted on anything other than that I “be good to Mother,” would—uncharacteristically for such a shy, often withdrawn man—ask me to tell others about my lunch with I. I. Rabi. He was proud in those moments, almost bragging. And it occurred to me for the first time that he was proud not only that I had spent an afternoon with I. I. Rabi, but that I. I. Rabi had been fortunate to have spent an afternoon with me.