Lynn Boggess was born and raised in West Virginia, and continues to live in the south-central part of the state—on a 120-acre property, where he paints en-plein-air. Here, he discusses his artistic influences, why he decided to paint landscape in a hybridized style, and what he loves about the natural beauty of his home.

“When I got to middle school, I discovered the work of Andrew Wyeth. That kind of galvanized my desire to become an artist. He used the same sort of subjects I was encountering, growing up outside of town on farmland. He depicted vacant spaces punctuated with architecture, which generated a great deal of interest for me, especially his watercolor paintings. I didn’t associate with his egg tempera works—they were too tight. But his watercolors were spontaneous and real, and had a gestural quality that I gravitated toward.

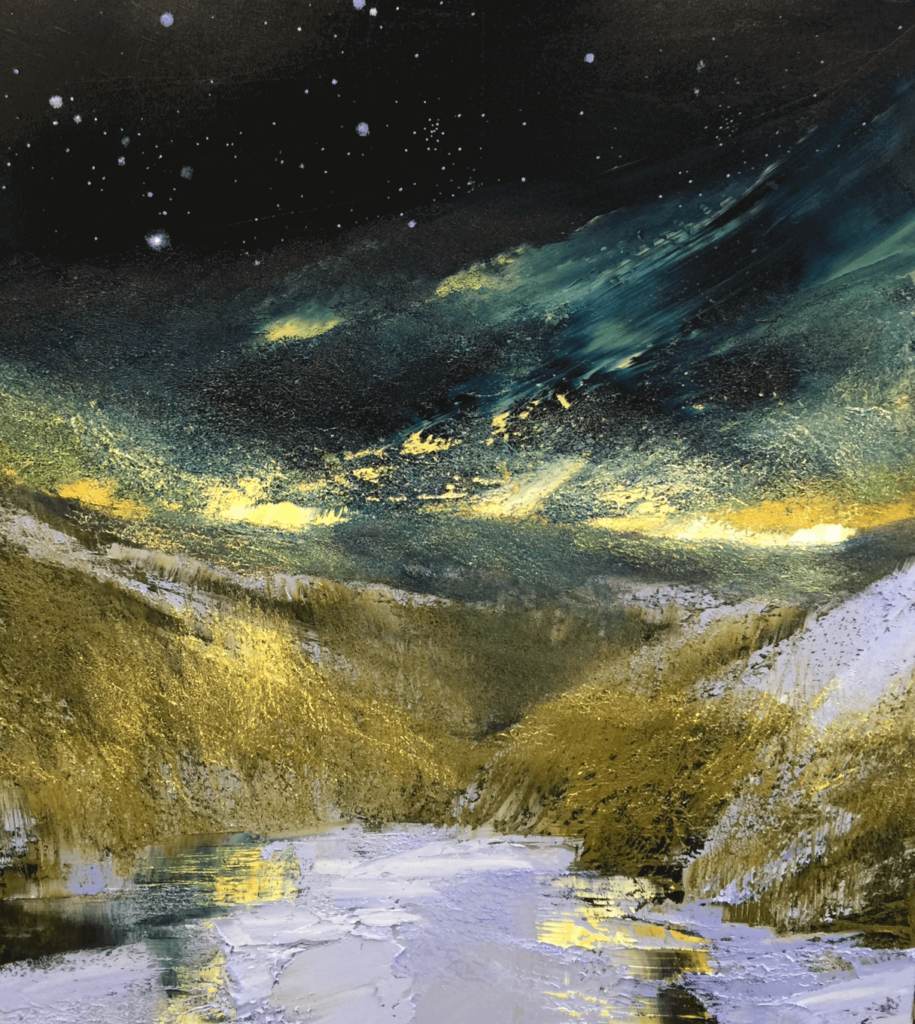

Landscape painting is all about composition. My style takes two radical schools of thought and tries to marry them. I started off utilizing a Gerhard Richter–type technique, which was a lot of smear painting. But I also try to match what I paint to what I see, so I work within the realist tradition, as well. Beyond that, though, I inject what I feel about what I’m looking at—as opposed to empirically what I’m looking at—onto the surface of the canvas. One day, I took a trowel along with me, and my approach to painting changed. I worked for two minutes with that thing. The tactile quality—I wanted to respond not just to the light and color of the scene but also to the feel of it. From the feeling, that’s where you get the abstract expressionists’ whole thing about putting something down with a gestural thrust to it. The trowel allows you to do that. It has a force or a sublime quality to it. Oil paint is thick, and the medium is the message. I was never able to tap into that with a brush. With a trowel, you don’t have to add anything to the paint; you can mold it and shape it like a relief sculpture. If you’re going to make a landscape painting, you have to tune into the tactile. You have to pay attention to the glassiness of water, the ruggedness of bark, the grittiness of sand or rock. The tactile puts a human being in the presence of something else.

When I’m deciding what to paint, three things have to match up for me: the season, what’s happening with the weather, and my mood. If I’m feeling heroic, I’ll pick a rugged and vertical landscape to tackle. If I’m despondent, I’ll pick a scene that’s horizontal and more relaxing. My property has everything on it that I need. It has ridgelines, huge rocks, still water, moving water, every kind of tree you could think of, and it’s colorful all year round—even in the winter, it has luscious greens and blues. Everywhere you turn, there’s a painting. West Virginia is a rural state. The population is concentrated in only a few areas, and there’s a lot of wide-open wilderness. For someone with transcendence on his mind, it’s a perfect place. It’s raw and accessible, inviting you to be outdoors. The state has a character about it, a kind of terrible beauty.”