Man of the World

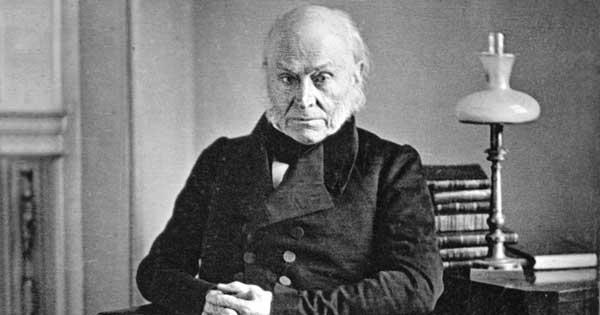

Well-traveled and erudite, John Quincy Adams sometimes had trouble appealing to his countrymen

John Quincy Adams: American Visionary, By Fred Kaplan, Harper, 652 pp., $29.99

Few if any men were ever better qualified, at least on paper, to serve as president of the United States than John Quincy Adams. A diplomat several times over, lawyer, senator, and secretary of state, he had grown up in a household with parents who had been center stage at the creation of the American union. By example and exhortation, John and Abigail Adams instilled in their precocious and talented son a deep faith in, and enthusiasm for, the American experiment. Significantly, from an early age, John Quincy saw the beginnings of the country from both inside and outside its borders. When the Continental Congress sent John Adams to Paris to replace Silas Deane on a joint commission that included Benjamin Franklin and Arthur Lee, the Adamses decided that their 10-year-old—the eldest son of their five children—would go along. As Fred Kaplan writes in this insightful and engrossing biography of our sixth president, “Europe would be his school.”

And what an education it was, both in the classroom and outside it! Spending his formative years in a Francophone country set young John Quincy apart from other Americans in ways that were wonderful for his personal development. He became fluent in several languages and was, perhaps, our most erudite president. But the experience likely contributed to the difficulty he faced later in life when attempting to appeal to the masses of his fellow citizens. It was not just that Adams spent time in France. He traveled extensively throughout Europe during his seven years there. Four years into his European stint, his father gave him permission to travel to St. Petersburg, Russia, with Francis Dana, who had been appointed as an emissary to the court of Catherine the Great. John Quincy, already fluent in French, would serve as Dana’s personal secretary: heady stuff, indeed, for a 14-year-old. In all, young Adams traveled to seven European countries, making him in his father’s words, “the greatest Traveller, of his age.”

But he was much more than just a traveler. As Kaplan makes plain in his own clear and finely chiseled prose, John Quincy Adams was, at his core, a writer. In addition to the documents created for his work as a public servant, he produced an astounding array of private papers. He kept a diary and wrote thousands of letters and wide-ranging pieces of literary criticism. He also wrote poetry, mostly for his own enjoyment, but at times deployed it as a political weapon, penning anonymous attacks on Thomas Jefferson, with whom he had a complicated relationship. Adams began as a young admirer of Jefferson’s but eventually grew impatient with the elusive third president, whom he saw as “living in a world of fabrications, many of which [he] believed to be absolute truths.”

As for literature, Adams considered it “the charm of my life, and could I have carved out my own fortunes, to literature would my whole life have been devoted. I have been a lawyer for bread, and a Statesman at the call of my Country.” His mother Abigail, his first teacher, taught him to recite verses that he later described as “beautiful effusions of patriotism and poetry.” From that base, he grew to love words, reading them and writing them in copious amounts—a fact reflected in Kaplan’s work, which is as much a literary biography as a political one.

Adams’s diary, an enormous aid to Kaplan, shows him to have been the product of his upbringing by exacting New England parents despite his turn in Europe. “John and Abigail believed that children were brought into the world to be taught moral rectitude. Parents owed their children admonition and discipline, not expressive sentiment.” Rectitude Adams had in abundance. And his sense of his own rightness, a valuable personal compass, was not attractive to the larger masses of the people who had the vote when Adams decided to stand for election to the presidency.

Unfortunately for Adams, he contended for the office at a time when a candidate’s credentials mattered less to voters than their perception of his character. Or one should say that the definition of credentials did not encompass the kind of experience that Adams brought to the table. His erudition and worldliness did not play well with a populace standing on the edge of the age of the “common man,” wary of elites and determined not to be ruled by men who, in any way, signaled that they thought they were above “the people.”

As the subtitle of Kaplan’s book, American Visionary, suggests, Adams had an abiding faith in the American union and believed the purpose of the presidency was to help knit the nation together through a commitment to progress. Indeed, Adams’s first message to Congress detailed that vision. The national government would build roads, bridges, and canals. It would help fund a national university and a naval academy and underwrite scientific endeavors like the exploration of the Pacific and the construction of an astronomical observatory. The purpose of government was “for the improvement of the condition of those who are parties to the social compact.” The nation would move together on this project, he said; otherwise, what was the purpose of its union?

Adams’s vision was not shared by large numbers of Americans, nor would it be today. And one wonders how this broadly educated man with a writer’s soul, who could speak and think in foreign languages, would play in contemporary America. Like his father, John Quincy served only one term as president. He barely made it to the office at all. Although he lost the popular vote to the victor of the Battle of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson (about whom Kaplan is justifiably merciless), he attained the presidency by a decision of the House of Representatives. Then, when he sought reelection in 1828, he was engulfed in a wave of Jacksonian populism, from which the country has only fitfully recovered.

If Adams is known today, it is largely by his postpresidency career in the House of Representatives, where he became known as Old Man Eloquent, particularly for his stance against slavery. Adams’s views on race were as execrable as those of most whites of the day, but he was firm in his belief that slavery was a moral wrong and feared, rightly, that it would be “the rock against which the ship of state would be split apart.” No doubt most current-day Americans know him through his participation in the Amistad case, made famous by Steven Spielberg. Adams fought the good fight and gave his all, collapsing on the floor of the House and dying in one of its chambers.

The memory of John Quincy Adams deserves our attention, and Kaplan’s book does much to rescue him from oblivion. Adams was not, as historians have sometimes regarded him, merely a speed bump on the road to the Age of Jackson. One cannot read Kaplan’s fine biography without thinking of our own times. The debate over Adams’s vision of the role of government rages on as we continue to ask, in one way or another, what is the purpose of our union?